Previous Episodes

- July 2025

- June 2025

- May 2025

- April 2025

- March 2025

- February 2025

- January 2025

- December 2024

- November 2024

- October 2024

- September 2024

- August 2024

- July 2024

- June 2024

- May 2024

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

Continuing on our journey along the path mentioned in the Gishiwajinden - the Wa section of the Weizhi. We are now in Tsushima. A border island between the archipelago and the peninsula.

This is the first island attacked by the Mongol invasion, and the last one passed by Japanese raiders headed to the Korean peninsula. It was visited by missions from Tang China, the Joseon Kingdom, and others. It is a rocky, mountainous place, wholly unsuited to the style of agriculture brought over in the Yayoi period, and yet it continued to support a population based on the sea—whether fishing or trading or… other activities.

In the flora and fauna you can see bits of the peninsula, from the wild leopard cat to species of birds and more. Ancient assemblages of artifacts similarly show a duality about them, demonstrating its position in between various cultural spheres.

Today it is perhaps not on everyone’s bucket list, but it is certainly a short stop from Korea, or just a short flight from Kyushu, and it has its own local charms.

-

Welcome to Sengoku Daimyo’s Chronicles of Japan. My name is Joshua and this is Gishiwajinden Tour Stop 2: Tsushima.

As I mentioned last episode, we are taking a break right now from the workings of the Chronicles while I prep a bit more research on the Taika reform. As we do so, I’m taking you through a recent trip we took trying to follow the ancient sea routes from Gaya, on the Korean peninsula, across the islands to Na, in modern Fukuoka. This may have been first described in the Wei Chronicles, the Weizhi, but it was the pathway that many visitors to the archipelago took up through the famous Mongol invasion, and even later missions from the Joseon kingdom on the Korean peninsula.

Last episode, we talked about our start at Gimhae and Pusan. Gimhae is the old Geumgwan Gaya, as far as we can tell, and had close connections with the archipelago as evidenced by the common items of material culture found on both sides of the strait. From the coast of the Korean peninsula, ships would then sail for the island of Tsushima, the nearest of the islands between the mainland and the Japanese archipelago. Today, ships still sail from Korea to Japan, but most leave out of the port of Pusan. This includes regular cruise ships as well as specialty cruises and ferries. For those who want, there are some popular trips between Pusan and Fukuoka or Pusan all the way to Osaka, through the Seto Inland Sea. For us, however, we were looking at the shortest ferries, those to Tsushima.

Tsushima is a large island situated in the strait between Korea and Japan. Technically it is actually three islands, as channels were dug in the 20th century to allow ships stationed around the island to quickly pass through rather than going all the way around. Tsushima is the closest Japanese island to Korea, actually closer to Korea than to the rest of Japan, which makes it a fun day trip from Pusan, so they get a lot of Korean tourists.

There are two ports that the ferries run to, generally speaking. In the north is Hitakatsu, which is mainly a port for people coming from Korea. Further south is Izuhara, which is the old castle town, where the So family once administered the island and relations with the continent, and where you can get a ferry to Iki from.

Unfortunately for us, as I mentioned last episode, it turned out that the kami of the waves thwarted us in our plans to sail from Busan to Tsushima. And so we ended up flying into Tsushima Airport, instead, which actually required us to take an international flight over to Fukuoka and then a short domestic flight back to Tsushima. On the one hand, this was a lot of time out of our way, but on the other they were nice short flights with a break in the Fukuoka airport, which has great restaurants in the domestic terminal. Furthermore, since we came into the centrally-located Tsushima airport, this route also gave us relatively easy access to local rental car agencies, which was helpful because although there is a bus service that runs up and down the islands, if you really want to explore Tsushima it is best to have a car. Note that also means having an International Driver’s Permit, at least in most cases, unless you have a valid Japanese drivers’ license.

As for why you need a car: There is a bus route from north to south, but for many of the places you will likely want to go will take a bit more to get to. If you speak Japanese and have a phone there are several taxi companies you can call, and you can try a taxi app, though make sure it works on the island. In the end, having a car is extremely convenient.

Tsushima is also quite mountainous, without a lot of flat land, and there are numerous bays and inlets in which ships can hide and shelter from bad weather—or worse.

Tsushima is renowned for its natural beauty. Flora and fauna are shared with continent and the archipelago. There are local subspecies of otter and deer found on the islands, but also the Yamaneko, or Mountain Cat, a subspecies of the Eurasian leopard cat that is only found in Japan on Tsushima and on Iriomote, in the southern Okinawan island chain. They also have their own breed of horse, as well, related to the ancient horses bred there since at least the 8th century.

Tsushima is clearly an important part of Japan, and the early stories of the creation of the archipelago often include Tsushima as one of the original eight islands mentioned in the creation story. That suggests it has been considered an ancient part of the archipelago since at least the 8th century, and likely much earlier.

Humans likely first came to Tsushima on their crossing from what is now the Korean peninsula over to the archipelago at the end of the Pleistocene era, when sea levels were much lower. However, we don’t have clear evidence of humans until later, and this is likely because the terrain made it difficult to cultivate the land, and most of the activity was focused on making a livelihood out of the ocean.

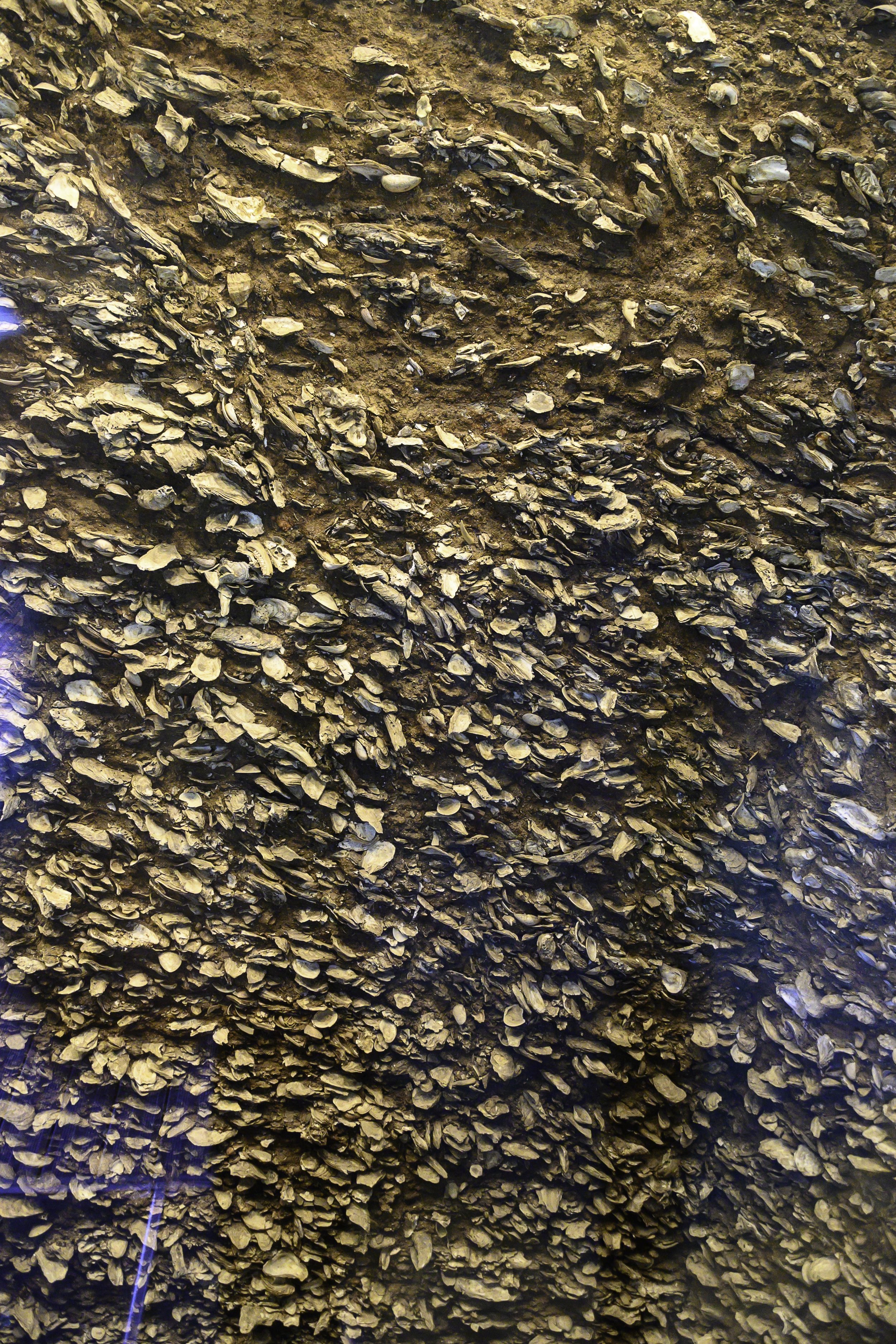

Currently we have clear evidence of humans on the island from at least the Jomon period, including remnants such as shellmounds, though we don’t have any clear sign of habitation. It is possible that fishermen and others came to the islands during certain seasons, setting up fish camps and the like, and then departed, but it could be that there were more permanent settlements and we just haven’t found them yet. Most of the Jomon sites appear to be on the northern part of Tsushima, what is now the “upper island”, though, again, lack of evidence should not be taken as evidence of lack, and there could be more we just haven’t found yet. After all, sites like Izuhara, which was quite populated in later periods, may have disturbed any underlying layers that we could otherwise hope to find there, and perhaps we will one day stumble on something more that will change our understanding.

Things change a bit in the Yayoi period, and we see clear evidence of settlements, pit buildings, graves, and grave goods at various sites up through the Kofun period. Unsurprisingly, the assembly of goods found include both archipelagic and continental material, which fits with its position in between the various cultures.

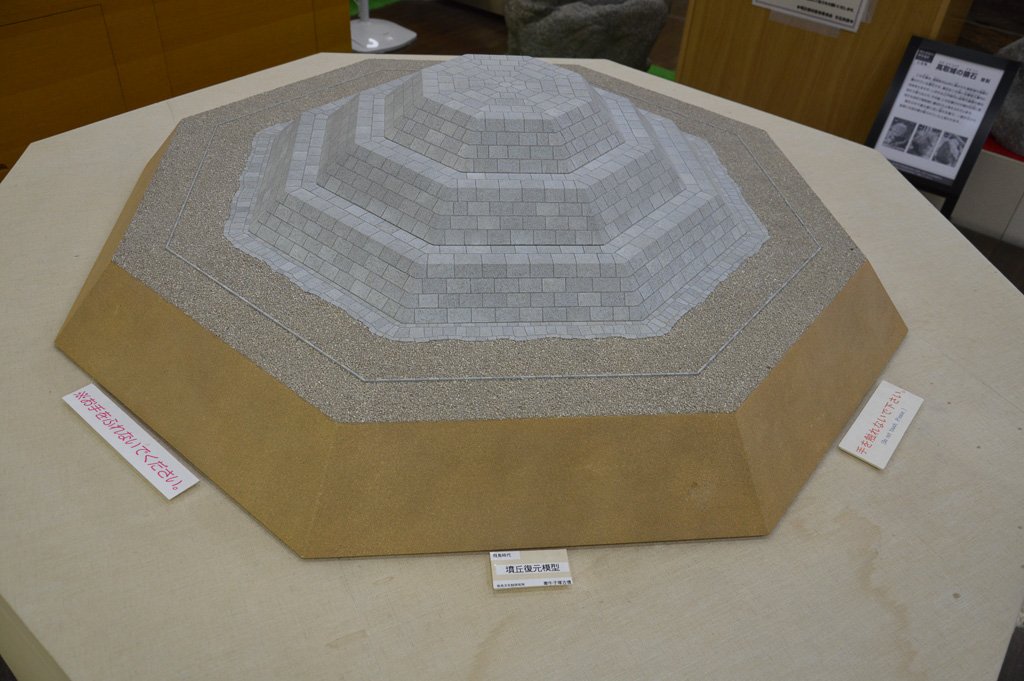

Understandably, most of these archeological sites were investigated and then either covered back up for preservation or replaced by construction – so in many cases there isn’t anything to see now, besides the artifacts in the museum. But some of the earliest clear evidence that you can still go see today are the several kofun, ancient tumuli, scattered around the island at different points.

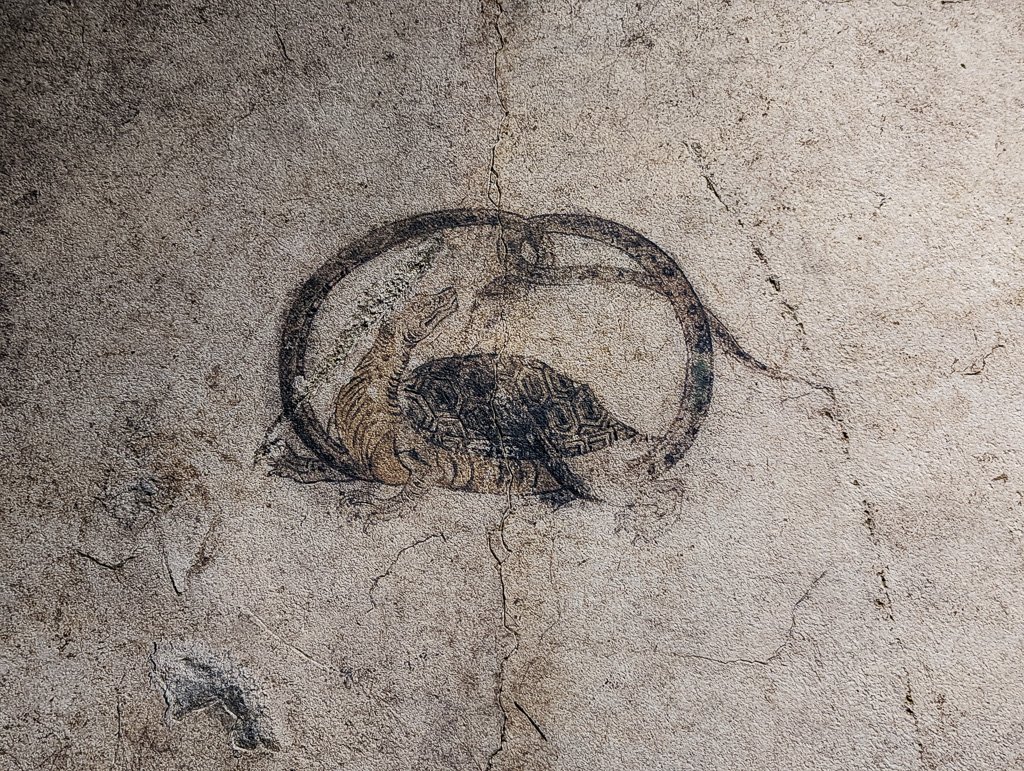

Most of the kofun on the island appear to be similar, and overall fairly small. These are not the most impressive kofun—not the giant mounds found in places like Nara, Osaka, Kibi, or even up in Izumo. However, to students of the era they are still very cool to see as monuments of that ancient time. One example of this that we visited was the Niso-kofungun, or the Niso Kofun group. The Niso Kofungun is not like what you might expect in the Nara basin or the Osaka area. First, you drive out to the end of the road in a small fishing community, and from there go on a small hike to see the kofun themselves. Today the mounds are mostly hidden from view by trees, though there are signs put up to mark each one. Some of them have a more well defined shape than others, too, with at least one demonstrating what appears to be a long, thin keyhole shape, taking advantage of the local terrain. Most of these were pit style burials, where slabs of local sedimentary rock were used to form rectangular coffins in the ground, in which the individuals were presumably buried. On one of the keyhole shaped mounds there was also what appears to be a secondary burial at the neck of the keyhole, where the round and trapezoidal sections meet. However, we don’t know who or even what was buried there in some instances, as most of the bones are no longer extant.

Besides the distinctively keyhole shaped tomb, two more kofun in the Niso group caught my attention. One, which is thought to have been a round tomb, had what appeared to be a small stone chamber, perhaps the last of the kofun in this group to be built, as that is generally a feature of later period kofun. There was also one that was higher up on the hill, which may also have been a keyhole shaped tomb. That one struck me, as it would likely have been particularly visible from sea before the current overgrown forest appeared.

There are also plenty of other kofun to go searching for, though some might be a little more impressive than others. In the next episode, when we talk about the island of Iki, we’ll explore that ancient kingdom’s much larger collection of kofun.

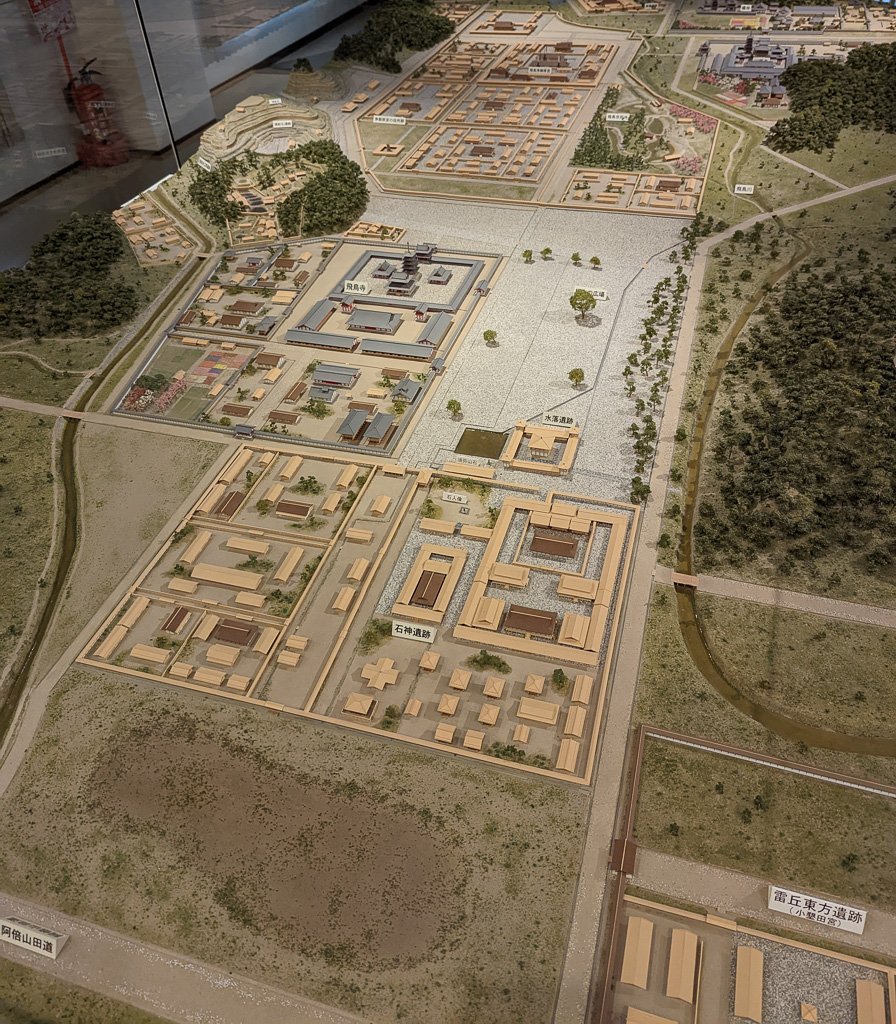

After the mention of Tsushima in the Weizhi in the third century, there is a later story, from about the 6th century, involving Tsushima in the transmission of Buddhism. This story isn’t in the Nihon Shoki and was actually written down much later, so take that as you will. According to this account, the Baekje envoys who transmitted the first Buddha image to Japan stopped for a while on Tsushima before proceeding on to the Yamato court. While they were there, the monks who were looking after the image built a small building in which to conduct their daily rituals, effectively building the first Buddhist place of worship in the archipelago. A temple was later said to have been built on that spot, and in the mid-15th century it was named Bairinji. While the narrative is highly suspect, there is some evidence that the area around Bairinji was indeed an important point on the island. Prior to the digging of the two channels to connect the east and west coasts, the area near Bairinji, known as Kofunakoshi, or the small boat portage, was the narrowest part of Tsushima, right near the middle, where Aso Bay and Mitsuura Bay almost meet. We know that at least in the 9th century this is where envoys would disembark from one ship which had brought them from the archipelago, and embark onto another which would take them to the continent, and vice versa. Likewise, their goods would be carried across the narrow strip of land. This was like a natural barrier and an ideal location for an official checkpoint, and in later years Bairinji temple served as this administrative point, providing the necessary paperwork for crews coming to and from Japan, including the various Joseon dynasty missions in the Edo period.

Why this system of portage and changing ships, instead of just sailing around? Such a system was practical for several reasons. For one, it was relatively easy to find Tsushima from the mainland. Experienced ships could sail there, transfer cargo to ships experienced with the archipelago and the Seto Inland Sea, and then return swiftly to Korea. Furthermore, this system gave Yamato and Japan forewarning, particularly of incoming diplomatic missions. No chance mistaking ships for an invasion or pirates of some kind, as word could be sent ahead and everything could be arranged in preparation for the incoming mission. These are details that are often frustratingly left out of many of the early accounts, but there must have been some logistics to take care of things like this.

Whether or not Bairinji’s history actually goes back to 538, it does have claim to some rather ancient artifacts, including a 9th century Buddha image from the Unified, or Later, Silla period as well as 579 chapters of the Dai Hannya Haramitta Kyo, or the Greater Perfection of Wisdom Sutra, from a 14th century copy. These were actually stolen from the temple in 2014, but later recovered. Other statues were stolen two years previously from other temples on Tsushima, which speaks to some of the tensions that still exist between Korea and Japan. Claims were made that the statues had originally been stolen by Japanese pirates, or wakou, from Korea and brought to Japan, so the modern-day thieves were simply righting an old wrong. However, Korean courts eventually found that the items should be returned to Japan, though there were those who disagreed with the ruling. This is an example of the ongoing tensions that can sometimes make study of inter-strait history a bit complex.

