Previous Episodes

- June 2025

- May 2025

- April 2025

- March 2025

- February 2025

- January 2025

- December 2024

- November 2024

- October 2024

- September 2024

- August 2024

- July 2024

- June 2024

- May 2024

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

Three Stories…

This episode focuses on three stories in the Nihon Shoki—fantastical stories about ghosts, shapeshifting bandits, and the famous Rip van WInkle of Japan: Urashima Tarō.

The write-up here is going to be pretty short, but we hope that you enjoy these more lighthearted tales. I’m sure I’m not the only one who could use a distraction given everything going on as this comes out at the start of March, 2022.

-

Welcome to Sengoku Daimyo’s Chronicles of Japan. My name is Joshua and this is Episode 59: Urashima Taro and other stories.

First, thanks to Lauren for supporting us over on Ko-Fi.com, and a belated thanks to Gaijin Historian for supporting us on Patreon. If you would like to join them, go check out SengokuDaimyo on either platform, or see the links on our own home page at SengokuDaimyo.com.

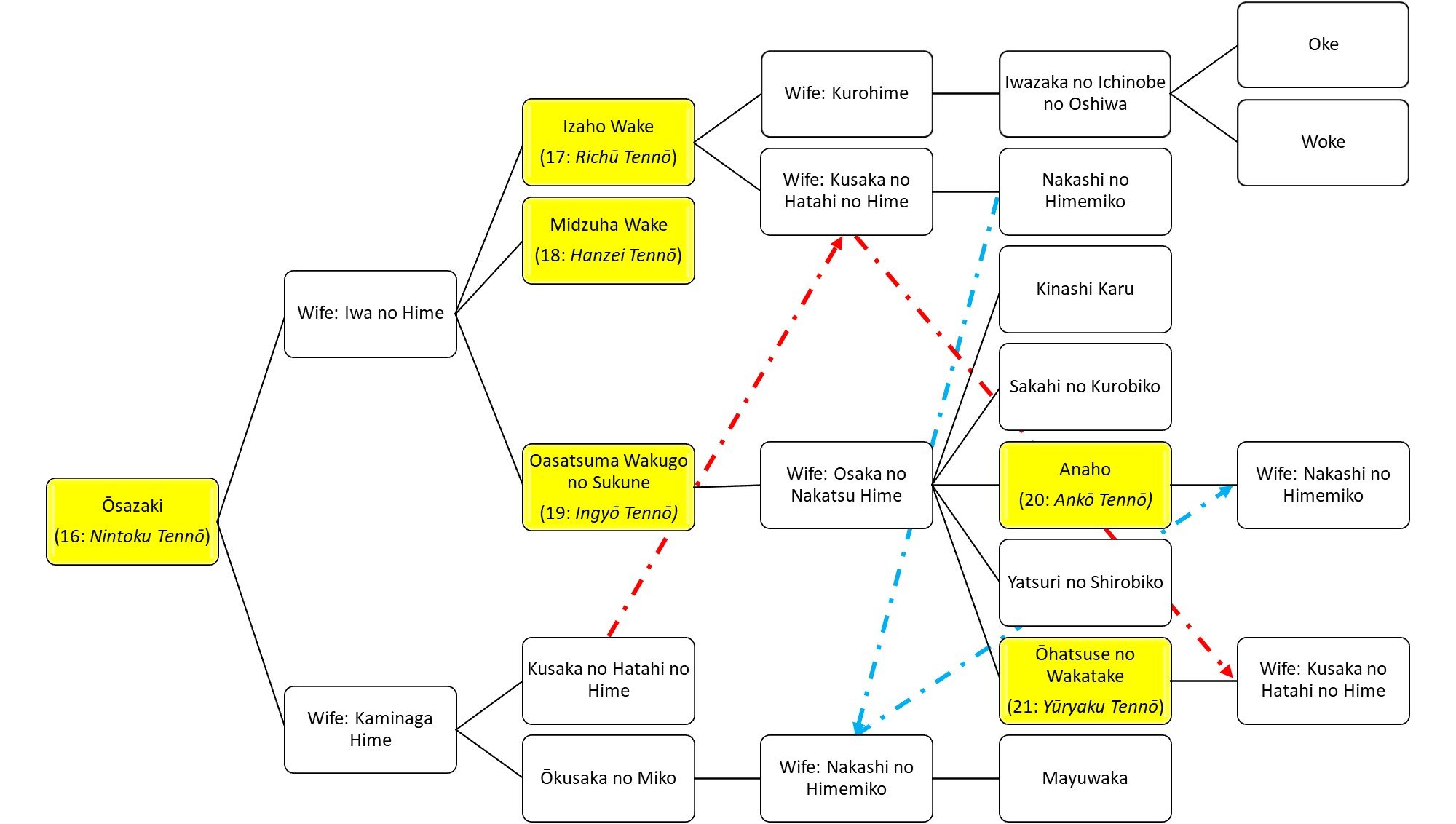

With that out of the way, a quick apology: this episode is a little short. I had intended to jump into the life of our current sovereign, Ohohatsuse, aka Yuryaku Tenno, but there is still a lot of information I’m trying to get through, and I’d rather make sure that I have as much as I can before I start jumping into all of that, because it is a lot. But I don’t want to leave you hanging, and there are a few fun stories that don’t really impact the overall story, so I thought I would pull on those.

To be honest, these stories would probably fit better in a Halloween episode. They are full of ghosts and werewolves and fantastical stories—and some of them you may even know. They hearken back to some of the stories we’ve already heard: from the isle of the immortals to stories about the great Homuda Wake, aka Oujin Tennou, and I think they also help tell us a few things as well.

For one thing, it is interesting that they exist at all. For the most part the Nihon Shoki was compiled as a dynastic history, telling the story of the royal family. Rarely do we get glimpses of others unless they are directly involved, somehow, in the royal lineage. Most of the time the stories of the fantastical are built around the stories of the sovereigns themselves—and certainly we have those stories in this period, too.

