A tantō, or dagger, with the koshirae, or fittings

Although it is frequently stated that carrying two swords is a mark of the samurai, this is not true. At least, it was not true for the most periods. It wasn't really till the Edo period that such sumptuary laws came into enforceable effect. In point of fact, just about anyone during those anarchistic days of the end of the sixteenth century could carry or wear anything that they could get away with. Remember Mifune's character in the film Seven Samurai? What a sword!

During the early period, warriors and courtiers alike wore a single long sword, called a tachi. They would often tuck a second, shorter, blade into their sashes. This second blade later became longer and became the wakizashi, the companion sword to the katana, which was what the longer sword metamorphosed into.

The most striking difference between tachi and katana is that the former is worn suspended from the waist, edge down, while the latter is thrust through the sash and worn edge up. When we speak of tachi-mounts or katana-mounts, we are referring to swords with furniture specifically designed to suit one or the other way of wearing. In fact, it is primarily the fittings and furniture that determine what a sword is, as many tachi were later put in katana mounts. If the sword is signed, you can sometimes tell what the smith intended, as the signature is supposed to be facing out when worn, even though it isn’t seen. Otherwise, you can usually assume that blades from before the the Sengoku period were meant to be tachi and anything later was probably meant as a katana, with some notable exceptions.

A nice tachi with clean, not overly ornate fittings.

A pair of swords—a daishō—in a classic, clean, set of fittings.

Japanese swords are single-edged, though there are occasional exceptions found in some older swords, in which the front third of the back of the blade is also a cutting edge. There was an ancient sword style called ken, which was similar to the Western sword in having a long, tapering straight blade with edges on both ends terminating in a point. Occasionally the subject of a swordsmith's work today, ken generally tend to turn up as swords dedicated to shrines and temples.

Older tachi were straight, and often much shorter and narrower than later tachi and katana; some were much larger. The shortest swords, what we may consider dirks, often were in very simple mounts, and may have even lacked a guard. For the vast array of sword types and fittings, take a look at the bibliography.

Safety First!

It probably doesn’t need to be said, but swords are weapons, and should be treated as such. Even though we are largely talking about dress swords, every sword should be treated as though it is a live blade. This goes for wooden training swords as well. You should always have positive control of your weapons. While a new sword should be pressure fit to its scabbard, it is often the case that modern swords are matched to generic scabbards, and therefore the fit will not be great. Furthermore, the fit will change over time—even a change in humidity can make a difference as the scabbards are made out of wood. So never trust that the weapon will simply stay in its scabbard.

When worn properly, the sword should fit so that the hilt is either forward or slightly up, and the back of the scabbard is down. That way gravity does all the work for you. However, as we start to move, run, or do other things, that position can change. Most common is when people are bowing or bending down to pick something up and they forget about the sword, which can then come tumbling out.

To prevent this, you should get used to having your left hand on the sword, grasping the scabbard near the hilt, and having at least one finger—usually the thumb, but sometimes the index finger—holding the sword guard to prevent it from slipping out. What if you need to carry something with two hands? In many cases it may be best to just put your sword down until you can come back for it, or at least adjust its position so it is more vertical. As you grow more experienced it will become second nature.

Even with all of this, accidents may happen. If a sword starts to fall, let it. Most of the time, when a sword falls out, people will just back away and let it come to rest. Then you can pick it up and put it back in the scabbard.

If you try to stop the sword from coming out of the scabbard you may miss. One or both of your hands may grasp the blade, which is, at that point, moving. Even if the sword isn’t sharp, any burr or inperfection on the blade can cut up your hands pretty bad. Also, the point is still sharp, and if you lunge forward at the wrong time you could still impale a hand, a leg, or worse on the end of the sword. It is best just to back away until the sword comes to rest and then go and pick it up.

Always practice good habits and good discipline, because the habits you develop with a dress sword are the same ones you will employ if you ever encounter the real thing.

Reworking the fittings

There is no reason why one need make do with the standard mountings that come with so many touristiana swords. As they are almost all virtually Edo style, and not all are acceptable for all periods and purposes (court sword fittings being very different from those for field use), some may choose to buy a single sword and make two or three sets of different mounts for it. This is what I have done. But be warned that you need to buy a sword that has the appropriate lines for a Japanese sword (see below, “Caveat emptor”).