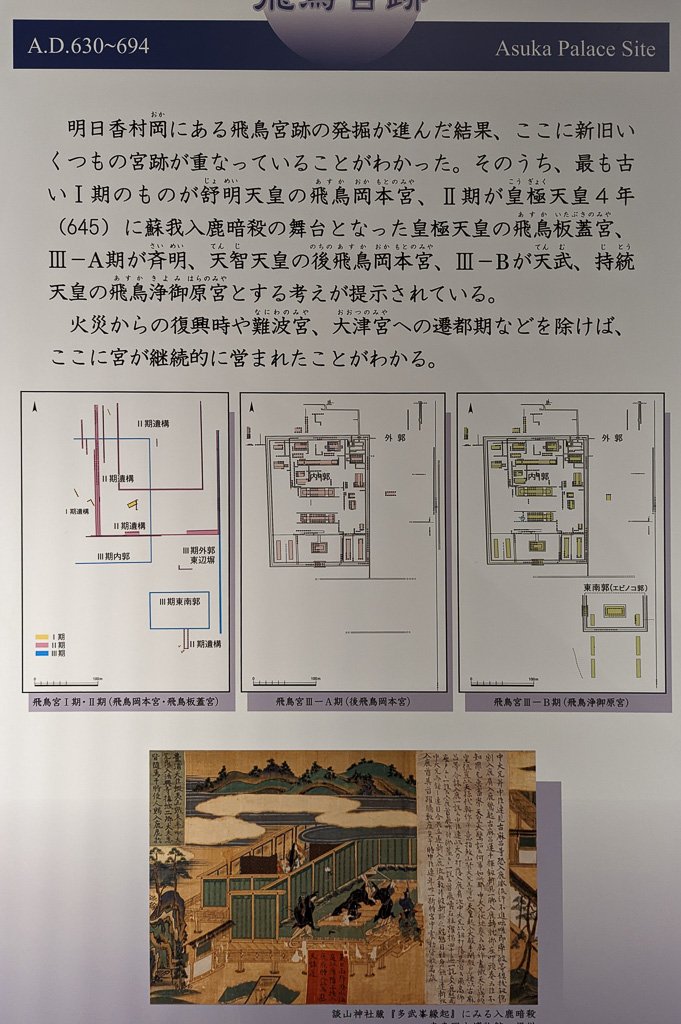

More concrete than the possible location of a theoretical early worship structure are the earthworks of Kaneda fortress. This is a mid-7th century fort, created by Yamato to defend itself from a presumed continental invasion. We even have mention of it in the Nihon Shoki. It appears to have been repaired in the late 7th century, and then continued to be used until some time in the 8th century, when it was abandoned, seeing as how the invasion had never materialized, and no doubt maintaining the defenses on top of a mountain all the way out on Tsushima would have been a costly endeavor.

Over time the name “Kaneda” was forgotten, though the stone and earthworks on the mountain gave the site the name “Shiroyama”, or Castle Mountain, at least by the 15th century. In the Edo period, scholars set out trying to find the Kaneda fortress mentioned in the Nihon Shoki, and at one point identified this with an area known as Kanedahara, or Kaneda Fields, in the modern Sasu district, on the southwest coast of Tsushima. However, a scholar named Suyama Don’ou identified the current mountaintop site, which has generally been accepted as accurate. The earthworks do appear to show the kind of Baekje-style fortifications that Yamato built at this time, which took advantage of the natural features of the terrain. These fortresses, or castles, were more like fortified positions—long walls that could give troops a secure place to entrench themselves. They would not have had the impressive donjon, or tenshukaku, that is the most notable feature of of later Japanese and even European castles.

Most of the Baekje style castles in Japan are primarily earthworks—for example the Demon’s castle in modern Okayama. Kaneda is unique, though, with about 2.8 kilometers of stone walls, most of which are reportedly in quite good condition. There were three main gates and remains of various buildings have been determined from post-holes uncovered on the site. There is a name for the top of the mountain, Houtateguma, suggesting that there may have once been some kind of beacon tower placed there with a light that could presumably be used to signal to others, but no remains have been found.

The defensive nature of the position is also attested to in modern times. During the early 20th century, the Japanese military placed batteries on the fortress, and an auxiliary fort nearby. These constructions damaged some of the ancient walls, but this still demonstrates Tsushima’s place at the edge of Japan and the continent, even into modern times.

For all that it is impressive, I have to say that we regrettably did not make it to the fortress, as it is a hike to see everything, and our time was limited. If you do go, be prepared for some trekking, as this really is a fortress on a mountain, and you need to park and take the Kaneda fortress trail up.

Moving on from the 8th century, we have evidence of Tsushima in written records throughout the next several centuries, but there isn’t a lot clearly remaining on the island from that period—at least not extant buildings. In the records we can see that there were clearly things going on, and quite often it wasn’t great for the island. For instance, there was the Toi Invasion in the 11th century, when pirates—possibly Tungusic speaking Jurchen from the area of Manchuria—invaded without warning, killing and taking people away as slaves. It was horrific, but relatively short-lived, as it seems that the invaders weren’t intent on staying.

Perhaps a more lasting impression was made by the invasions of the Mongols in the 13th century. This is an event that has been hugely impactful on Japan and Japanese history. The first invasion in 1274, the Mongols used their vassal state of Goryeo to build a fleet of ships and attempted to cross the strait to invade Japan. The typical narrative talks about how they came ashore at Hakata Bay, in modern Fukuoka, and the Kamakura government called up soldiers from across the country to their defense. Not only that, but monks and priests prayed for divine intervention to protect Japan. According to the most common narrative, a kamikaze, or divine wind, arose in the form of a typhoon that blew into Hakata Bay and sank much of the Mongol fleet.

That event would have ripple effects throughout Japanese society. On the one hand, the Mongols brought new weapons in the form of explosives, and we see changes in the arms of the samurai as their swords got noticeably beefier, presumably to do better against similarly armored foes. The government also fortified Hakata Bay, which saw another attack in 1281, which similarly failed.

Though neither attempted invasion succeeded, both were extremely costly. Samurai who fought for their country expected to get rewarded afterwards, and not just with high praise. Typically when samurai fought they would be richly rewarded by their lord with gifts taken from the losing side, to include land and property. In the case of the Mongols, however, there was no land or property to give out. This left the Kamakura government in a bit of a pickle, and the discontent fomented by lack of payment is often cited as one of the key contributors to bringing down the Kamakura government and leading to the start of the Muromachi period in the 14th century.

The invasions didn’t just appear at Hakata though. In 1274, after the Mongol fleet first left Goryeo on the Korean Peninsula, they landed first at Tsushima and then Iki, following the traditional trade routes and killing and pillaging as they went. In Tsushima, the Mongol armies arrived in the south, landing at Komoda beach near Sasuura. Lookouts saw them coming and the So clan hastily gathered up a defense, but it was no use. The Mongol army established a beachhead and proceeded to spend the next week securing the island. From there they moved on to Iki, the next island in the chain, and on our journey. Countless men and women were killed or taken prisoner, and when the Mongols retreated after the storm, they brought numerous prisoners back with them.

Although the Mongols had been defeated, they were not finished with their plans to annex Japan into their growing empire. They launched another invasion in 1281, this time with reinforcements drawn from the area of the Yangtze river, where they had defeated the ethnic Han Song dynasty two years prior. Again, they landed at Tsushima, but met fierce resistance—the government had been preparing for this fight ever since the last one. Unfortunately, Tsushima again fell under Mongol control, but not without putting up a fight. When the Mongols were again defeated, they left the island once again, this time never to return.

If you want to read up more on the events of the Mongol Invasion, I would recommend Dr. Thomas Conlan’s book, “No Need for Divine Intervention”. It goes into much more detail than I can here.

These traumatic events have been seared into the memories of Tsushima and the nearby island of Iki. Even though both islands have long since rebuilt, memories of the invasion are embedded in the landscape of both islands, and it is easy to find associated historical sites or even take a dedicated tour. In 2020, the events of the invasion of Tsushima were fictionalized into a game that you may have heard of called Ghost of Tsushima. I won’t get into a review of the game—I haven’t played it myself—but many of the locations in the game were drawn on actual locations in Tsushima. Most, like Kaneda Castle, are fictionalized to a large extent, but it did bring awareness to the island, and attracted a large fan base. Indeed, when we picked up our rental car, the helpful staff offered us a map with Ghost of Tsushima game locations in case we wanted to see them for ourselves.

As I noted, many of the places mentioned in the game are highly fictionalized, as are many of the individuals and groups—after all, the goal is to play through and actually defeat the enemies, and just getting slaughtered by Mongols and waiting for them to leave wouldn’t exactly make for great gameplay. Shrines offer “charms” to the user and so finding and visiting all of the shrines in the in-game world becomes a player goal. And so when fans of the game learned that the torii gate of Watatsumi Shrine, one of the real-life iconic shrines in Tsushima, was destroyed by a typhoon in September of 2020, about a month after the game was released, they came to its aid and raised over 27 million yen to help restore the torii gates. A tremendous outpouring from the community.

And while you cannot visit all of the locations in the game, you can visit Watazumi Shrine, with its restored torii gates that extend into the water.

Watatsumi Shrine itself has some interesting, if somewhat confusing, history. It is one of two shrines on Tsushima that claim to be the shrine listed in the 10th-century Engi Shiki as “Watatsumi Shrine”. This is believed to have been the shrine to the God of the Sea, whose palace Hiko Hoho-demi traveled down to in order to find his brother’s fishhook—a story noted in the Nihon Shoki and which we covered in episode 23. Notwithstanding that most of that story claims it was happening on the eastern side of Kyushu, there is a local belief that Tsushima is actually the place where that story originated.

The popular shrine that had its torii repaired is popularly known as Watatsumi Shrine, today. The other one is known as Kaijin Shrine, literally translating to the Shrine of the Sea God, and it is also known as Tsushima no kuni no Ichinomiya; That is to say the first, or primary, shrine of Tsushima. Some of the confusion may come as it appears that Kaijin shrine was, indeed, the more important of the two for some time. It was known as the main Hachiman shrine in Tsushima, and may have been connected with a local temple as well. It carries important historical records that help to chart some of the powerful families of Tsushima, and also claims ownership of an ancient Buddhist image from Silla that was later stolen. In the 19th century it was identified as the Watatsumi Shrine mentioned in the Engi Shiki, and made Toyotama Hime and Hikohohodemi the primary deities worshipped at the shrine, replacing the previous worship of Hachiman.

Shrines and temples can be fascinating to study, but can also be somewhat tricky to understand, historically. Given their religious nature, the founding stories of such institutions can sometimes be rather fantastical, and since they typically aren’t written down until much later, it is hard to tell what part of the story is original and what part has been influenced by later stories, like those in the Nihon Shoki or the Kojiki.

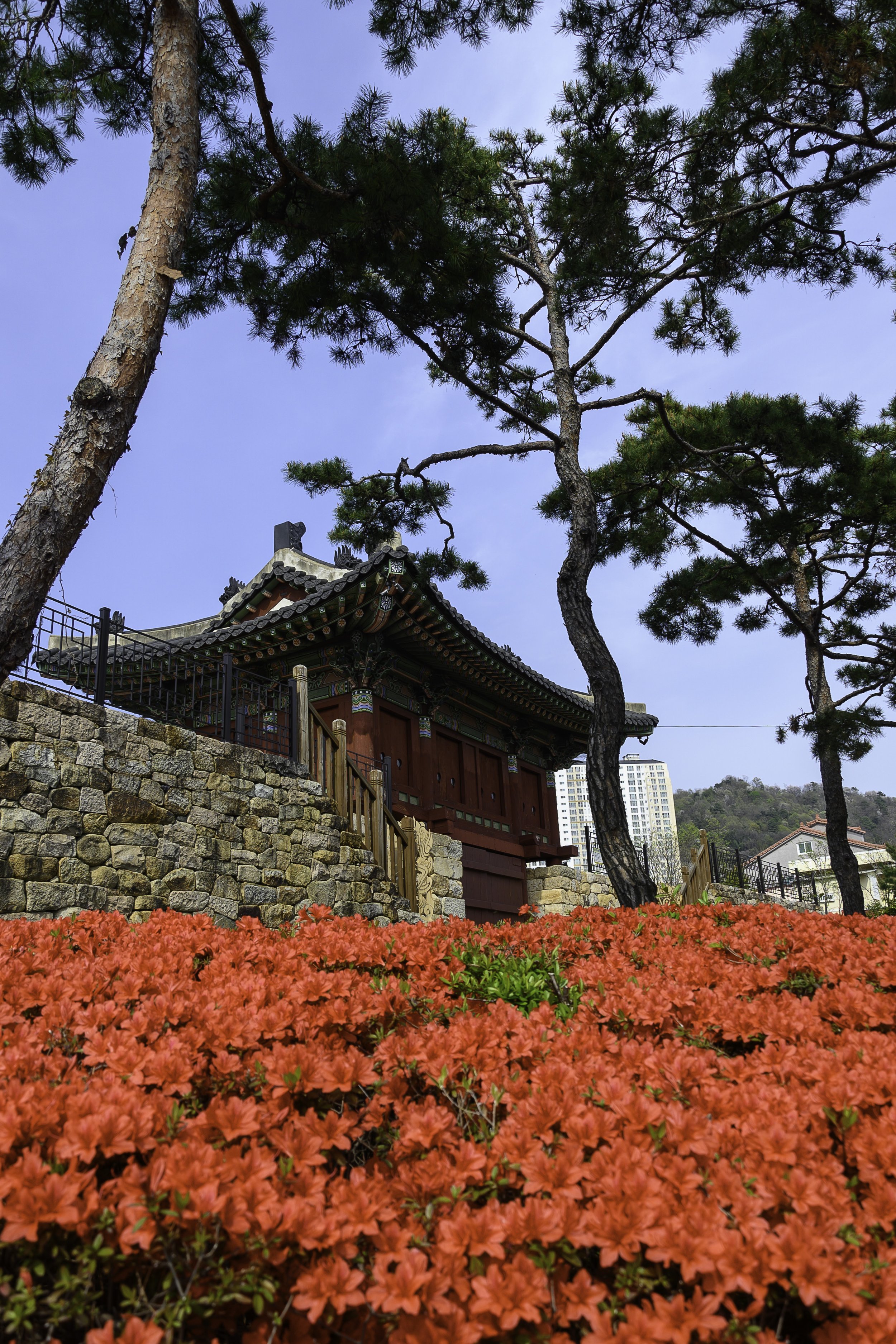

Another interesting example of a somewhat unclear history is that of the Buddhist temple, Kokubun-ji. Kokubunji are provincial temples, originally set up inthe decree of 741 that had them erected across the archipelago, one in each province at the time, in an attempt to protect the country from harm, Knowing the location of a Kokubunji can therefore often tell you something about where the Nara era provincial administration sat, as it would likely have been nearby. In many cases, these were probably connected to the local elite, as well.

