Shōgi (将棋), also referred to as “Japanese chess,” is one of the better known Japanese board games. Like Western chess, it began in India, and was introduced to Japan via China in the Nara Period. Also like Western chess, there were many early variations, primarily identifiable by the number of spaces on the board and the number and type of playing pieces used. It is not clear exactly how shōgi was played in Nara days, but during the Heian Period, several predominant forms emerged.

Modern shōgi is similar to a Muromachi variant to which had been added two pieces brought in from yet another variation on the game.

Play

The shōgiban, or shōgi board, is a nine-by-nine grid. Each player has 20 pieces (koma) which are all identical — elongated pentagons — that point towards the other player. The pieces lay flat, but they are slightly sloped (that is, the rear is slightly higher than the pointed front). They are uniform in shape, but are distinguished by the characters painted on them. The fuhyō (pawns) are the only characters of different size than the others, being smaller than the rest. (Some beginner’s sets today have the pieces marked to indicate how they may move.)

Pieces that have been captured are put on the right side of the capturing player’s board, and may be returned by that player to the board as his own pieces.

Shōgi pieces

The figure on the left is the face of the koma; that on the right is its reverse. The blocked kanji show the official abbreviation of that piece as used in board layouts.

Kakugyō (角) / Ryūma (馬) - 1 per player

Hisha(飛) / Ryūō(龍・竜) - 1 per player

Keima(桂) / Nari-kei(圭・今) - 2 per player

Kyōsha(香) / Nari-kyō(杏・仝) - 2 per player

Ginshō(銀) / Nari-gin(全) - 2 per player

Gyokushō (玉)/ (No Reverse) - 1 (player 1)

Ōshō (王)/ (No Reverse) - 1 (player 2)

Kinshō(金)/ (No Reverse) - 2 per player

Fuhyō(歩) / Nari-fu(と・个) - 9 per player

The above graphic depicts the pieces in a shōgi set. The kanji displayed with each piece is the conventional “abbreviation” of each name, and is how they’re marked in printed layouts of a game in session. It’s also how the koma are marked in the board layouts below. The reverse of the ginshō, keima, and kyōsha traditionally have different calligraphic variations of the same character — namely “kin” (= gold), as they all share the same moves when promoted (that of the kinshō). The different calligraphic style helps the player keep track of which piece is the narigin or the narikei. Such detail is, of course, irrelevant to beginning players—and, of course, irrelevant in the pieces’ moves on the board.

Instead of each player having a king, one has a king (ōshō, also called ō) and the other a jewel (gyokushō, also called gyoku). They move identically to the Western chess king — one space in any direction — and are only differenced from each other by the name and the character used to write each. (Interesting bit of trivia: the characters for “king” and “jewel” differ by only the addition of a single stroke. Originally there were two kings on the board, one on either side; but a sovereign in distant antiquity reasoned that, since there was but one sovereign under heaven, there should only be one king on the board—hence the jewel.)

The hisha resembles the rook in that it can move an unlimited number of spaces forward, backward, or to either side—thus its English name. There is only one per player.

The kakugyō (also called kaku) moves diagonally an unlimited number of spaces, and so is sometimes called the bishop, whose moves in chess it duplicates. As with the hisha, there is only one per player.

The keima (also called kei) can move only forward two and then left or right one, identical to a Western chess knight. Unlike the knight, however, as it must go forward it has only two possible moves, while a Western knight can land on one of eight possible squares. Like the Western knight, the kei is the only piece allowed to jump over others. There two per player.

The kinshō (= gold general, also called kin) moves one space in any direction except diagonally backwards, while the ginshō (= silver general, also called gin) moves one space in any direction except sideways or backward. There are two per player.

Kyōsha (= lancers, also called kyō) may move an unlimited number of squares straight ahead; it may not retreat. There are two per player.

The fuhyō, or pawn (also called fu), advances in a straight line one space at a time. Each player has nine.

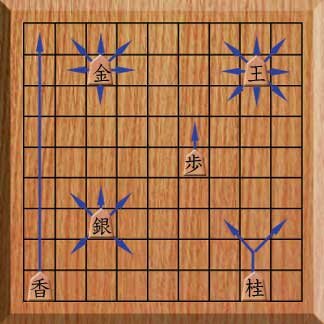

See below for a visual representation of the moves of each piece:

Like chess, if an enemy piece is on the space where a piece’s movement would end, it may be captured.

“Nari” is the promotion of a player’s own pieces, and may be done by entering one’s piece into the home territory of the opponent (the far three rows). Whether to take the advancement or not is purely optional, although the advantages are many and the detriments virtually nonexistent. The pieces are turned over to reveal their new names. All save the ōshō or gyokushō and kinshō may be promoted and get new moves. The hisha becomes a ryūō (= dragon-king, ryū for short) and combines the potential moves of the hisha and ō. The kaku becomes a ryūma (= dragon-horse) and can move like the kaku and ō. The gin, kei, kyō, and fu become respectively the narigin, narikei, narikyō, and tokin, and all adopt the move potential of the kin. (Note: when captured, these pieces revert to their original “lowly” status, should the capturing player choose to return them to the board.)

“Haru” is the use of a captured piece to supplement one’s own supply. One turn may be given to place a captured piece on the board rather than move another one. The piece can be placed in any open square. The only restrictions are that only one fu from either side can occupy a file at a time (a player may not place a second fu in a row where he already has one enfiled), no piece can be put down where it doesn’t have an opening to move, and an enemy “king” cannot be placed in checkmate by laying down a fu.

The board is set up as in the illustration below at the start of play. (The player who has an ōshō places his in the place occupied by the gyokushō in the illustration instead.) Both sides use this same layout—with the kakugyō on the player’s left and the hisha on the player’s right) so that their kakugyō and hisha will be on opposite sides.

To make your own quick’n’dirty shōgi set, copy the pieces in the first graphic onto heavy paper (don’t forget the bottoms!) and cut them out, and play on a board marked with 81 squares.

Alternately, you can order the pieces from one of the resources below. They come in plastic or wood, and in all price ranges. A cheap set of plastic koma are only a few dollars, while the finest handmade wooden ones with carved characters can cost serious shōgi professionals as much as ¥200,000–¥800,000 (yes, you’re reading that right; just the pieces can cost up to $7,500). The boards can be purchased separately, and range from good, solid heavy folding wooden ones for about $25 up to big monsters with stands and the whole rig for serious shōgi professionals for about ¥89,000. You can also buy a full shōgi set with the board and pieces; again, these come in all price ranges.

Online resources: