Previous Episodes

- June 2025

- May 2025

- April 2025

- March 2025

- February 2025

- January 2025

- December 2024

- November 2024

- October 2024

- September 2024

- August 2024

- July 2024

- June 2024

- May 2024

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

It's the last episode of 2023, and our 100th episode! But despite that, we keep on moving through the period, hitting a bunch of smaller stories from the Nihon Shoki about this period.

We talk about Zentoku no Omi, the temple commissioner of Hokoji, as well as the trouble they went through to get the Asukadera Daibutsu in place to begin with. We have the first instance of the Dazai--as in the Dazaifu of Kyushu--as well as the first instance of the holiday that would eventually become Children's Day, Kodomo no Hi. There are various immigrants, bringing painting, handmills, and even a new kind of musical dance theater known as gigaku. And that's just some of what we'll cover.

By the way, quick note about Buddhist temples in Japan. The temple names typically end with the suffix “-ji” (寺), so Hōkōji is literally “Hōkō Temple”. However, there are also other suffixes, such as “-in” (院) like the Byōdōin. Often these may be part of a larger temple, but can be viewed as a temple themselves. We are therefore left with the dilemma of whether to just say “Hōkōji” or “Byōdōin” or to say “Hōkōji Temple” and “Byōdōin Temple” in order to be clear. For me, I tend to choose the former, so as not to repeat myself (“Hōkōji Temple” is basically saying “Hōkō Temple Temple”), but on occasion I will use it for clarity.

Zentoku no Omi

Zentoku no Omi (善徳臣) is said to be the son of the “Oho-omi” (大臣), aka Soga no Umako. Since his other son, Soga no Emishi, would probably have been about 11 years old at this point in time, it is thought that Zentoku was older to be given the post of Temple commissioner, or tera-no-tsukasa (寺造), which seems a logical conclusion. Interestingly, it would be Emishi who would go on to head up the family in later years.

Temporary Palace of Miminashi and the Move to Oharida

Kashikiya Hime’s first palace was at Toyora (Toyoura), but here we are told that she was in a temporary palace as heavy rains had flooded the “palace”—which may be referring to Toyora. Shortly thereafter they moved to the Oharida (or Woharida) palace, traditionally placed just to the north, but some archaeologists have suggested that it may be just across the Asuka river on the other side, instead. This was all very close to Hōkōji and the Soga family mansion. Toyora was then given over completely to be the nunnery companion to Hōkōji.

Introduction of the Hirami

The hirami is a pleated, wrapped skirt, and for more, check out our entry in the section of Men’s Garments here on the website.

Installation of the Buddha Image at Hōkōji

When the giant Buddha at Hōkōji was installed it seems that there was a bit of a problem, as it wouldn’t fit through the doorways of the kondō, or Golden Image Hall. Fortunately, the person who designed the image, Kuratsukuri no Tori, had an idea.

Baekje Priests Land at Ashigita

The story about a boatload of Baekje priests who were bound for Wu being turned back and blown off course seems reasonable enough, but it is interesting that they stop at Ashigita, in Tsukushi. Ashigita has previous connections to Baekje, going back at least to the stories about Nichira, aka Illa.

First Mention of Dazai

The position of Dazai (太宰) was extremely important in helping to extend the power of the court in the Yamato region all the way out to the far western edge of the archipelago. We’ve seen it grow from a military post into something much more. This would also become the primary receiving point for most guests to Yamato from the 7th century onward, at modern Fukuoka. It probably is one of the best indicators for the extension of Yamato control all the way out to the westernmost edge, but it was also a heck of a long way from the center of politics at court.

Tango no Sekku

The early festival of 5/5 was based around gathering herbs or flowers, possibly for medicinal purposes and to “ward off evil”, which amount to the same thing. Around the Kamakura period it would morph into the “Boy’s Day” festival and later become a generic “Kodomo no Hi”, or “Children’s Day”

Re-interment of Kitashi Hime

It was not uncommon for someone to be placed in a temporary burial and then later have the bones buried in the final resting place. This was especially the case if the final tomb mound wasn’t ready, yet. By this point, many tombs were made so that they could be reopened, and we have evidence that there were people buried at different times in the same chamber, even. Still, one has to also wonder if this wasn’t making a statement about the legitimacy of the Soga lineage, now that several of her children had sat on the throne. She was being treated with the full honors of having been Queen.

Shikomaro

It is interesting that we get a look at a potential ancient disease, here: ringworm. Not surprising that people might want to throw him overboard, as disease was something very much to be afraid of at this time, since causes and cures were both largely unknown. What medicines were available may or may not have been effective at anything beyond treating the symptoms. Assuming it was ringworm then they probably were correct that it was infectious—it can be transferred through skin to skin contact, and a boat is not a large place to begin with. So I guess it was a good thing he had some skills that made people think they should tolerate him. That said, ringworm is still common, today, and while it may be annoying it is generally not something that is known as a major mortality factor.