Of course, stories of ghosts and magic can’t exactly be taken at face value, and it does make us wonder about the rest of the narrative. We can’t even be sure that these stories are set in the proper time. Were these stories that were being told in the 5th century? Or did they come about later, and just get added in here? Certainly some of the stories of continental exploits seem like they may actually be more appropriately attributed to an earlier sovereign, so while we can probably start to make some assumptions as to the accuracy of some dates, other events may have simply been placed in the time that seemed to best suit the lesson that was being communicated. Either way, we can’t necessarily claim that these are actual fifth century stories—what we really know is that they existed by the eighth century and were well-known enough to have been written down in the compilation that became the Nihon Shoki.

The three stories I want to focus on each deal with slightly different themes and events. To start with, perhaps it may be best to talk about the ghostly horse from the tomb of Homuda Wake, aka Oujin Tennou. As you may recall, his reign was credited with the arrival of the first horses from the Korean peninsula, along with their keeper, Ajikki.

Next, we’ll dive into something of a werewolf story. Well, kind of—it may not exactly be a Lon Chaney style story, but there is definitely the idea of fantastical shapeshifting, which is almost its own genre in traditional Japanese stories.

Finally, we’ll touch on what I suspect is the most famous of the stories—perhaps one of the most famous stories in Japan. That is the story of Urashima Taro, or, as he is known in these early stories, Urashima-ko, the Child of Urashima. This is Japan’s own Rip van Winkle story, and it also shares a fair amount with some of the earlier stories of the Nihon Shoki, during the legends of the very first heavenly descendants. This early version also relies on the use of the famous Peng Lai, or Isle of Immortals, from stories of the famous Qin dynasty.

All of that, and perhaps a little bit more, in this episode. Let’s get into it, shall we?

Our first story in today’s triple feature comes, we are told, from the reports from the Kawachi area as recorded in the Nihon Shoki. If the Chronicles are to be believed, one of the earliest purposes for writing in the archipelago was to collect information from around the countryside and relay it back to the central government. Reports like this—the later fudoki—often give us intriguing insights into life outside the center, and can be quite illuminating.