This is not quite as simple with Tsushima Kokubun-ji. While it was originally designated in the decree of 741, a later decree in 745 stated that the expenses for these temples would come directly out of tax revenues in the provinces, and at that time Tsushima was excluded. Moreover, the Kokubunji on nearby Iki island was funded by taxes from Hizen province. So it isn’t until 855 that we have clear evidence of an early provincial temple for Tsushima, in this case known as a Tobunji, or Island Temple, rather than a Kokubunji.

The location of that early temple is unknown, and it burned down only two years later when Tsushima was attacked by forces from Kyushu. It is unclear what happened to it in the following centures, but by the 14th or 15th century it was apparently situated in Izuhara town, near the site of what would become Kaneishi Castle. It was later rebuilt in its current location, on the other side of Izuhara town. It burned down in the Edo period—all except the gate, which was built in 1807. This gate is at least locally famous for its age and history. It was also the site of the guesthouses for the 1811 diplomatic mission from Joseon—the dynasty that followed Koryeo.

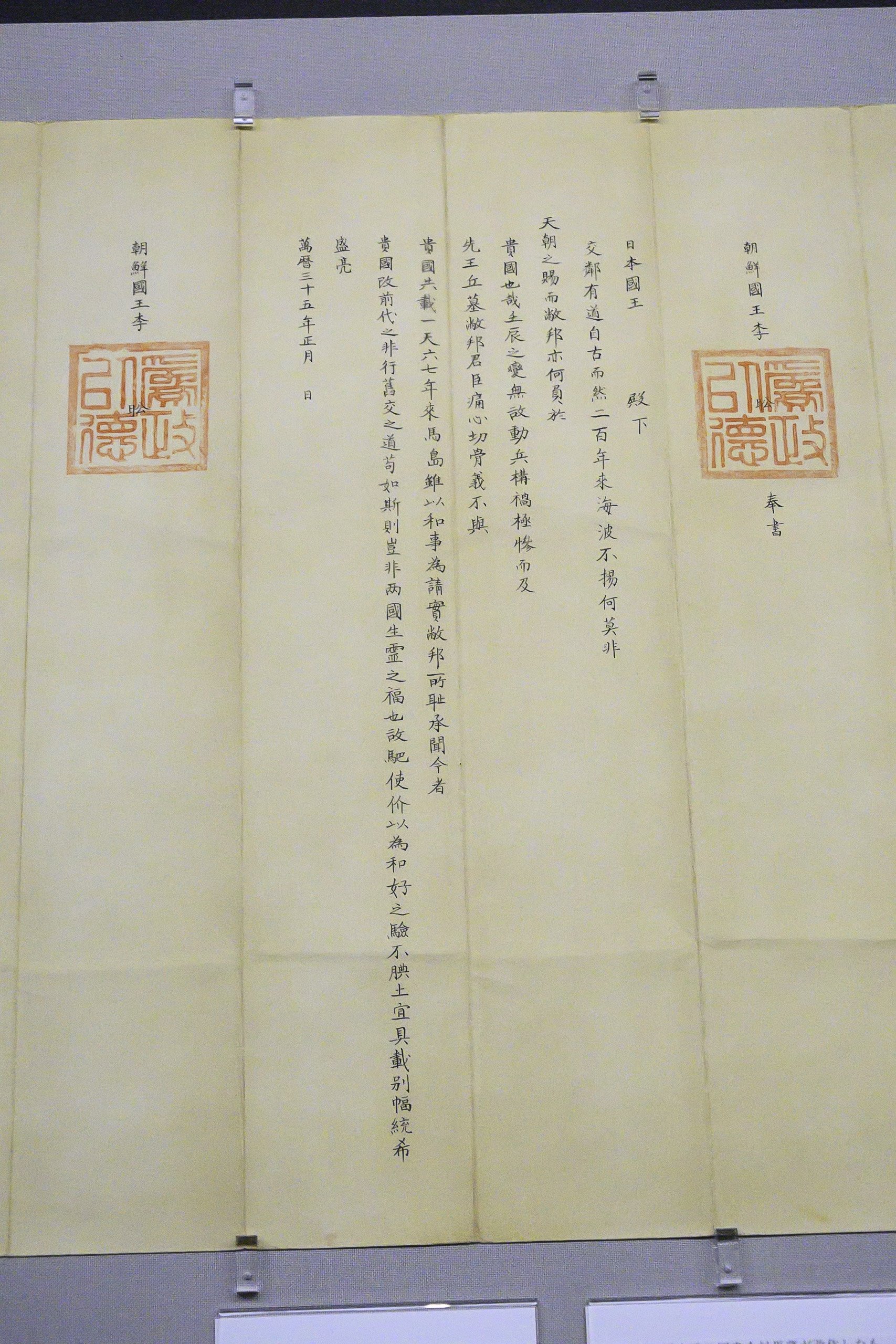

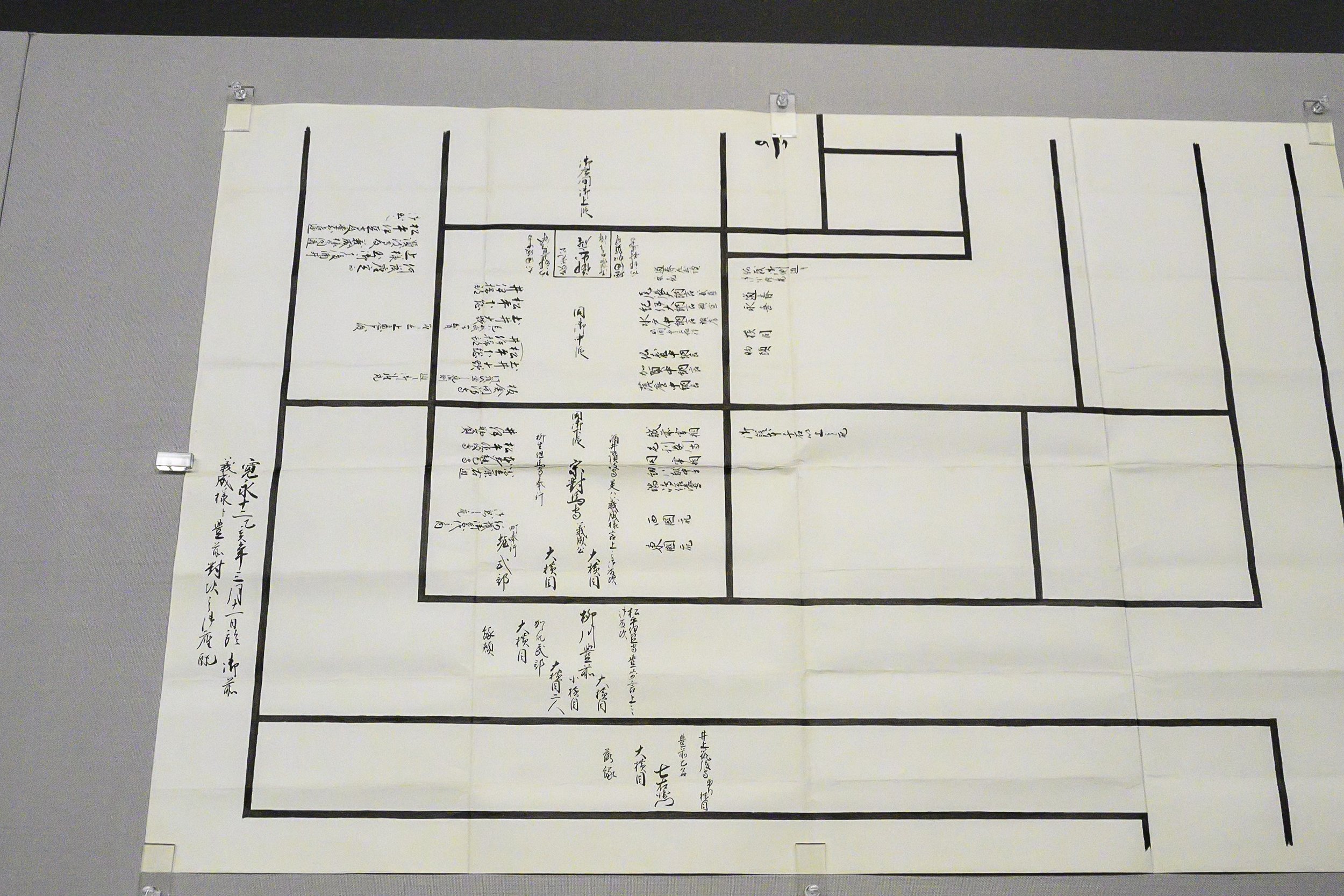

Those missions are another rather famous part of the history of Tsushima, which, as we’ve seen, has long been a gateway between the archipelago and the peninsula. In the Edo period, there were numerous diplomatic missions from the Joseon dynasty to the Tokugawa shogunate, and these grand affairs are often touted in the history of Tsushima, with many locations specifically calling out the island’s deep involvement in cross-strait relations. Relations which, to really understand, we need to probably start with a look at the famous (or perhaps even infamous) Sou clan.

The Sou clan became particularly influential in Tsushima in the 13th century. The local officials, the Abiru clan, who had long been in charge of the island, were declared to be in rebellion against the Dazaifu, and so Koremune Shigehisa was sent to quell them. In return, he was made Jito, or land steward, under the Shoni clan, who were the Shugo of Chikuzen and Hizen, including the island of Tsushima. The Sou clan, descendents of the Koremune, ruled Tsushima ever since, first as vassals of the Shoni , but eventually they ran things outright.

Thus, Sou Sukekuni was in charge when the Mongols invaded in 1274. Despite having only 80 or so mounted warriors under his charge, he attempted to defend the island, dying in battle. Nonetheless, when the Mongols retreated, the Sou family retained their position. Later, they supported the Ashikaga in their bid to become shogun, and were eventually named the Shugo of Tsushima, a title they kept until the Meiji period.

As we’ve mentioned, despite its size, Tsushima is not the most hospitable of locations. It is mountainous, with many bays and inlets, making both cross-land travel and agriculture relatively difficult. And thus the Sou clan came to rely on trade with the continent for their wealth and support. Although, “trade” might be a bit negotiable.

Remember how the early Japanese regularly raided the coast of the peninsula? It was frequent enough that a term arose—the Wakou, the Japanese invaders, or Japanese pirates. In fact, the term “wakou” became so synonymous with piracy that almost any pirate group could be labeled as “wakou”, whether Japanese or not. Some of them that we know about were downright cosmopolitan, with very diverse crews from a variety of different cultures.