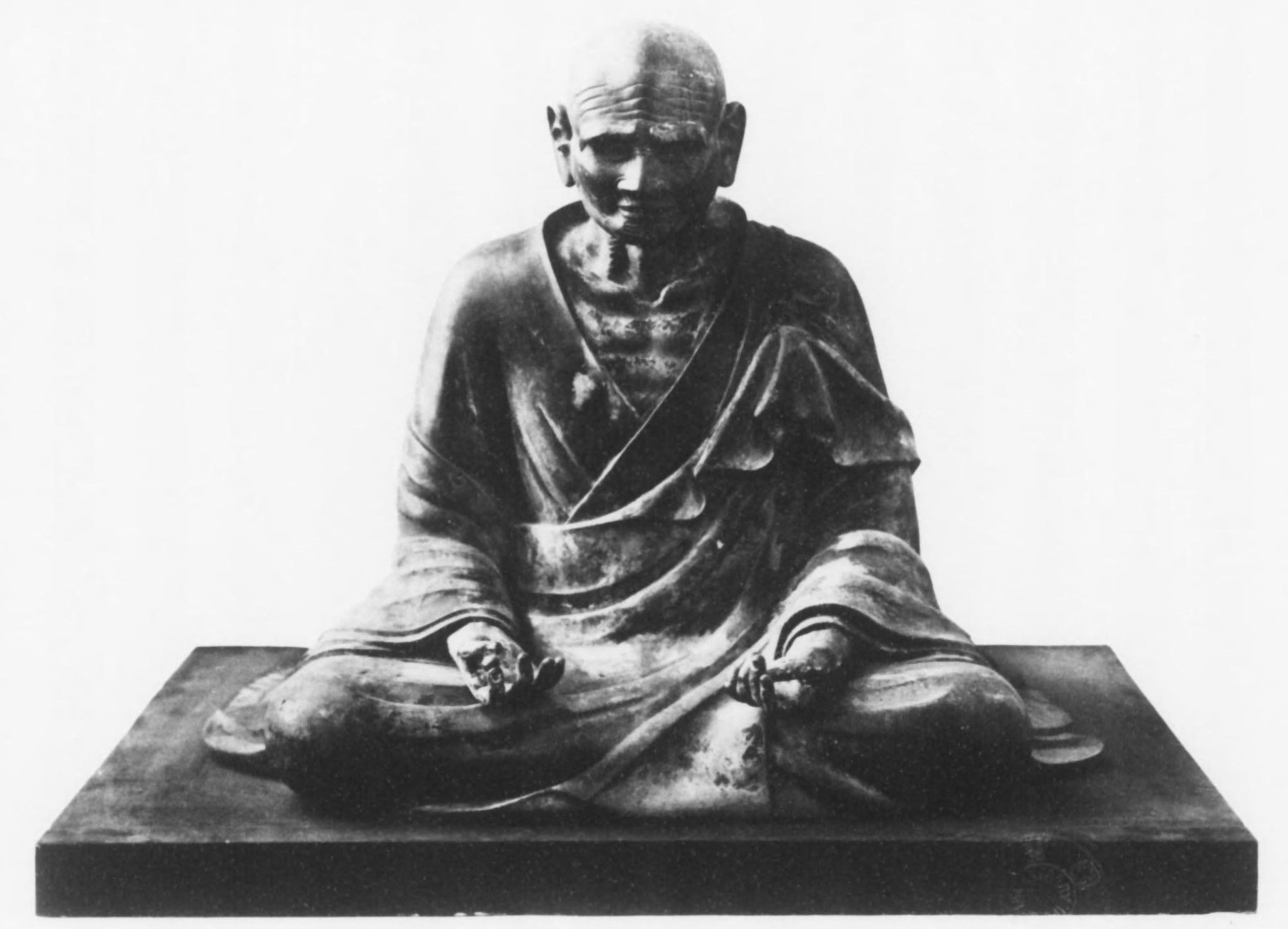

Gigaku

Finally, we have Mimashi introducing Gigaku (伎楽). This is different from Gagaku (雅楽), and you can see one of the classic Gigaku masks at the top of this page.