The report from Kawachi tells of a man in Asukabe named Hakuson of the Tanabe no Fubito. Hakuson—and that name is odd, as it doesn’t look like a Japanese name, but I’ll touch on that later. Anyway, Hakuson had a daughter, and she was married to a man named Karyu of the Fumi no Obito. Together, they lived over in Furuichi, just a short distance away, across the Ishi River.

Anyway, as he was on his way home that night, the moon shining bright in the night sky, he was passing by Ichihiko Hill—better known as the tumulus of Homuda Wake, the great-grandfather of our current sovereign. As he passed the giant mound, he saw a rider mounted on a red courser, which was dashing along light a dragon in flight. Hakuson became envious of such a horse, and he whipped his own piebald horse into a gallop and brought him along side, until they were riding bit to bit. But then the red courser sped up, like a little Nash Rambler to Hakuson’s Cadillac. Pretty soon, Hakuson realized there was no way that he’d be able to catch up, and he was about to give up, when the other rider slowed and turned back around.

He realized that Hakuson had been coveting his ride, and the stranger agreed to swap horses with him. Hakuson was overjoyed and couldn’t believe his luck. He thanked the stranger, and then he quickly made his way back home, in Asukabe. There he tied his new horse up in the stables and went to sleep.

The next morning, Hakuson woke, no doubt with a spring in his step. He had never seen a horse like the one from the previous night, and now it was his. He went straight to the stables to take in his newly acquired equine.