If this is just for wearing at events, don't be carried away by getting a spectacular blade; and if you practice a particular style of swordmanship, check with your teacher. For our purposes, though, what is more important is the fittings, making the sword look correct for the impression you're trying to give. A duraluminum dress blade is fine for such a purpose. You may also want to dress up a sword for steel combat, such as cut and thrust. Either way, the mounts are the important part.

Your first choice will be deciding on tachi or katana mounts. There is a vast array of alternative decorations, however, suiting different periods and different purposes; far too many to list or present here. Again, the advice is the usual “go crazy, have fun.”

Care and feeding of a Japanese sword

Those lucky enough to own a real blade probably already know how to care for it. There are special sword-care kits which contain tissue paper, a small bottle of clove oil, and what looks like a cloth-covered lollypop. The last is called a uchiko, and is filled with a fine powder that helps remove residue from a blade; it is sort of like a very soft polishing process.

The old oil is first wiped off the blade, and then the uchiko is applied, tapping softly once on the blade every six inches or so. This is then wiped off, taking any remaining oil with it. (Be careful in the wiping if your sword has an edge; always wipe from the hilt towards the point; this is to prevent injury.) Then apply the clove oil to the blade, wiping it down, and return it to the scabbard.

A word on the clove oil; yes, it smells good, but don't go overboard. Some people maintain that unless it really strongly smells of clove, you aren't using enough. The truth is, if you have oiled the whole blade, regardless of the aroma, that is enough. In fact, you shouldn’t “see” oil on the blade—if the oil is pooling on the metal surface, then when it gets put back in the scabbard the oil can seep into the wood. Over time this can get sticky and the oil can even go rancid, depending on the quality. A very thin layer of oil is all you need to coat the metal and prevent it from rusting.

Sometimes, swords are stored in plain wooden scabbards and with plain wooden hilts. If you were to buy a blade from a smith, this is probably how you would receive it. This fitting is called “shirasaya” (= white scabbard) as shown at right. It isn't appropriate to carry or wear swords in such mounts, as they're only for storage, to keep the blades clean.

When drawing the sword or returning it to the scabbard, you should draw it edge up, with the spine of the sword running along the inside-top of the scabbard. This prevents the scabbard from possibly marring the surface of the blade. If it is sharp, it also prevents the blade from chewing up the inside lip of the scabbard and possibly your palm as it clears.

A special note here: If you are drawing a blade to look at it, don’t draw the blade from the saya as much as lift the saya off the blade. To do this, first grasp the hilt of the sword with your dominant hand, and ensure the point is facing away from you or anyone else where you can see and control it. Next, make sure that the saya is loose—you can usually do this by placing your other hand around the mouth of the scabbard, up against the sword guard, and squeezing, slightly. This should create enough pressure to gently loosen the scabbard. You can then grab it underneath and slide the scabbard carefully off of the sword.

There is nothing more painful than to hand someone your sword and watch them draw like they are in a Kurosawa film and hear the telltale scrape of wood and metal as the blade scratches up the inside of the scabbard. The above method shows respect, is less likely to cause damage (even if you are a 20th degree black belt), and ensures everyone’s safety as the only thing that should be moving is the scabbard, while the blade itself remains firmly under your control.

When handing an undrawn sword to someone of equal or greater rank, it should be with both hands open and palm up, one under the hilt, one under the scabbard, with the edge towards you and with the hilt towards the other person's right, so they could immediately use it, which shows trust. To someone of inferior rank, you can use one hand, your right, palm down, in the middle of the scabbard. Always be careful, though. Most swords are pressure fit to their scabbards, but over time they can come loose. Always be cognizant of the fit of the sword and, if necessary, hold the hilt just slightly higher, and never lower.

If offered the sword by a person of higher or equal rank, the recipient will grasp it from below with both hands. If offered by a person of lower rank, then grasp it from above with one hand. Very simple, really.

Offering a drawn sword for inspection is easy; hold the sword at the very base of the hilt, holding the sword upright, with one hand (many sources say left) with the edge toward you. The recipient will grasp the hilt below the guard; this puts him in a position to cut right down and take your arm off.

That is the idea.

It should be returned the same way. One thing implied in this is respect for the person receiving the sword; you are putting him in the dominant position. You are also saying, “I trust you.”

Although there is some debate over showing a completely drawn sword, most agree that the sword should be completely drawn before it is examined. There are several reasons for this. One is that you can't really examine anything without looking at it all. Another is that turning the blade over and moving it around in the scabbard for viewing could scar the blade against the lip of the scabbard. Yet a third is that some feel it shows disdain, as if the whole thing weren't worth looking at.

When sitting or kneeling, if wearing a katana, take it out and place it along your right side, edge in. This makes the sword inconvenient to get to and draw, and shows the proper respect. A great way to deliver a not-so-subtle insult (“I don't trust you; I could kill you, you know,”) is to leave you sword on the left side, edge out.

The key to remember about all of this is that the respectful attitude with swords is to indicate that it would be difficult for you to draw, cut, or otherwise defend with it, while the other person would find it easy to attack you.

Of course, if you genuinely don't trust the other guy, you wouldn't hand him a weapon to begin with, let alone put the thing out of your reach.

When not in use or being worn, your sword should be properly put away on a sword stand. The one on the left is for tachi. Note that when properly on the stand, the hilt is down. This shouldn't be a problem, as the hilt will rest on the bottom of the stand, as long as you remember to always grasp the sword by the hilt or tsuba when grabbing it, so that it doesn't accidentally fall out of the scabbard.

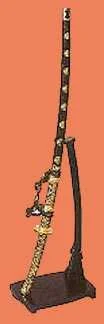

Katana and wakizashi are placed horizontally (edge up, of course) on a stand called a katana kake. A typical model is shown at right. Some were made to hold many swords; this one only holds a pair.

One final rule: there is no such thing as a requirement that once drawn, a Japanese blade must be blooded before it can be returned to the scabbard. This is not Barsoom, nor a Ghurka camp. If that were true, pity the poor souls studying iai-dô (the art of drawing and striking), who in the course of a practice session draw their blades several hundred times.

Really, where do these stories start?

Caveat emptor

The swords displayed here are evil, all in their own ways. I expect people who are doing Japanese in reenactment groups to have the good taste to neither purchase, nor carry, such atrocities.

One of the first problems is swords that are cut from solid bar stock, whether spring, stainless, or what have you. Technically, this isn't a problem. The problem is this: many of these manufacturers are cheap. Plain and simple. They want to produce the most swords from the least amount of steel possible. While the blade may have a curve, what is happening is that to fit the sword on the narrow piece of steel stock, they've ended the curve before the tang, and in doing so, really totally destroyed the appropriate (and aesthetic) lines of a good Japanese sword. First, take a look at the katana blade below. Notice that the curve continues, unbroken and unabated, from point to tip of tang.

Now take a look at the following two crapblades. If you look at them carefully, you will notice, just at the tsuba, that the curve goes briefly on vacation. This is the sort of thing to avoid like the plague. (This reason, of course, is in addition, of course, to the atrocious fittings on these swords, which alone should be enough reason to avoid them.)

The curve is very subtle here, but if you look at the lines carefully...

The problem is more pronounced here; there is clearly a curve for the blade, and a curve for the hilt, both of which meet at the guard.

Even though the swords may be well tricked out (as in the case of the tachi above; I trust I needn't go into the problems with the sword above it), the aesthetic problem with this method of manufacture should eliminate such swords from consideration by people who appreciate Japanese blades.

The swords below is clearly totally inappropriate for reenactment purposes; indeed, short of just buying a sword to actually swing around and chop on things, there is no reason to buy abominations like either of these two. The one on top is just Wrong, and it should be no secret that Japanese swords were not made like kitchen knives, as the daishô on the bottom would indicate. Despite whatever hype the manufacturers may come up with (“guaranteed not to come apart under harsh use!”) one must stop and think. The Japanese have been making swords the way they have for a thousand years and more. I think they know what they're doing. What would you be doing that you would be that worried that the thing might come apart?

They have the nerve to call this "Japanese."

And who ever carried anything like these?

One of my favorite bugaboos is people wearing kilts and carrying katana. It just didn't happen. And no swordsmith or sword furniture maker worth his salt would make an abomination like the katana shown below. This is a fantasy piece. It may have a place at a science fiction convention, but it has none in any re-enactment or otherwise historically based group. If you must buy one, don't tell me about it, and please leave it at home when you go off to an event.

I don't care if McLeod is a good guy. This is evil.

Online resources

Japanese Sword site. This is a great place to start looking for information.