-

Welcome to Sengoku Daimyo’s Chronicles of Japan. My name is Joshua, and this is episode 100: Sacred Tetris and Other Tidbits

First off: woohoo! One hundred episodes! Thank you to everyone who has been listening and following along on this journey so far. When I started this I had no idea how long I would be able to keep up with it, but I appreciate everyone who has encouraged me along the way. This all started in September of 2019, and we are now four years in and we have a ways to go. While I’m thanking people, I’d also like to give a big thank you to my wife, Ellen, who has been helping me behind the scenes. She’s the one who typically helps read through what I’m going to say and helps edit out a lot of things, and provides reminders of things that I sometimes forget. She really helps to keep me on track, and I always appreciate the time she puts into helping to edit the scripts and the questions she asks.

Now, we are still talking about the 6th and early 7th centuries during the reign of Kashikiya Hime, aka Suiko Tenno. We’ve talked about a lot of different aspects of this period—about the conflicts over Nimna on the peninsula, about the rise of the Sui dynasty on the continent, and the importation of various continental goods, including animals, immigrants, and knowledge. That knowledge included new ideas about governance as well as religious practices such as Buddhism—and possibly other religious practices as well, as many of the stories that we saw in the Age of the Gods may have analogs on the continent and may just as easily have been coming over with the current crop of immigrants, though it is hard to say for certain. At the heart of these changes are three individuals. Obviously there is Kashikiya Hime, on the throne through a rather intricate and bloody series of events. Then there is Soga no Umako, her maternal uncle, who has been helping to keep the Soga family on top. And of course, the subject of our last couple episodes, Prince Umayado, aka Shotoku Taishi. He, of course, is credited with the very founding of the Japanese state through the 17 article constitution and the promulgation of Buddhism.

This episode, I’d like to tackle some of the little things. Some of the stories that maybe didn’t make it into other episodes up to this point. For this, we’ll mostly look at it in a chronological fashion, more or less.

As you may recall, Kashikiya Hime came to the throne in about 593, ruling in the palace of Toyoura. This was around the time that the pagoda was erected at Houkouji temple—and about the time that we are told that Shitennouji temple was erected as well. Kashikiya Home made Umayado the Crown Prince, despite having a son of her own, as we’d mentioned previously, and then, in 594, she told Umayado and Umako to start to promulgate Buddhism, kicking off a temple building craze that would sweep the nation—or at least the areas ruled by the elites of Yamato.

By 596, Houkouji was finished and, in a detail I don’t think we touched on when talking about Asukadera back in episode 97, they appointed as commissioner one Zentoku no Omi—or possibly Zentoko, in one reading I found. This is a curious name, since “Zentoku” comes across as a decidedly Buddhist name, and they really liked to use the character “Zen”, it feels like, at this time. In fact, it is the same name that the nun, the daughter of Ohotomo no Sadehiko no Muraji, took, though the narrative is very clear about gender in both instances, despite them having the exact same Buddhist names. This name isn’t exactly unique, however, and it is also the name recorded for the Silla ruler, Queen Seondeok, whose name uses the same two characters, so it is possible that at this time it was a popular name—or perhaps people just weren’t in the mood to get too creative, yet.

However, what is particularly interesting to me, is that the name “Zentoku” is then followed by the kabane of “Omi”. As you may recall from Episode XX, a kabane is a level of rank, but associated with an entire family or lineage group rather than an individual. So while there are times where we have seen “personal name” + “kabane” in the past, there is usually a surname somewhere in there. In this case, we aren’t told the surname, but we know it because we are given the name of Zentoku’s father: we are told that he was the son of none other than the “Oho-omi”, the Great Omi, aka Soga no Umako. So, in summary, one of Soga no Umako’s sons took the tonsure and became a monk.

I bring this little tidbit up because there is something that seems very odd to me and, at the same time, very aristocratic, about taking vows, retiring from the world, and yet still being known by your family’s title of rank. Often monks are depicted as outside of the civil rank and status system—though there were certainly ranks and titles within the priesthood. I wonder if it read as strange to the 8th century readers, looking back on this period. It certainly seems to illustrate quite clearly how Buddhism at this point was a tool of the elite families, and not a grass-roots movements among the common people.

This also further strengthens the idea that Houkouji was the temple of the Soga—and specifically Soga no Umako. Sure, as a Soga descendant, Prince Umayado may have had some hand in it, but in the end it was the head of the Soga family who was running the show, and so he appoints one of his own sons as the chief commissioner of the temple. They aren’t even trying to hide the connection. In fact, having one of his sons “retire” and start making merit through Buddhist practice was probably a great PR move, overall.