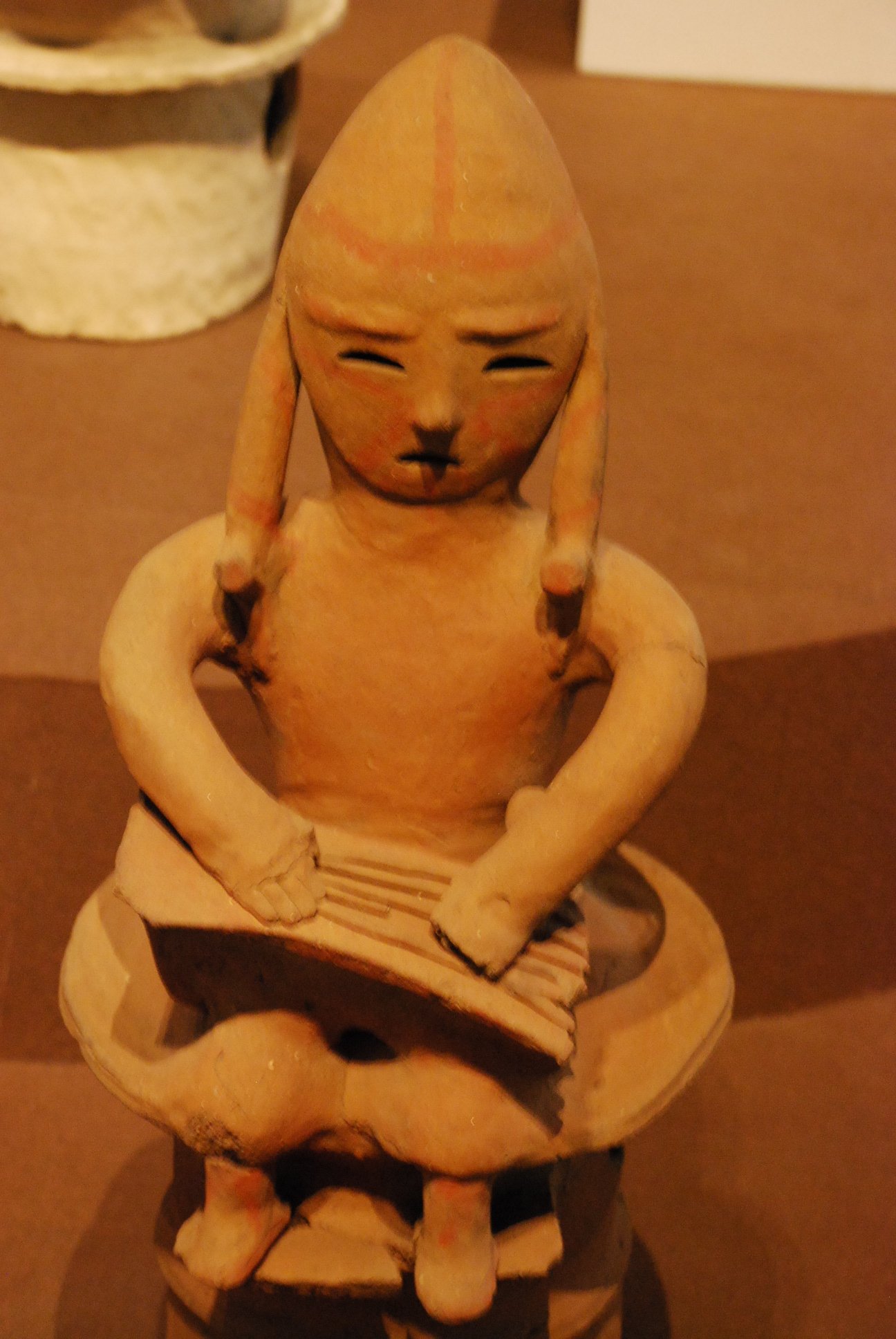

One imagines that he might have brought others from his house to take a look, or perhaps he wanted to bask in his fortune alone. Alas, his good mood was not to last—and perhaps you know where this is going. For when he got to the stables, there was no horse to be found—or at least not in the stall where he had placed the red courser. Instead, the only thing he found, standing there in the light of day, was a clay horse statue, made of the same red clay used for funerary statues.

A chill swept over Hakuson, who suddenly realized what had happened. He loaded up the clay horse and he took it back to Ichihiko Hill. Climbing the tomb mound, he found his own piebald horse, sitting there, amidst a gathering of haniwa horse statues, placed there for the spirit of the long dead sovereign. Respectfully, Hakuson took back his piebald horse, and left, in its place, the haniwa statue of the red courser that he had apparently ridden all the way home the prior evening.

This story does, I guess, at least mention the ancient ruler, Homuda Wake, and so may make some sense in the narrative, but otherwise it just feels like a kind of cool story that was put in, maybe the break up the monotony, otherwise.

It does seem to mention the continued influence of Homuda Wake, though whether this was part of his connection to the Hachiman cult or not is unclear. Certainly, the Nihon Shoki seems to be attributing to that ancient 4th century sovereign some miraculous powers if he’s able to ride about at night on the back of his clay haniwa horses.

Of course, there is a connection with Homuda Wake, as it is his regime during which Baekje is said to have sent horses to the archipelago, along with Ajikki, whose knowledge of both animal husbandry and continental literature were equally admired. We talked about him back in Episode 43.

Now there is some question about this. If Homuda Wake died in the early 5th century, it is possible that his tomb was surmounted by horses. Haniwa, which means “clay cylinder”, were originally just that, clay cylinders, sunk into the ground, some of which may have been surmounted by pots or other vessels, possibly for containing some kind of ritual offering. In the 4th century, we see some early sculptures starting to be added, such as houses and boats. In the 5th century, however, the technique had evolved to the point where both humans and animals were being depicted. Depending on when and where Homuda Wake was buried it is possible that there were haniwa horses on his tomb, though I suspect this entire story is a bit anachronistic. It does appear to be the case that horses make up the largest percentage of animal figures found at ancient tomb mounds, and so it would have made sense to anyone listening at the time that horses would have been there, but it isn’t actually clear that they were.

This also brings up a question of just where the tomb actually was. While there is certainly the kofun next to Konda Hachimangu has been traditionally identified as Homuda Wake’s grave in more recent times, most of those designations came about in the Edo period or later, as scholars tried to piece together just which tombs were being discussed in the ancient histories. Though people had lived in the area, not everyone recalled just what one pile of earth was supposed to be as opposed to another, especially after various centuries of strife and warfare, during which some times the people were just struggling to get by. And so we cannot be entirely certain of the modern designation as the tomb of Homuda Wake.