Given its position, the rough terrain, and myriad bays that could easily hide ships and other such things, Tsushima made a great base for fishermen-slash-pirates to launch from. Particularly in harsh times, desperate individuals from Tsushima and other islands might take their chances to go and raid the mainland.

In the early 15th century, the new Joseon dynasty had had enough. They sent an expeditionary force to Tsushima to put an end to the wakou. The expedition came in 1419. The year before, the head of the Sou clan, Sou Sadashige, had died. His son, Sou Sadamori, took his place, but had not yet come of age, leaving actual power in the hands of Souda Saemontarou, leader of the Wakou pirates.

Eventually the Joseon forces were defeated by the forces of Tsushima, including the wakou. The Joseon court considered sending another punitive expedition, but it never materialized. What did eventually happen, though, was, oddly, closer ties between the peninsula and Tsushima. Sou Sadamori, who grew up in that tumultuous time, worked to repair relationships with the Joseon court, concluding a treaty that that allowed the Sou clan to basically monopolize trade with the Korean peninsula. Treaty ports on the peninsula began to attract permanent settlements of Japanese merchants, and these “wakan”, or Japanese districts, came nominally under the jurisdiction of the Sou of Tsushima.

The Sou clan maintained their place as the intermediaries with the Joseon state through the 16th century. Messages sent from the Japanese court to Joseon would be sent to the Sou, who would deliver them to the Joseon court, and in turn handle all replies from the peninsula back to the Japanese mainland. And this over time led them to develop some, shall we say, special techniques to make sure these exchanges were as fruitful as possible.

You see, the treaties with the Joseon court only allowed fifty ships a year from Tsushima to trade with the peninsula. But since all of the documents flowed through the Sou, they had plenty of time to study the seals of both courts—those of the Joseon kingdom and those of Japan – and have fake seals created for their own ends. In part through the use of these fake seals, the Sou clan were able to pretend their ships were coming from other people—real or fake—and thus get around the 50 ship per year limit. They also used them in other ways to try and maintain their position between the two countries.

All of this came to a head when the Taikou, Toyotomi Hideyoshi, began to dream of continental conquest. Hideyoshi, at this point the undeniable ruler of all of Japan, had a bit of an ego—not exactly undeserved, mind you. His letter to the Joseon king Seongjo, demanding submission, was quite inflammatory, and the Sou clan realized immediately that it would be taken as an insult. Not only could it jeopardize relations with the continent, it could also jeopardize their own unique status. Which is why they decided to modify it using what in modern computer hacker terms might be called a man-in-the-middle attack – which, with their fake seal game, they had plenty of experience with. The Sou were able to modify the language in each missive to make the language more acceptable to either side. They also dragged their feet in the whole matter, delaying things for at least two years

But Hideyoshi’s mind was set on conquest. Specifically, he had ambitions of displacing the Ming dynasty itself, and he demanded that the Joseon court submit and allow the Japanese forces through to face the Ming dynasty. The Joseon refused to grant his request, and eventually Hideyoshi had enough. He threatened an invasion of Korea if the Joseon dynasty didn’t capitulate to his requests.