We don’t hear much more from Zentoku after this point, and we really know very little about him. We do know something about the Soga family, and we know that Soga no Umako has at least one other son. While we’ve yet to see him in the narrative—children in the Nihon Shoki are often meant to be neither seen nor heard, it would seem—Umako’s other son is known to us as Soga no Emishi. Based on when we believe Soga no Emishi was born, however, he would have been a child, still, when all this was happening, and so Zentoku may have actually been his father’s eldest son, taking the reins at Houkouji temple, likely setting him up to claim a role of spiritual leadership in the new religion of Buddhism. Compare this to what we see later, and also in other places, such as Europe, where it is often the second son that is sent into religious life, while the eldest son—the heir—is kept at hand to succeed the father in case anything happens. On the other hand, I am unsure if the monks of this time had any sort of celibacy that was expected of them, and I suspect that even as the temple commissioner, the tera no Tsukasa, Zentoku was keeping his hand in. After all, the Soga family head appears to have been staying near the temple as well, so it isn’t like they were packing him off to the high mountains.

Moving on, in 601 we are told that Kashikiya Hime was in a temporary palace at a place called Miminashi, when heavy rains came and flooded the palace site. This seems to be referring to flooding of Toyoura palace, which was, we believe, next to the Asuka river. I wonder, then, if that wasn’t the impetus for, two years later, in 603, moving the palace to Woharida, and leaving the old palace buildings to become a nunnery. That Woharida palace is not thought to have been very far away—traditionally just a little ways north or possibly across the river.

In 604, with the court operating out of the new Woharida palace, we see the institution of more continental style traditions. It includes the idea of bowing when you entered or left the palace grounds—going so far as to get on your hands and knees for the bow. Even today, it is customary to bow when entering a room—particularly a traditional room like in a dojo or similar—and it is also customary to bow when passing through a torii gate, entering into a sacred space. Of course, that is often just a standing bow from the waist, and not a full bow from a seated position.