Kishimoto Naofumi provides an alternate hypothesis, suggesting that Homuda Wake’s tomb was actually a late 4th century tomb known as Tsudo-Shiroyama. This is known as the oldest of the kingly tombs in the Furuichi area, and if Homuda Wake really was the first sovereign of his dynasty in the Kawachi area, then it would make sense that it could be his. Of course, that runs us into some other chronological issues, such as the events on the Gwangaetto Stele, which may then have actually happened during the reign of Homuda Wake’s apparent son and heir, Ohosazaki, aka Nintoku Tennou.

Unfortunately, neither of these tombs appear to have haniwa horses, from what I can tell. Tsudo Shiroyama did have haniwa swans, however, and so it is possible that there were horses that just were destroyed before archaeologists could find them, but so far I have not seen evidence of horses back quite that far. It then begs the question as to whether or not the “Ichihiko Hill” could have been identified, at least by the eighth century, and whether or not there were haniwa horses on it that perhaps have not survived into modern times. Unfortunately, there are just too many questions.

And speaking of questions, these names, am I right? Hakuson and Karyu neither look nor sound like any of the Japanese names in the Chronicles so far. It is entirely possible that they were simple sinographs to record the sound of the name in the record, and as such may have been mangled in one way or another through transliteration from one source ot another. It is also possible that these originally were not ethnic Japanese at all, and that these were the names of individuals of Baekje or similar continent descent. Certainly the Kawachi area had a fair number of individuals from all over the Korean peninsula, and possibly the rest of mainland east Asia. As such, it may be that these individuals were being subtly identified by their names. Or it could just be a scribal artifact.

Hakuson, it should be noted, is considered by some to be the founder of the Tanabe house. At the very least he is the first person mentioned in conjunction with it by name.

And so that is our first story: The ghost horse of Ichihiko Hill.

Our next takes a slightly more martial tone. It takes place, or so we are told, in the latter months of the year 470, some five years after the encounter with the ghost horse. Now at that time, there was a man in the area of Miwikuma in the land of Harima, which lay to the west of modern Ohosaka, and bordered the land of Kibi, one of Yamato’s early rivals in power and prestige. This man was a bandit and a pirate, and quite strong, and he was known far and wide as Ayashi no Womaro. He robbed people both at land and in the water as they passed through the Seto Inland Sea. He was accused of committing robberies, preventing traffic, plundering merchants, and, last but not least—not paying his taxes. And, come on, we always know that the government is going to get you on your taxes, so what was he thinking?

Anyway, the court had had enough of this scoundrel, and Ohoki, of the Wono no Omi family of Kasuga, was sent out at the head of 100 fearless soldiers to deal with this threat to archipelagic commerce. The soldiers marched out and surrounded Womaro’s house, and, rather than risking men fighting the bandit, they simply set fire to his house and waited outside to either cut down or arrest anyone who came out.

Suddenly, from inside the midst of the flaming house, a giant beast burst forth. It looked like a white dog, but it was as large as a horse. The giant beast went straight after Ohoki, who was leading the government forces, but Ohoki held his ground. Drawing his sword from its sheath, he cut down the giant monster, which fell to the ground.

As it lay there, dying, the giant dog’s form began to shift, and suddenly they saw it was no dog at all, but instead it was the bandit, Ayashi no Womaro.

Now, okay, it may be a bit of a stretch to really consider this a true werewolf tale. After all, they specifically said he had turned into a dog, not a wolf, and there is no indication that this was a regular occurrence. It could have been some supernatural event that happened just at that time. More likely, I suggest that it was simply a narrative tool to dehumanize the antagonist and thus remove any ambiguities about the righteousness of Ohoki’s—and by extension, the court’s—actions in this matter.

Of course, how such a story gets started is not entirely clear. Was this just a story that got modified over time until it was downright ridiculous? Or was there some grain of truth in it to begin with, which then grew more and more fantastical as time went on? Who can say for certain.

There definitely is a connection with traditional Japanese myths and legends, however, as shapeshifters are quite common. In fact one of the words for ghosts and other monsters, “bakemono”, specifically references their ability to change shape. Foxes, or kitsune, as well as the raccoon dog, known as tanuki, are both thought to possess shapeshifting abilities, though they each tend to use them in different ways. Even cats and other animals can sometimes get in on the action.

