Previous Episodes

- May 2025

- April 2025

- March 2025

- February 2025

- January 2025

- December 2024

- November 2024

- October 2024

- September 2024

- August 2024

- July 2024

- June 2024

- May 2024

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

This episode we say goodbye to Wohodo and say hello to his successor, Magari no Ōye, aka Magari no Ohine.

On Succession

We’ve talked in the past about succession and the Chronicles’ conception of what was appropriate. In that formula, only the son of the current sovereign and the designated Queen was considered a viable candidate for the throne, and a Queen wasn’t just the wife of the sovereign. The Queen had to be specifically designated as such and they had to be of royal descent themselves.

There is no evidence that I see which directly suggests that Menoko had those qualifications in the Chroniclers’ eyes. Rather, they clearly see Tashiraga no Iratsume as the One True Queen. Nonetheless, where they could have easily erased Prince Ohine and his brother from the record, they did not. They left them in, albeit with short reigns—possibly an accurate reflection of the time.

Some later sources put Tashiraga’s son, the future sovereign known as Kimmei, aka Ame Kunioshi Hiraki Hiro Niwa, as the direct inheritor from his father, Wohodo, aka Keitai. There are even some clues, hidden though they may be, that Ame Kunioshi had his two elder brothers killed in a struggle that the Chroniclers chose not to report for some reason.

The Nihon Shoki makes the claim, of course, that Ame Kunioshi was simply too young, and that he hadn’t come of age. This seems a bizarre claim given that they count Homuda Wake as sovereign from the time he was about 3 years old. Granted, much of Homuda’s story has more than a little of the fantastical about it, and so the veracity of that claim is questionable, but still it is left in without comment by the Chroniclers. Why would they not have commented on that?

This is a thread we’ll continue to pull on as we move closer to Ame Kunioshi’s assumption of the throne.

Miyake (屯倉) - The Royal Granaries

These are often translated as the Royal (or Imperial) Granaries or something similar, though there is no direct account of just what it was and what they were like. Many assume, however, that they were an early form of local governance set up by Yamato—and possibly others—in more far flung territory.

As seen above, the idea of storehouses appears in the archaeological record from at least the Yayoi period. Early raised structures were likely places to store grain where vermin could not easily get to it and it kept things dry.

Storehouses were a common good for a village. We see don’t see a storehouse attached to every household, so they were likely shared resources. But as states started to form, it wasn’t just villages and surrounding farms. Rice was the currency of the day, and taxes—largely rice, but likely other commodities as well—would be collected in central locations run by the central government. Essentially these would be local tax centers.

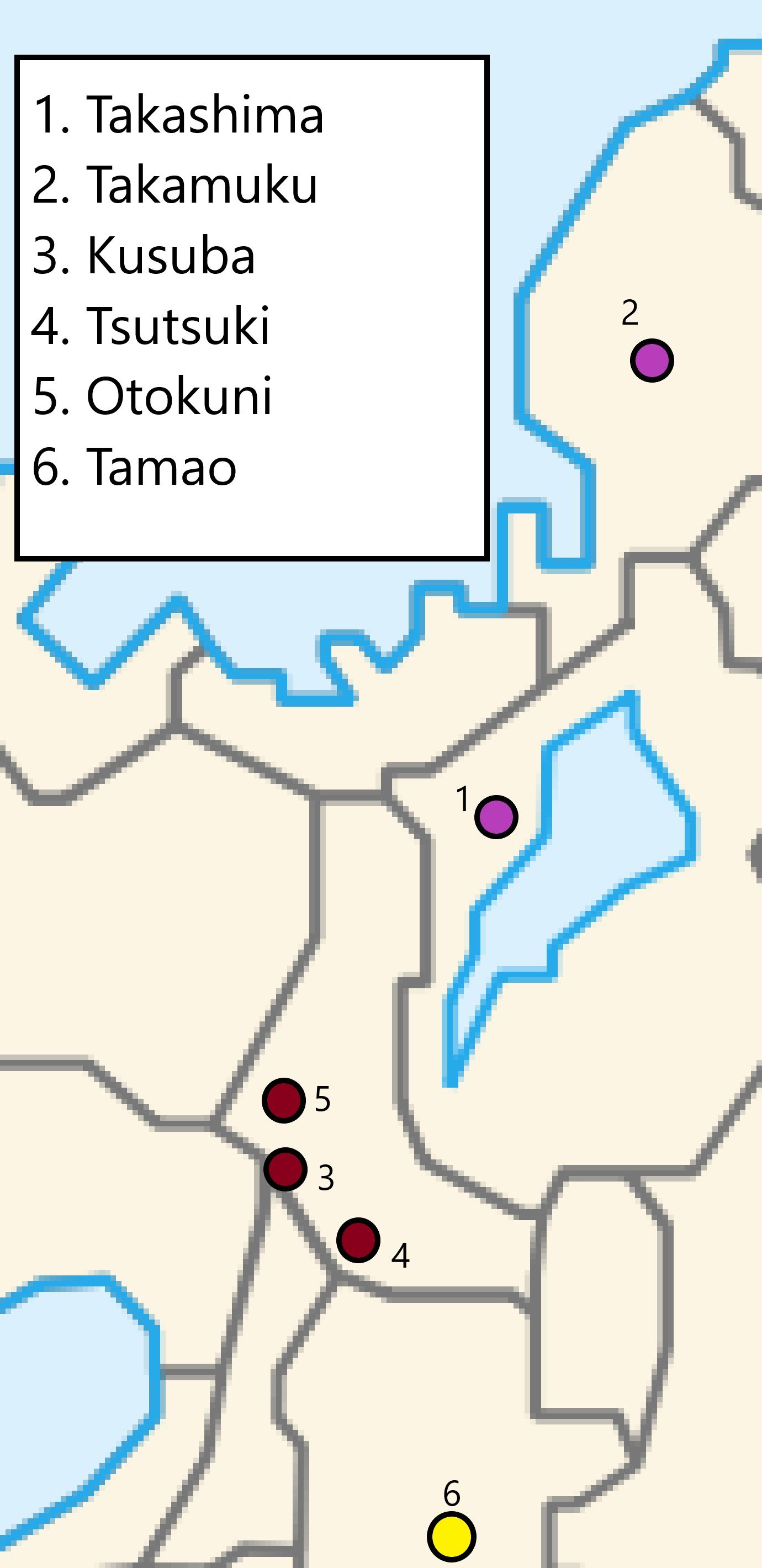

This could be what the structures in Osaka, pictured at the top of this post, were for. There were at least 10 of them, and it may be that they were the local center both taking in rice and distributing it when necessary. It is also possible, seeing that this was in Naniwa during the time when the ancient court is said to have been there, that these represent the endpoint of a network of storehouses.

That appears to have been the function of the “miyake”, which oversaw selected acreage of rice-land and the income that the state demanded. Based on later examples, we can make an assumption that local administrators would likely set the amount of rice to be collected and take a cut of the collected rice for operating the miyake itself. This would be some amount over what the court expected to receive.

Furthermore, these miyake didn’t collect generic tax revenue. Rather, the revenue generated by the miyake was designated to specific purposes or even to specific persons. So you might have land for the upkeep of the Queen’s quarters, or even for maintaining a particular kofun. In other cases you might have land that is designated for the use of a given noble or official, so that they could live in a style appropriate to their position.

In the brief reign of Ohine, aka Ankan Tenno, we see the largest number of miyake mentioned—more than during any other reign. They are occasionally mentioned elsewhere, but not nearly so heavily, let alone so many in the course of one or two years. While the language in the Nihon Shoki can make it seem as if the miyake were, in many cases, previously extant and simply repurposed, I suspect that in many, if not most, cases this is the point of their effective creation.

Generally speaking, these are miyake that are being created for the benefit of members of the royal family, which is effectively the court. It demonstrates a way that the court was further expanding its administrative and bureaucratic structures, much as the creation of the Be had similar effects. Later, provincial governance would be further structured and organized.

Another aspect we see here is the assertion of royal prerogative over any and all land. The ability to assign or re-assign land and titles is a key lever of power by which the sovereign and the court could require compliance. Now, how this worked in actual practice vice tentative legal theory is another question altogether. I suspect that such things would have to be reinforced from time to time with actual violence, rather than just threats of removing land or title.

-

Welcome to Sengoku Daimyo’s Chronicles of Japan. My name is Joshua and this is Episode 78: Imminent Domain in Ancient Japan

First off, a huge shout out to listener, Zach. When I asked everyone about suggestions for transcripts, he went out and found a tool to auto-generate them, tried it out already, and sent me example results. So I’ll be going over the tool and seeing what I can do to get transcripts uploaded for the podcast, hopefully making everything a bit more accessible. Thanks again, Zach!

Second, I want to address the way “Keitai” (as in Keitai Tennou, the first sovereign of this current dynasty) reminds me of “keitai” as in “keitai denwa”, or “cell phone”. This leads to some interesting notes on Japanese language, especially for those of us coming at it from outside. While both of those words sound the same to my English-speaking ear, especially in an English sentence, and are spelled the same in hiragana, they are slightly different, and as a Japanese instructor recently pointed out to me, they don’t sound the same in Japanese. This has to do with a certain tonal quality to Japanese that isn’t typically taught, and it is almost more about the difference between accents than anything else. In fact, there are even regional differences, all having to do with tone.

Or perhaps, more precisely, having to do with pitch. As one listener pointed out, this is more properly referred to as a “pitch accent”, and falls somewhere between a truly tonal language, like Putonghua, aka Mandarin, or the Thai language, and a stress-accented language like English and most European languages.

As an example, take the word “ame”. It can mean “rain” or it can mean “candy”, depending on the tone you use. Back when I was studying in Japan, I knew a couple who were from different parts of Japan, and the wife had a bit of an accent. She would say “ame ga furu”—the rain is falling—and her children would laugh because, as they had been brought up, it sounded like “ame ga furu”—candy is falling from the sky. Now, obviously they knew what she was saying, so if you don’t hear a difference, don’t worry, you will probably still be understood. Nonetheless, I think it is a curious feature of Japanese that often doesn’t get mentioned that these sorts of things exist, and I thought this might be a good time to share.

So, for anyone else who thinks I overreached in seeing Keitai Tennou as the cellphone sovereign, you just might be correct. I’m still going to giggle a little bit when I hear it though.

Anyway, back to history.

The last few episodes have been covering the reign of Wohodo no Ohokimi in the beginning of the 6th century, and today we’ll wrap up his reign and talk about his successors. To recap: Wohodo is said to have come to the throne in 507 and reigned up until his death in either 531 or 534. His ascension is strange—with the death of Wohatsuse, aka Buretsu Tennou, without any heirs the court scoured the land for a suitable candidate. They claim that Wohodo was a descendant of Homuda Wake, aka Oujin Tennou, some 5 generations back, and even descended from Ikume Iribiko through his maternal line. However accurate this was, it is clear that the line of Ohosazaki, aka Nintoku Tennou, the sovereigns responsible for the giant keyhole tumuli in the Kawachi region, such as Daisen Ryo, had come to an end with Wohatsuse—at least along the paternal line. So Wohodo had to be brought in from the distant land of Kochi, on the Japan Sea side of central to eastern Honshuu.

This raises some interesting questions about the relationship between Yamato and other Wa polities in Japan. Some scholars have suggested that Wohodo was a part of a separate royal family in Kochi—that many of the regions, including Izumo, Kibi, and Northern Kyushu all had their own independent polities that were only loosely tied to Yamato, which may have been primus inter pares—first among equals. It is also possible by this time that Yamato had some kind of a paramountcy; that is to say that they had become central enough that the other states were not seen as equals. Still, local governance would have more directly revolved around the local chieftains.

An example of this local independence is seen during this reign when Iwai, the lord of Northern Kyushu, flexes his muscles and tries to take control of the shipping routes between the archipelago and the continent. This is ultimately put down by a military expedition, suggesting that Yamato did possess some amount of military coercive power, along with any spiritual or religious cachet they may have had.

It also seems quite likely that another component holding things together among these different polities were the various marriage alliances. We’ve seen this in the ancient stories and so it is quite possibly true that Wohodo did have both paternal and maternal connections to Yamato. It is also possible that these were just two in a web of relationships that could have been called on, and doesn’t necessarily mean that he had the strongest claim to the throne. In fact, the Chronicles even point out that there was another candidate who also was selected before him, but who fled due to the Yamato court’s poor communication tactics.

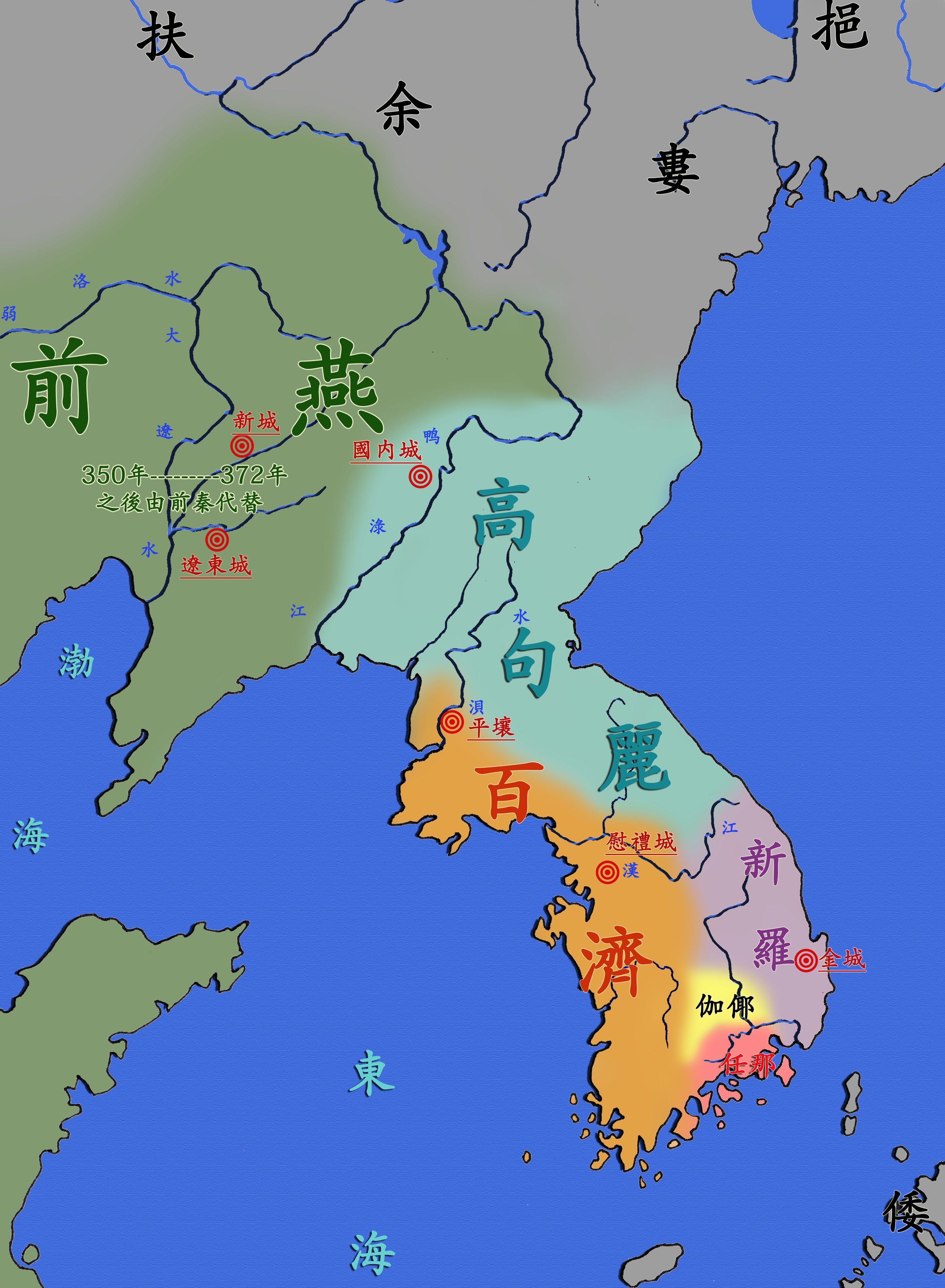

Overall, it is unclear why Wohodo was chosen as sovereign, and even his hand in things seems relatively light. In the Chronicles, the focus during this reign is much more on those serving the court. This includes individuals like Hodzumi no Omi no Oshiyama, Mononobe no Ohomuraji no Arakahi, Kena no Omi, and, of course, Ohotomo no Ohomuraji no Kanamura. Even then, most of the reign seems to be dealing with the interactions between Yamato and the continent. Tamna, Baekje, Nimna, Kara, Silla, Ara, and other polities are all brought up, some appearing in the narrative for the first time here. Even the rebellion of Iwai, in Northern Kyushu, was focused on its effects with continental relations.

The Sendai Kuji Hongi focuses just on the events in the archipelago and, even then, on the actions of the sovereign and the royal family. Most of it is genealogical, though it does note specifically that Prince Magari Ohoe—also known as Ohine in the Nihon Shoki—was moved in to the palace for the Heir to the Throne.

And this brings up the matter of succession, which we discussed somewhat before. Wohodo had two important wives or consorts. First, when he took the throne, Wohodo was already married to at least one wife, Menoko, the daughter of Owari no Muraji no Kusaka. Owari is the land focused on the modern area of western Aichi prefecture, including Nagoya. She is named in the Kuji Hongi as being raised up to the status of “Royal Consort” when Wohodo took the throne—normally the primary wife of the sovereign is raised up as the queen, but of course, our story took a turn and the court suggested that Wohodo marry a second woman, Tashiraka hime and raise her up as his queen.

This strikes me as an overtly political action. Tashiraka hime was either the daughter of Woke no Ohokimi, aka Ninken Tennou, and thus sister to the previous sovereign, Wohatsuse, or, by inference, the daughter of Shiraga no Ohokimi, aka Seinei Tennou, though this seems less likely to me. Whatever the case, she is presented as a daughter from the previous royal line, so by suggesting that Wohodo marry her, the court may have been trying to help legitimize his rule—either that, or this is a fictional connection inserted by the Chroniclers to try to sort things out later.

Because you see, when Wohodo no Ohokimi died, which happened in either 531 or 534—there is some disagreement—it wasn’t his son by his second wife and full Queen Tashiraka hime who succeeded him. Rather it was Magari no Ohine, his eldest son by his first wife and consort Menoko, who came to the throne and is known as Ankan Tennou. Skipping ahead, we’ll see that both of Menoko’s sons would take the throne, albeit briefly. Prince Ohine took the throne for about 2 years, and his brother, Take Ohiro Kunioshi Tate would reign for three, being named Senka, or Senkwa, Tennou by the Chroniclers. It was only after those five years that the son of Wohodo and his Queen, Ame Kunioshi Hirakihiro Niha, actually took the throne.

The Nihon Shoki claims that this son, aka Kimmei Tennou, was the rightful heir, but that he was too young, and so his brothers took the throne until he was old enough. This seems more than a little suspicious, however. First of all, both of the brothers are counted as full sovereigns—as Ohokimi—and part of the line of succession, as opposed to simply being counted as regents, holding the throne until their little brother came of age. It is said their father died at the age of 82, so it is quite possible they were already in their 60s by the time they took the throne themselves, depending on when they were actually born—though records claim they were in their 70s.

It is also curious that Ohine, the first to succeed his father, was clearly counted as the Crown Prince—he was set up in the palace reserved for the Crown Prince and was clearly involved in governmental affairs, as Crown Princes have been known to do before.

In fact, it seems to me that Ohine and his full brother were legitimate heirs, and that something later happened to put Ame Kunioshi on the throne—and we can talk about that later.

By the way, I mentioned there is some disagreement about the actual dates of Wohodo’s demise. The Nihon Shoki uses 531, which seems drawn from the Baekje Annals and their account, which the compilers found more trustworthy. However, it mentions that other accounts give another year, the 28th year of the reign instead of the 25th, which would have made it 534, instead. This year is the same one given in the Sendai Kuji Hongi, but it is also significant because according to all accounts, Magari no Ohine ascended the throne the same year that his father, Wohodo no Ohokimi, passed away. If this is, indeed, the 28th year then everything appears to work out just fine, but otherwise we end up with a three year gap, at least if the stem and branch system is to be believed.

Now, truth be told, Magari no Ohine’s time on the throne was not long, but there is a fair amount discussed during his reign, nonetheless. We’ve already talked about a couple of things that happened during his father Wohodo’s reign, while Ohine was a prince.

First off, you may recall from last episode that Ohine had courted and wed Princess Kasuga, herself also a daughter of Oke no Ohokimi, aka Ninken Tenou, though only a half-sister to Wohatsuse no Ohokimi and Princess Tashiraga. He did it himself, without any urging by the court, it seems, but it still seems that there is more evidence here of them intertwining the various lineages; two of Wohatsuse’s sisters have now been made queens, greatly increasing the chances that one of their progeny will rule in the future. This speaks, it seems, to the importance of the maternal line itself. The Chronicles take time to note that Wohodo’s mother was descended from Ikume Iribiko, and to be raised up as a “Queen” one had to be able to draw a connection to a royal lineage. Even if those connections are, shall we say, less than accurate, the need for at least the fiction is itself telling in terms of what was valued.

The other thing we notice is that Ohine showed up to intervene when Kanamura gave away part of Yamato’s territory to Baekje. Without getting too much into whether or not it was actually Yamato’s territory to give up, Ohine was certainly protesting any attempt to diminish the power of Yamato and clearly playing an important role in the government. We talked last episode about how he sent someone to stop the ambassadors on their way, but they said that it was “better to be beaten with a smaller stick than a larger one”. While this speaks to the authority of Wohodo no Ohokimi over the then Prince Ohine, it seems to also indicate that Prince Ohine himself held some clout as well, just not enough to overturn Ohokimi’s decision. Note that none of the other princes are mentioned at all, other than for genealogical purposes.

So, Ohine comes to the throne. Magari no Ohine is also given the name Magari no Ohoye Hiro Kunioshi Take. “Ohoye” may just reference his position as the eldest sone of Wohodo no Ohokimi.

As was typical, Ohine—or Ohoye, but for now I’ll stick with the name we first got to know him by—moved the court to a palace in Magari no Kanahashi, which is likely where he gets his name, one possible reading of which could be “the elder son of Magari”. While Kasuga no Yamada was his main squeeze and raised up as queen, he had several other consorts, including two daughters of the late Kose no Obito, who had been Oho-omi during his father’s reign, as well as a daughter of Mononobe no Itahi, who had been made Ohomuraji back in the reign of Woke no Ohokimi—that is to say, Ninken Tennou.

There are several stories from Ohine’s reign that I’m going to talk about, and they all center around the royal granaries, or Miyake. These appear to have been centralized mechanisms for storing and distributing rice, sources of income for the court and its various members that could be granted or transferred as needed. More importantly, they were attached to certain lands and the income from that land. Presumably whoever owned or controlled a given storehouse would benefit from the rice that came to it.

Since Ohine had no children—or at least no heirs—Kanamura suggested that all of the consorts be given grants of Miyake. I presume this was to ensure that they had a means of supporting themselves after he passed away. He also had various familial -Be groups created, including the Magari no Toneri-Be and the Magari no Yuki-Be, presumably to commemorate his name, Magari no Ohine.

He also is credited with creating a group called the Inukahi-be, or the Dog Keeper’s -Be. This is an interesting one, and some ancient explanations suggest it might be tied in with all of the Miyake that were being created. Even back in those days, guard dogs were apparently a thing, and so having a hereditary group of dog keepers who were responsible for ensuring that dogs were guarding the granaries seems to make as much sense as anything else. It also would explain why, in the following line, we are told that Sakuri Tanabe no Muraji, Agata no Inukahi no Muraji, and Naniwa no Kishi were put in charge of the revenues from the Miyake. “Agata no Inukahi” would seem to mean the “district dog keeper”, and if the Inukahi-Be were assisting with the operation of the Miyake, it would make sense that they would also be one of those in charge of the revenues, and likely ensuring that they were properly administered.

Another take on this, though, could be a more standardized and centralized approach to administration of the Miyake and their revenues. After all, centralization has been a continuing theme throughout the formation of the Yamato state.

One of the first granary stories from Ohine’s reign concerns Kashiwade no Omi no Ohomaro. Ohomaro sent a messenger to Ishimi in the land of Fusa, in what would later be Kazusa province, part of modern Chiba prefecture on the Boso peninsula. The messenger asked for local pearls, presumably for the court, but the lord of Ishimi—which is to say the Ishimi Kuni no Miyatsuko—delayed their shipment. Ohomaro was quite upset when he learned what had happened, and ordered that the Kuni no Miyatsuko be bound and interrogated.

Here, according to Aston’s translation, one “Wakugo no Atahe” and other Kuni no Miyatsuko who were at the court fled and hid in the Queen’s private apartments. When the Queen, Kasuga no Yamada saw them, she fell down in shame, or possibly shock. In atonement for their intrusion into the Queen’s quarters they offered her the Miyake, or royal granaries, of Ishimi as her private property.

Looking at the original characters, I have to say I’m a bit perplexed. Reading between the lines, I wonder if Wakugo no Atahe isn’t the Kuni no Miyatsuko of Ishimi that was going to be bound and interrogated for holding back the pearls, or else it could refer to his son—the Kuni no Miyatsuko no Wakugo no Atahe. That would better explain why this person would want to hide, especially given what we’ve seen about the use of ordeals during this time to prove guilt or innocence. It would also explain why he would have any authority to give up the granaries of Ishimi, along with the rice land that fed into them.

This anecdote also notes the severity of entering the Queen’s private quarters, or the Hinter Palace, unannounced.

Later, another grant of a Miyake would be established to help pay for the erection of a “Pepper Court”—a Han dynasty term for royal apartments for the Queen. The term may have originated from the idea of either smearing the walls with pepper, hoping it would help keep the occupants warm, or perhaps it was because pepper flowers were delivered, in the hopes that the Queen would be as fruitful as the plant itself.

Whatever the reason, including the question of why one was needed, as it seems the Queen had perfectly good apartments already, the court selected commissioners to go out and find good rice land to select for this project.

Now let’s be clear, they weren’t looking for land that *might* be good for growing rice so they could open new fields. No, they were looking for land that was already quite profitable. Rice was already one of the main commodities and the basis for the economy. You may as well be looking for a nice big wad of cash that you could just take.

And so you might imagine that not everyone would be exactly pleased to simply give up their own source of income and livelihood. Such was the case with Ohoshi Kawachi no Atahe no Ajihari. The commissioners suggested that Ajihari offer up his own rice land of Kiji, but Ajihari had othe ideas. He lied to the commissioners and told them that the land might look nice, but it was prone to drought and other problems. And so their report recommended against it, and apparently they kept searching.

About 6 months later, during the intercalary 12th month—that is to say an extra twelfth month added in to get the lunar calendar and the solar calendar synched up again—the sovereign himself went to Mishima, accompanied by our old friend, Ohotomo no Kanamura.

There they inquired about the rice-land of Ihibo, the Agatnushi, or district lord. In response he offered them Upper and Lower Mino, Upper and Lower Kuwabara, and Takefu—a total of 40 cho of land, where 1 cho, or “village”, of land is equal to a square, roughly 60 steps by 60 steps to a side. Later on, this would measure out as not quite 10,000 square meters, or about 1 hectare. So we can say that this was roughly 40 hectares or around 90 to 100 acres of land.

The Chronicles then record a speech by Kanamura, though I suspect it is more moralizing on the part of the Chroniclers. In the speech he notes how freely Ihibo offered up his land, and notes that it is established precedent that all land actually belongs to the sovereign. Essentially there is no such thing as private ownership—any appearance of ownership was just a grant by the Crown to use the land. Thus they could also institute imminent domain whenever they wanted and basically take whatever they deemed necessary. Of course, in practice, this was a bit more difficult, but that was the theory that allowed them to do it.

Here Ajihari is called out in contrast to Ihibo, with Kanamura accusing Ajihari that he “didst suddenly entertain a grudging as regards the lands of the Crown”. Because of this, Ajihari was stripped of his position as local governor. He prostrated himself and offered up five hundred labourers every spring and autumn. He also presented six cho worth of rice-land in Sawida to Kanamura, personally.

Meanwhile, Ihibo was overjoyed and offered up his son, Toriki, as a servant to Kanamura.

So what are we to make of all of this? For one thing, it is establishing the precedent of the throne’s ownership of the lands—something that has come up before, but this reinforces it. We also see how rewards and punishments could work within the framework of the court. I actually have to wonder if Ajihari wasn’t originally the Agatanushi, which was then stripped from him and given to Ihibo because of this loyalty. It is hard for me to say for certain, but it does appear that all of this is happening in and around what was then known as the land of Kawachi.

We also see evidence how, to get out of punishment, elites might offer up what are effectively bribes to the court and court officials. Here we see that both Ihibo and Ajihari are outright giving things to Ohotomo no Kanamura, and not just to the Crown. Once again, Kanamura’s own prominence is hard to miss, here.

Miyake being given in exchange for leniency, or as part of some judgment is a continued theme. For instance, we have another story during this reign: during the same month when everything we’ve just been talking about went down with Ajihari and Ihibo, Hata Hime, daughter of Ihoki-Be no Muraji no Kikoyu, stole a necklace belonging to Mononobe no Okoshi. Okoshi would later be made Ohomuraji a few reigns later, so he was someone of note.

This crime was discovered when Hata hime attempted to give the necklace to the Queen, Kasuga. When the deed was made public, Hata-hime’s father Kikoyu gave up his own daughter to be a servant of the Uneme—so a servant to the Queen’s servants. He also gave up the Miyake of Ihokibe over in the land of Aki, in the western part of modern Hiroshima prefecture. This was given to the sovereign.

And even though he technically had not done anything wrong, Okoshi, the owner of the necklace that got stolen, also presented the sovereign with various Be and villages, such as the Towochi Be, as well as the villages of Kusasa and Toi; and also Nihe no Hasebe, in the modern prefecture of Ise.

Then there is the story of the Omi and his relative, Wogi, who both were vying for position as the Kuni no Miyatsuko of the province of Musashi. Their dispute continued for years, until finally Wogi reached out to Wokuna, the Kuni no Miyatsuko of Kamitsukenu, aka Kozuke, and he suggested that they assaniate Omi, making Wogi the new lord. Omi heard about this and fled to the court, where he pled his case. There they decided to make Omi the rightful Kuni no Miyatsuko, and Wogi was put to death.

In thanks for the ruling, Omi offered up four Miyake—those of Yokonu, Tachibana, Ohohi, and Kurasu.

A few other things occurred during this reign. For one, we see an embassy from Baekje, bringing the standard “tribute”. We also see the sovereign installing cattle on the islands of Ohosumi Island and Hime Island, at Naniwa.

The cattle are interesting. Up to this point we haven’t seen too much on cattle. Mostly they required a fair bit of resources. They were needed as oxen for the cart, but there are some beef and even milk recipes that show up—largely medicinal purposes. The royal family themselves would maintain herds of cattle for medicinal use for several centuries before entirely dropping it. Japan wouldn’t really pick up a taste for beef and dairy again until much later.

And that covers the reign of Magari no Ohine, aka Ankan Tennou. He was buried, they say, at Takaya Hill at Furuichi in the land of Kawachi. We are told that his queen, Kasuga no Yamada, and his sister, Kamisaki, were both buried with him.

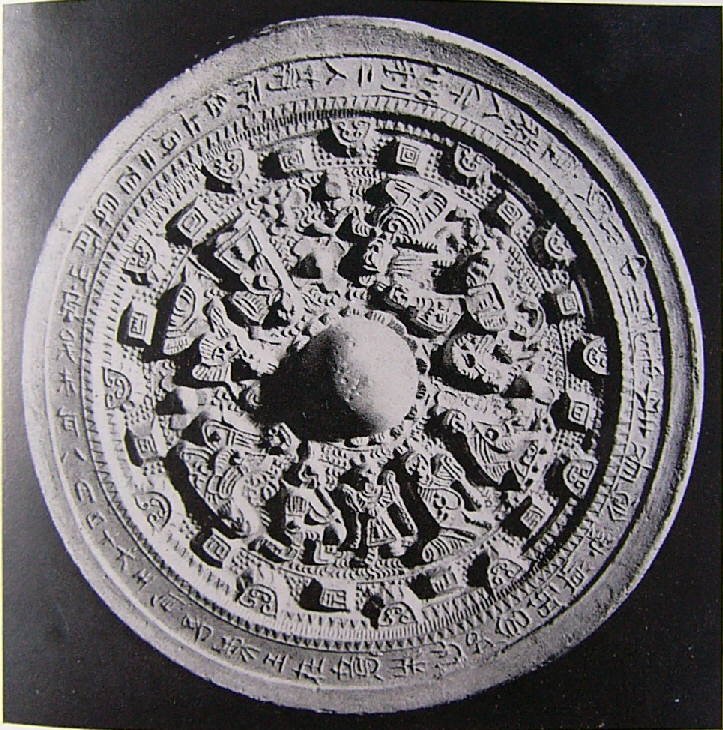

Next episode we will recap the year, as we are approaching that time. And then we’ll get into Ohine’s brother, also known as either Senka or Senkwa, depending on the romanization. Before we do that, though, I would like to talk a little bit about a piece of glass, attributed to none other than Ankan himself. So expect something on that as well.

Until then, thank you for listening and for all of your support. If you like what we are doing, tell your friends and feel free to rate us wherever you listen to podcasts. If you feel the need to do more, and want to help us keep this going, we have information about how you can donate on Patreon or through our KoFi site, ko-fi.com/sengokudaimyo, or find the links over at our main website, SengokuDaimyo.com/Podcast, where we will have some more discussion on topics from this episode.

Also, feel free to Tweet at us at @SengokuPodcast, or reach out to our Sengoku Daimyo Facebook page. You can also email us at the.sengoku.daimyo@gmail.com. It is always great to hear from people and ideas for the show.

And that’s all for now. Thank you again, and I’ll see you next episode on Sengoku Daimyo’s Chronicles of Japan.

References

Barnes, Gina L. (2015). Achaeology of East Asia: The Rise of Civilization in China, Korea and Japan

Kiley, C. J. (1973). State and Dynasty in Archaic Yamato. The Journal of Asian Studies, 33(1), 25–49. https://doi.org/10.2307/2052884

Aston, W. G. (1972). Nihongi, chronicles of Japan from the earliest times to A.D. 697. London: Allen & Unwin. ISBN0-80480984-4

Philippi, D. L. (1968). Kojiki. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press. ISBN4-13-087004-1