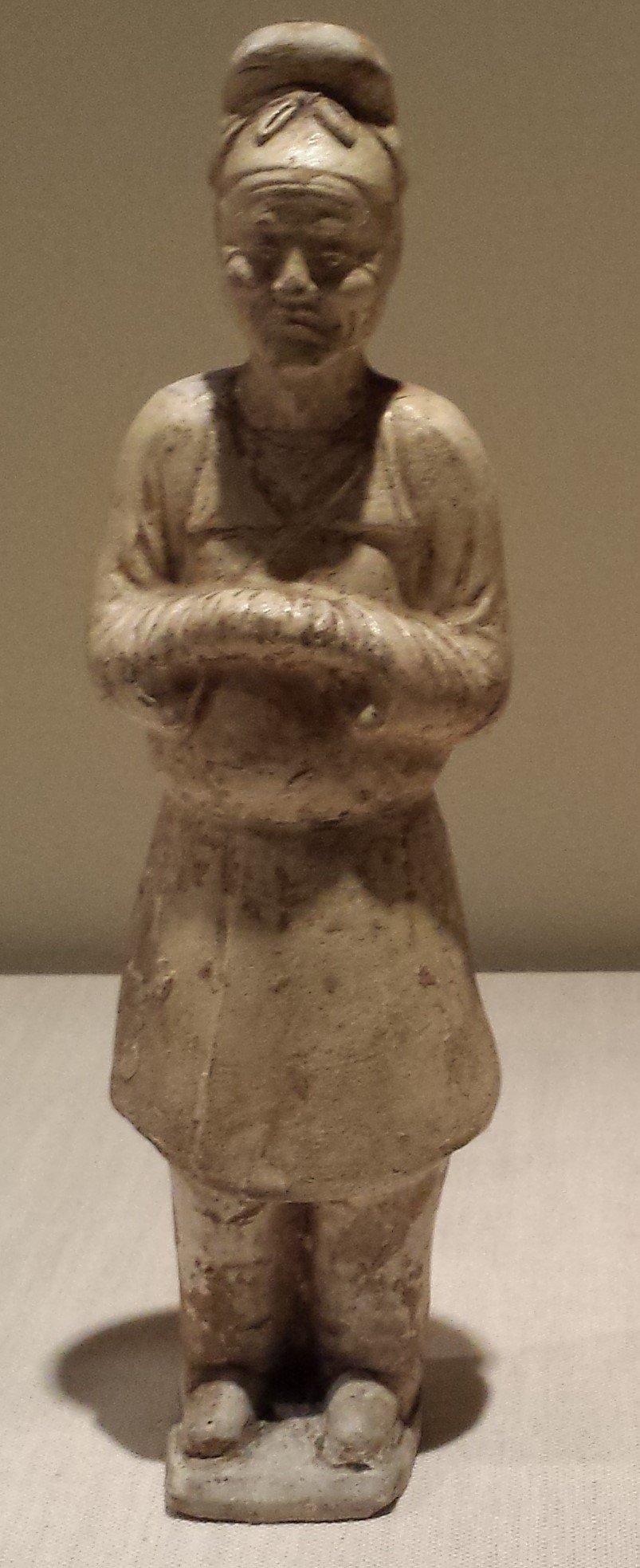

In 605, with more continental culture being imported, we see it affecting fashion. In fact, in this year we are told that Prince Umayado commanded all the ministers to wear the “hirami”. The kanji simply translates to “pleats”, but in clothing terms this refers to a pleated skirt or apron. We see examples of this in courtly clothing going back to at least the Han dynasty, if not earlier, typically tied high above the waist and falling all the way down so that only the tips of the shoes are poking out from underneath. We have a bit more on this in the historical clothing section of the Sengoku Daimyo website, sengokudaimyo.com.

I wonder if these wrapped skirts aren’t some of what we see in the embroidered Tenjukoku mandala of Chuuguuji. Court women would continue to wear some kind of pleated skirt-like garment, which would become the mo, though for men they would largely abandon the fashion, except for some very specific ritual outfits. That said, there is still an outfit used for some imperial ceremonies. It is red, with many continental and what some might consider Taoist symbols, such as dragons, the sun and moon, etc.. That continuation of tradition gives us some idea of what this was and what it may have looked like back in the day. It is also very neat that we are starting to get specific pieces of potentially identifiable clothing information, even if it is only for the court nobles.

The year following that, 606, we get the giant Buddha image being installed at Houkouji, aka Asukadera. Or at least, we think that is the one they are talking about, as we can’t be one hundred percent certain. However, it is traditionally thought to be one and the same. The copper and gold image was commissioned a year prior, along with an embroidered image as well, but when they went to install it they ran into a slight problem: The statue was too large to fit through the doors of the kondo, the golden image hall. No doubt that caused some embarrassment—it is like ordering furniture that won’t fit through the doorway, no matter how you and your friends try to maneuver it around. They were thinking they would have to cut through the doors of the kondo to create more room, and then fix it afterwards. Nobody really wanted to do that thought—whether because they thought it would damage the structural integrity of the building or they just didn’t want to have to put up with an unsightly scar, it isn’t clear. Finally, before they took such extreme measures, they called on the original artist, Kuratsukuri no Tori. He is said to be the son of the famous Shiba Tattou, and so his family was quite close with the Soga, and he seems to have had quite the eye for geometry as we are told that he, “by way of skill”, was able to get it through the doors and into the hall. I don’t know if that meant he had to some how turn it on its side and walk it through, or something else, but whatever it was, it worked. Tori’s mad Tetris skills worked, and they were able to install the giant Buddha in the hall without cutting through the doorways.

For his efforts, Tori was rewarded, and he was raised up to the rank of Dainin, one of the 12 new ranks of the court. He was also given 20 cho worth of “water fields”—likely meaning rice paddies. With the income from those fields, we are told that he invested in a temple of his own: Kongoji, later known as the nunnery of Sakata in Minabuchi.

For all that Buddhism was on the rise, the worship of the kami was still going strong as well. In 607 we are told that there was an edict that everyone should worship the kami of heaven and earth, and we are told that all of the noble families complied. I would note that Aston wonders about this entry, as the phrasing looks like something you could have taken right out of continental records, but at the same time, it likely reflects reality to some extent. It is hard to see the court just completely giving up on the traditional kami worship, which would continue to be an important part of court ritual. In fact, it is still unclear just how the new religion of Buddhism was viewed, and how much people understood the Buddha to be anything more than just another type of kami.

Later in that same year was the mission to the Sui court, which we discussed in Episode 96. The year after, the mission returned to Yamato with Sui ambassadors, and then, in 609, those ambassadors returned to the Sui court. These were the missions of that infamous letter, where the Yamato court addressed the Sui Emperor as an equal. “From the child of heaven in the land where the sun rises to the child of heaven in the land where the sun sets.” It is still one of my favorite little pieces of history, and I constantly wonder if Yamato didn’t understand the difference in scale or if they just didn’t care. Either way, some really powerful vibes coming off that whole thing.

That same year that the Sui ambassadors were going back to their court there was another engagement with foreigners. In this case the official on the island of Tsukushi, aka Kyuushuu, reported to the Yamato court that 2 priests from Baekje, along with 10 other priests and 75 laypersons had anchored in the harbor of Ashigita, in the land of Higo, which is to say the land of Hi that was farther from Yamato, on the western side of Kyuushuu. Ashigita, you may recall, came up in Episode 89 in reference to the Baekje monk—and I use that term loosely—Nichira, aka Illa. There, Nichira was said to descend from the lord of Ashigita, who was said to be Arisateung, a name which appears to be a Korean—possibly Baekje—title. So now we have a Baekje ship harboring in a land that once was ruled by a family identified, at least in their names or titles, as having come from or at least having ties with Baekje. This isn’t entirely surprising, as it wouldn’t have taken all that much effort for people to cross from one side to the other, and particularly during the period before there was a truly strong central government it is easy to see that there may have been lands in the archipelago that had ties to Baekje, just as we believe there were some lands on the peninsula that had ties to Yamato.

One more note before get to the heart of the matter is the title of the person who reported all these Baekje goings-on. Aston translates the title as the Viceroy of Tsukushi, and the kanji read “Dazai”, as in the “Dazaifu”, or government of the “Dazai”. There is kana that translates the title as Oho-mikoto-Mochi—the Great August Thing Holder, per Aston, who takes this as a translation, rather than a strict transliteration. This is the first time that this term, “Dazai” has popped up in the history, and it will appear more and more in the future. We know that, at least later, the Dazaifu was the Yamato court’s representative government in Kyuushuu. The position wasn’t new - it goes back to the various military governors sent there in previous reigns - but this is the first time that specific phrasing is used—and unfortunately we don’t even know much about who it was referring to. The position, however, would become an important part of the Yamato governing apparatus, as it provided an extension of the court’s power over Kyuushuu, which could otherwise have easily fallen under the sway of others, much as Iwai tried to do when he tried to ally with Silla and take Tsukushi by force. Given the importance of Kyuushuu as the entrypoint to the archipelago, it was in the Court’s best interest to keep it under their control.

Getting back to the ship with the Baekje priests on it: the passengers claimed they were on their way to Wu, or Kure—presumably headed to the Yangzi river region. Given the number of Buddhist monasteries in the hills around the Yangzi river, it is quite believable, though of course by this time the Wu dynasty was long gone. What they had not prepared for was the new Sui dynasty, as they said there was a civil war of some kind going on, and so they couldn’t land and were subsequently blown off course in a storm, eventually limping along to Ashigita harbor, where they presumably undertook rest and a chance to repair their vessels. It is unclear to me exactly what civil war they were referring to, and it may have just been a local conflict. There would be rebellions south of the Yangzi river a few years later, but no indication that it was this, just a bit out of context. We know that the Sui dynasty suffered—it wouldn’t last another decade before being dismantled and replaced by the Tang dynasty in about 618. There were also ongoing conflicts with Goguryeo and even the area of modern Vietnam, which were draining the Sui’s resources and could be related to all of these issues. If so, though, it is hard to see an exact correlation to the “civil war” mentioned in the text.

Given all this, two court nobles: Naniwa no Kishi no Tokomaro and Fumibito no Tatsu were sent to Kyuushuu to see what had happened, and, once they learned the truth, help send the visitors on their way. However, ten of the priests asked to stay in Yamato, and they were sent to be housed at the Soga family temple of Houkouji. As you may recall, 10 monks was the necessary number to hold a proper ordination ceremony, funnily enough.

In 610, another couple of monks showed up—this time from Goguryeo. They were actually sent, we are told, as “tribute”. We are told that one of them was well read—specifically that he knew the Five Classics—but also that he understood how to prepare various paints and pigments. A lot of paint and pigments were based on available materials as well as what was known at the time, and so it is understandable, to me, why you might have that as a noted and remarkable skill. We are also told that he made mills—likely a type of handmill. These can be easily used for helping to crush and blend medicines, but I suspect it could just as easily be used to crush the various ingredients for different pigments. A type of handmill, where you roll a wheel in a narrow channel, forward and back, is still in use today throughout Asia.

In 611, on the 5th day of the 5th month, the court went out to gather herbs. They assembled at the pond of Fujiwara—the pond of the wisteria field—and set out at sunrise. We are told that their clothing matched their official cap colors, which was based on their rank, so that would seem to indicate that they were dressed in their court outfits. In this case, though, they also had hair ornaments mad of gold, leopard’s tails, or birds. That leopard’s tail, assuming the description is accurate, is particularly interesting, as it would have had to have come from the continent.

This ritual gathering of herbs would be repeated on the 5th day of the 5th month of both 612 and 614. If that date seems familiar, you might be thinking of the modern holiday of Tango no Sekku, aka Kodomo no Hi. That is to say: Boy’s Day or the more gender neutral “Children’s Day”. It is part of a series of celebrations in Japan known today as “Golden Week”, when there are so many holidays crammed together that people get roughly a week off of work, meaning that a lot of travel tends to happen in that period. While the idea of “Boy’s Day” probably doesn’t come about until the Kamakura period, Tango no Sekku has long been one of the five seasonal festivals of the court, the Gosekku. These included New Year’s day; the third day of the third month, later to become the Doll Festival, or Girl’s Day; the seventh day of the seventh month, during Tanabata; and the 9th day of the 9th month. As you can see, that is 1/1, 3/3, 5/5, 7/7, and 9/9. Interestingly, they skipped over 11/11, possibly because that was in the winter time, based on the old calendar, and people were just trying to stay warm.

Early traditions of Tango no Sekku include women gathering irises to protect the home. That could connect to the practice, here, of “picking herbs” by the court, and indeed, many people connect the origins of Tango no Sekku back to this reign specifically because of these references, though there is very little said about what they were doing, other than picking herbs in their fancy outfits.

We are given a few more glimpses into the lives of the court in a few other entries. In 612, for instance, we have a banquet thrown for the high functionaries. This may have been a semi-regular occasion, but this particular incident was memorable for a couple of poems that were bandied back and forth between Soga no Umako and Kashikiya Hime. He toasted her, and she responded with a toast to the sons of Soga.

Later that year, they held a more somber event, as Kitashi Hime was re-interred. She was the sister to Soga no Umako, consort of Nunakura Futodamashiki no Ohokimi, aka Kimmei Tenno, and mother to both Tachibana no Toyohi, aka Youmei Tennou, and Kashikiya Hime, Suiko Tennou. She was re-buried with her husband at his tomb in Hinokuma. During this period, various nobles made speeches. Kicking the event off was Abe no Uchi no Omi no Tori, who made offerings to her spirit, including around 15,000 utensils and garments. Then the royal princes spoke, each according to rank, but we aren’t given just what they said. After that, Nakatomi no Miyatokoro no Muraji no Womaro gave the eulogy of the Oho-omi, presumably speaking on Umako’s behalf, though it isn’t exactly clear why, though Umako was certainly getting on in years. Then, Sakahibe no Omi no Marise delivered the written eulogies of the other families.

And here we get an interesting glimpse into court life as we see a report that both Nakatomi no Womaro and Sakahibe no Marise apparently delivered their speeches with great aplomb, and the people listening were quite appreciative. However, they did not look quite so fondly on the speechifying of Abe no Tori, and they said that he was less than skillful. And consider that—if you find public speaking to be something you dread, imagine if your entire reputation hung on ensuring that every word was executed properly. A single misstep or a bad day and suddenly you are recorded in the national history as having been just the worst. In fact, his political career seems to have tanked, as we don’t hear much more about him after that.

612 also saw more immigrants bringing more art and culture. The first was a man from Baekje. He did not look well—he had white circles under his eyes, we are told, possibly indicating ringworm or some other infection. It was so bad that the people on the ship with him were thinking about putting him off on an island to fend for himself. He protested that his looks were not contagious, and no different that the white patches of color you might see on horses or cattle. Moreover, he had a talent for painting figures and mountains. He drew figures of the legendary Mt. Sumeru, and of the Bridge of Wu, during the period of the Southern Courts, and the people were so taken by it that they forestalled tossing him overboard. He was eventually known as Michiko no Takumi, though more colloquially he was known as Shikomaro, which basically was a nickname calling him ugly, because judging people based on appearance was still totally a thing.

The other notable immigrant that year was also a man of Baekje, known to us as Mimachi, or perhaps Mimashi or Mimaji. He claimed to know the music and dancing of the Wu court—or at least some continental dynasty. He settled in Sakurawi and took on students who were basically forced to learn from him. As if a piano teacher appeared and all the children went to learn, but now it isn’t just your parents and their high expectations, but the very state telling you to do it. So… no pressure, I’m sure. Eventually, Manu no Obito no Deshi—whose name literally means “student” or “disciple”—and Imaki no Ayabito no Seibun learned the teachings and passed them down to others. This would appear to be the masked dances known as Gigaku.

If you know about early Japanese music and dance you may have heard of Gagaku, Bugaku, and Noh theater. Gagaku is the courtly music, with roots in apparently indigenous Japanese music as well as various continental sources, from the Korean peninsula all the way down to Southeast Asia. Indeed, the musical records we have in Japan are often the only remaining records of what some of the continental music of this time might have sounded like, even though the playing style and flourishes have changed over the centuries, and many scholars have used the repertoire of the Japanese court to help work backwards to try and recreate some of the continental music. The dances that you often see with Gagaku musical accompaniment are known as Bugaku, and most of that was codified in the latter years of the Heian era—about the 12th century. Then there is the famous masked theater known as Noh, which has its origins in a variety of traditions, going back to at least the 8th century and really brought together around the 14th century. All of these traditions, however, are preceded by Gigaku, this form of masked dance that came over in the 7th century, and claims its roots in the area of “Wu” rather than “Tang”, implying that it goes back to traditions of the southern courts of the Yangzi river region.