Throughout this process, the Sou attempted to smooth things over as best they could. However, even they couldn’t forge the words presented by a face-to-face envoy, nor could they put off Hideyoshi’s anger forever. And thus Tsushima became one of the launching off points for the Japanese invasions of Korea in 1592 and again in 1597. Tsushima, along with nearby Iki, would have various castles built to help supply the invading forces. One such castle was the Shimizuyama-jo, overlooking the town of Izuhara. Some of the walls and earthworks can still be seen up on the mountain overlooking the town, and there are trails up from the site of Kaneishi castle, down below.

Both of these invasions ultimately failed, though not without a huge loss of life and destruction on the peninsula—a loss that is still felt, even today.

The second and final invasion ended in 1598. Both sides were exhausted and the Japanese were losing ground, but the true catalyst, unbeknownst to those on the continent, was the death of Hideyoshi. The Council of Regents, a group of five daimyo appointed to rule until Hideyoshi’s son, Hideyori, came of age kept Hideyoshi’s death a secret to maintain morale until they could withdraw from the continent.

With the war over, the Sou clan took the lead in peace negotiations with the Joseon court, partly in an attempt to reestablish their position and their trade. In 1607, after Tokugawa had established himself and his family as the new shogunal line, the Sou continued to fake documents to the Joseon court, and then to fake documents right back to the newly established bakufu so that their previous forgeries wouldn’t be uncovered. This got them in a tight spot.

In the early 1600s, one Yanagawa Shigeoki had a grudge to settle with Sou Yoshinari, and so he went and told the Bakufu about the diplomatic forgeries that the Sou had committed, going back years. Yoshinari was summoned to Edo, where he was made to answer the allegations by Shigeoki. Sure enough, it was proven that the Sou had, indeed, been forging seals and letters, but after examination, Tokugawa Iemitsu, the third Tokugawa Shogun, decided that they had not caused any great harm—in fact, some of their meddling had actually helped, since they knew the diplomatic situation with the Joseon court better than just about anyone else, and they clearly were incentivized to see positive relations between Japan and Korea. As such, despite the fact that he was right, Yanagawa Shigeoki was exiled, while the Sou clan was given a slap on the wrist and allowed to continue operating as the intermediaries with the Joseon court.

There was one caveat, however: The Sou clan would no longer be unsupervised. Educated monks from the most prestigious Zen temples in Kyoto, accredited as experts in diplomacy, would be dispatched to Tsushima to oversee the creation of diplomatic documents and other such matters, bringing the Sou clan’s forgeries to a halt.

Despite that, the Sou clan continued to facilitate relations with the peninsula, including some twelve diplomatic missions from Korea: the Joseon Tsuushinshi. The first was in 1607, to Tokugawa Hidetada, and these were lavish affairs, even more elaborate than the annual daimyo pilgrimages for the sankin-kotai, or alternate attendance at Edo. The embassies brought almost 500 people, including acrobats and other forms of entertainment. Combined with their foreign dress and styles, it was a real event for people whenever they went.

Today, these Tsuushinshi are a big draw for Korean tourists, and just about anywhere you go—though especially around Izuhara town—you will find signs in Japanese, Korean, and English about locations specifically associated with these missions. And in years past, they’ve even reenacted some of the processions and ceremonies.

Speaking of Izuhara, this was the castle town from which the Sou administered Tsushima. Banshoin temple was the Sou family temple, and contains the graves of many members of the Sou family. In 1528, the Sou built a fortified residence in front of Banshoin, and eventually that grew into the castle from which they ruled Tsushima. Today, only the garden and some of the stone walls remain. The yagura atop the main gate has been rebuilt, but mostly it is in ruins. The Tsushima Museum sits on the site as well. Nearby there is also a special museum specifically dedicated to the Tsuushinshi missions.

Izuhara town itself is an interesting place. Much of what you see harkens back to the Edo period. Much like Edo itself, the densely packed wood and paper houses were a constant fire hazard, and there were several times where the entire town burned to the ground. As such they began to institute firebreaks in the form of stone walls which were placed around the town to help prevent fire from too quickly spreading from one house to the next. This is something that was instituted elsewhere, including Edo, but I’ve never seen so many extant firewalls before, and pretty soon after you start looking for them, you will see them everywhere.

The area closest to the harbor was an area mostly for merchants and similar working class people, and even today this can be seen in some of the older buildings and property layouts. There are also a fair number of izakaya and various other establishments in the area. Further inland you can find the old samurai district, across from the Hachiman shrine. The houses and the gates in that area are just a little bit nicer. While many modern buildings have gone up in the town, you can still find traces of the older buildings back from the days of the Sou clan and the Korean envoys.

Today, Izuhara is perhaps the largest town on Tsushima, but that isn’t saying much—the population of the entire island is around 31,000 people, only slightly larger than that of nearby Iki, which is only about one fifth the size of Tsushuma in land area. From Izuhara, you can catch a ferry to Iki or all the way to Hakata, in Fukuoka. You can also always take a plane as well.

Before leaving Tsushima, I’d like to mention one more thing—the leopard cat of Tsushima, the Yamaneko. This has become something of a symbol in Tsushima, but unfortunately it is critically endangered, at least on the island itself. It is all but gone from the southern part of Tsushima—human encroachment on its habitat has been part of the issue, but so has the introduction of domesticated cats. The yamaneko itself is about the size of a typical housecat, and might be mistaken for one, though it has a very distinctive spotted appearance. Domesticated cats have been shown to outcompete their wild cousins, while also passing on harmful diseases, which also affect the population. Just about everywhere you go you’ll see signs and evidence of this special cat. There is also a breeding program in the north if you want to see them for yourself. Even the small Tsushima Airport is named Yamaneko Airport, and the single baggage claim features a whole diorama of little plush leopard cats wearing traditional clothing and waving hello to new arrivals.

If you like rugged coastlines, fascinating scenery, and the odd bit of history thrown in, might I suggest taking a look at Tsushima, the border island between Japan and Korea.

We only had a few days, but it was a truly wonderful experience. Next up we caught the ferry to Iki island, the site of the ancient Iki-koku, possibly represented by the Yayoi era Harunotsuji site. Of all the places I’ve been so far, this is second only to Yoshinogari in the work and reconstruction they’ve done. They’ve even discovered what they believe to be an ancient dock or boat launch. But we’ll cover that next week, as we continue on our self-guided Gishiwajinden tour.

Until then, thank you for listening and for all of your support.

If you like what we are doing, tell your friends and feel free to rate us wherever you listen to podcasts. If you feel the need to do more, and want to help us keep this going, we have information about how you can donate on Patreon or through our KoFi site, ko-fi.com/sengokudaimyo, or find the links over at our main website, SengokuDaimyo.com/Podcast, where we will have some more discussion on topics from this episode.

Also, feel free to reach out to us at our Sengoku Daimyo Facebook page. You can also email us at the.sengoku.daimyo@gmail.com.

Thank you, also, to Ellen for their work editing the podcast.

And that’s all for now. Thank you again, and I’ll see you next episode on Sengoku Daimyo’s Chronicles of Japan.

References

Conlan, Thomas. (2001). In little need of divine intervention : Takezaki Suenaga's scrolls of the Mongol invasions of Japan. Ithaca, N.Y. :East Asia Program, Cornell University,

Aston, W. G. (1972). Nihongi, chronicles of Japan from the earliest times to A.D. 697. London: Allen & Unwin. ISBN0-80480984-4