As for why this merited a place in the Nihon Shoki, I’m not entirely clear. I guess, yes, technically Ohoki was dispatched by the sovereign, so that may have been enough. Furthermore, he may have been an important figure in some later courtier’s family tree, but he doesn’t appear to show up in the rest of the narrative about Ohohatsuse, aka Yuryaku Tenno.

The story does suggest a few things for us, though they may be things we already know from previous books. For example, we can see that bandits were still a problem, both on land and on sea. We’ve talked about the issue with the Seto Inland Sea before, and how it makes up for its seemingly calm waters with many possible coves and islands in which pirates could potentially lurk. Furthermore, I highly doubt that it was simply a single man who was causing all of these problems. It was probably him and his band, but that often gets translated as though it was just one man of exceptional strength.

And so that is the story of Wono no Omi no Ohoki and the werewolf—so to speak—of Miwikuma, in the land of Harima.

And that brings us to the main tale of the evening, the tale of Urashima Taro. It goes a little something like this.

In the year 478, the child of Mizunoye no Urashima, a man from Tsutsukawa in the district of Yosa in the land of Tamba—which is to say modern Kyoto Prefecture, decided to shove off from land in a boat to go fishing. There he caught a turtle, which eventually changed itself into a beautiful woman. The child of Urashima—also known as Urashimako—fell in love with this turtle-woman, and made her his wife. Togetehr, they went down into the sea, where they reached the mythical Mount Hourai, aka the Land of the Immortals, Mt. Penglai, where they saw many kami.

Now it may be more accurate that this man’s name was actually Shimako, from Midzunoe no Ura—the shore of Midzunoe—but this isn’t certain.

In the Nihon Shoki, this story ends rather unsatisfactorily with the note that the rest of the story is in another book, though we are not told which and I highly suspect it is no longer extant. And so we are left with a fragment of the story, like a television series cancelled just after the big cliffhanger ending. Fortunately, this was apparently a popular story, and so it has cropped up in a few other places. Notably, we have two other sources from around the same time that give us details. The first is the Man’yoshu, a collection of thousands of poems, in which we get this story, told in poetic form, including notes about Urashima-ko’s eventual return from the land of the immortals some three years later—or at least three years for him.

The other ancient source for this story is fragments of the Tango Fudoki, which was actually which was ordered to be compiled in 713, some seven years before the Nihon Shoki was published.. The Tango Fudoki itself is no longer extant, but some passages, including the Urashima legend, were recorded in the “Shaku Nihongi”, a commentary on the Nihon Shoki compiled in the Kamakura period.

In the fragments of the Tango Fudoki we are told that Mizunoe Urashima no Ko, also known as Tsutsukawa no Shimako, was not only a fine looking man, but he was an ancestor of the Kusakabe no Obito. As with the Nihon Shoki’s version, the Tango Fudoki agrees that this took place during the reign of the sovereign Ohohatsuse, identified here by his palace of Asakura no Miya. Urashima no ko went out fishing in a small boat, and he was out there fishing for three days and three nights, but didn’t catch any fish. He did, however, catch a strange looking turtle.

Urashima no Ko woke the next day to find that the turtle had transformed into the most beautiful woman Urashima no Ko had ever seen. As they were talking, the woman told Urashima no ko her story, saying she was from a heavenly, immortal place. She then told him to go to sleep.

When he awoke, it was a marvel. They had arrived at a big island, but not like any island Urashima no Ko had heard of, for this island was under the very sea itself. When they entered the gates of the palace there, he saw two groups of children—seven on the one hand, and eight in the other. They claimed to be the stars of Subaru and Amefuri—the constellations known to the Greeks as the Pleiades and the Hyades cluster—the latter in the larger constellation known as Taurus.

The family of the woman welcomed Urashima no Ko, and during the entertainment, she told him about the differences between the human world and the world of immortals. And so he stayed there with them for three years.

After a while, however, he began to get homesick, yearning for the mundane world.

His wife gave him a tearful goodbye, handing him the gift of a jeweled casket, warning him that if he ever wished to return to the land beneath the waves he should never open it.

When he arrived back at his village, things had changed, so that he didn’t recognize it. He found a man in the village, and upon inquiring as to what had happened he was told the story of Urashima no Ko, who went to sea but never came back.

Urashima no Ko eventually opened the jeweled casket, and it was as if something flew out into the clouds. Urashima no Ko realized that what he had been told was true, and that he would never be able to go back and meet his beloved beneath the waves in the land of the immortals.

There is one more book, from the Kamakura period, which tells us that Urashima no Ko’s return was in the year 825—in other words, while three years had passed in the realm of the Immortals, some three hundred had passed in the human world, above the waves.

This story has since been told many times, changing as it went. Instead of Urashima no Ko, which means the Child of Urashima, he would eventually be named Urashima Tarou—literally the eldest son of Urashima. And the land of the immortals was eventually equated with the palace of the Dragon King.

Of course, that last bit is hardly surprising. If you remember the story of Hiko Hohodemi and his brother, which we visited back in Episode 23, one notices more than a few similarities. In both cases they end up descending beneath the waves, and they both find women who are daughters of the lord of that land beneath the sea. They are both welcomed in and entertained. And in both cases—at least in some of the stories—they tire of their paradise in three years, each wishing to return to the land.

Of course, that is largely where similarities end. After all, Hiko Hohodemi returns, bests his brother, and ends up continuing the Heavenly line. Urashima no Ko, on the other hand, finds himself tossed three hundred years into the future. Everyone he knows has passed away, and he eventually disobeys what his wife and her family told him and loses any hope of returning to the Island of the Immortals.

Speaking of which, that seems a nice continental touch, referencing the ancient island of Mt. Penglai, which I talked about back in Episode 10. This mountain was said to be far in the Eastern Sea, and during the reign of Qin Shihuangdi there were attempts to find it and the herb that grew there, which was said to grant immortality. Of course, some equated that island with Japan itself.

It is interesting how these various elements, both local and continental, can be found time and again in these stories. I suspect that tropes like these provided storytellers a kind of shorthand with which to better remember and record details. By drawing on similar experiences, there were actually fewer unique details to remember, and even the audience would find familiarity in what was going on and what was happening. Still, it makes me wonder whether these were evolutions of some ur-story, which developed differently in different parts of the archipelago, or if they were simply borrowing common elements from stories at the time.

But that concludes our stories for now. I have to admit that the first story, about Homuda Wake’s ghost horse, is probably one of my favorites. That may simply be the idea of the haniwa horse, however, which I particularly enjoy. Regardless, I’m glad for all of them—a bit of something different to break up what is going on. Of course, it is quite likely that these stories are not actually related to the fifth century, but rather come from a much later period, when the time of Ohohatsuse no Ohokimi was the ancient past—which in and of itself says something about Wakatake’s reign.

Speaking of Waketake, we *will* be touching on him more next episode. I’m still working out in just what way, but have no fear, he will be making an appearance. And you, yourself, can judge his actions—or at least those we have been told about.

Until then, thank you for all of your support. If you like what we are doing, tell your friends and feel free to rate us wherever you listen to podcasts. Ratings do help people find the show, and thus is one way to share it with others. If you feel the need to do more, and want to help us keep this going, we have information about how you can donate through our KoFi site, kofi.com/sengokudaimyo, or find the link over at our main website, SengokuDaimyo.com/Podcast, where we will have some more discussion on topics from this episode.

Also, feel free to Tweet at us at @SengokuPodcast, or reach out to our Sengoku Daimyo Facebook page. You can also email us at the.sengoku.daimyo@gmail.com. We would love to hear from you and your ideas.

And that’s all for now. Thank you again, and I’ll see you next episode on Sengoku Daimyo’s Chronicles of Japan.

References

Kishimoto, Naofumi (2013). Dual Kingship in the Kofun Period as Seen from the Keyhole Tombs. UrbanScope: e-Journal of the Urban-Culture Research Center, OCU. http://urbanscope.lit.osaka-cu.ac.jp/journal/pdf/vol004/01-kishimoto.pdf

Aston, W. G. (1972). Nihongi, chronicles of Japan from the earliest times to A.D. 697. London: Allen & Unwin. ISBN0-80480984-4