Gigaku spread along with the rest of continental culture, along with the spread of Buddhism and other such ideas. From what we can tell, it was a dominant form of music and dance for the court, and many of the masks that were used are preserved in temple storehouses such as the famous Shosoin at the Todaiji in Nara. However, as the centuries rolled by, Gigaku was eventually replaced at court by Bugaku style dances, though it continued to be practiced up through at least the 14th century. Unfortunately, I know of no Gigaku dances that survived into the modern day, and we are left with the elaborate masks, some illustrations of dancers, and a few descriptions of what it was like, but that seems to be it.

From what we can tell, Gigaku—also known as Kure-gaku, or Kure-no-utamai, meaning Music or Music and Dances of Wu—is first noted back in the reign of Nunakura Futodamashiki, aka Kimmei Tennou, but it wasn’t until the reign of Kashikiya Hime that we actually see someone coming over and clearly imparting knowledge of the dances and music—Mimashi, mentioned above. We then see the dances mentioned at various temples, including Houryuuji, Toudaiji, and others. Of course, as with many such things, Shotoku Taishi is given credit for spreading Gigaku through the Buddhist temples, and the two do seem to have gone hand in hand.

We know a little bit about the dances from the masks and various writings. The masks are not random, and a collection of Gigaku masks will have generally the same set of characters. These characters appear to have been organized in a traditional order. A performance would start with a parade and a sutra reading—which I wonder if that was original or if it was added as they grew more connected to the Buddhist temple establishment. And then there was a lion dance, where a young cub would pacify an adult lion. Lion dances, in various forms, continue to be found throughout East Asia.

Then the characters come into play and there are various stories about, for example, the Duke of Wu, and people from the “Hu” Western Regions—that is to say the non-Han people in the Western part of what is now China and central Eurasia. Some of these performances appear to be serious, while others may have been humorous interludes, like when a demon assaults the character Rikishi using a man’s genitals while calling for the “Woman of Wu”. That brings to mind the later tradition of ai-kyougen; similarly humorous or lighthearted episodes acted out during Noh plays to help break up the dramatic tension.

Many of aspects of Gigaku would go on to influence the later styles of court music and dance. Bugaku is thought to have some of its origins in masked Gigaku dancers performing to the various styles of what became known as Gagaku music. There are also examples of some of the characters making their way into other theatrical traditions, such as Sarugaku and, eventually, Noh and even folk theater. These hints have been used to help artists reconstruct what Gigagku might have been like.

One of the key aspects of Gigaku is that for all they were telling stories, other than things like the recitation of the sutras, the action of the story appears to have been told strictly through pantomime in the dances. This was accompanied by the musicians, who played a variety of instruments during the performance that would provide the musical queues for the dancers-slash-actors. There was no dialogue, however, but the names of the various characters appear to have been well known, and based on the specifics of the masks one could tell who was who and what was going on. This is similar to how, in the west, there were often stock characters in things like the English Mummers plays or the Comedia dell’arte of the Italian city-states, though in Gigaku those characters would not speak at all, and their story would be conveyed simply through pantomime, music, and masks.

There have been attempts to reconstruct Gigaku. Notably there was an attempt in the 1980s, in coordination with a celebration of the anniversary of Todaiji, in Nara, and it appears that Tenri University may continue that tradition. There was also another revival by famed Kyougen actor Nomura Mannojo, uncle to another famous Kyougen actor turned movie star, Nomura Mansai. Mannojo called his style “Shingigaku”, which seems to be translated as either “True Gigaku” or “New Gigagku”, and he took that on tour to various countries. You can find an example of his performance from the Silk Road Theater at the Smithsonian Folklife Festival in Washington, DC back in 2002, as well as elsewhere. It does appear that he’s changed things up just a little bit, however, based on his layout of the dances, but it is an interesting interpretation, nonetheless.

We may never truly know what Gigaku looked and sounded like, but it certainly had an impact on theatrical and musical traditions of Japan, and for that alone it perhaps deserves to be mentioned.

And I think we’ll stop right there, for now. There is more to get through, so we’ll certainly have a part two as we continue to look at events of this rein. There are stories of gods and omens. There is contact with an island off the southern coast of Kyuushuu. There are more trips to the Sui court. Much of that is coming. Until then, I’d like to thank you once again. I can hardly believe we reached one hundred episodes! And it comes just as we are about to close out the year.

As usual, I’ll plan for a recap episode over New Year’s, and then I’ll plan to get back into everything the episode after that, but this closes out the year. I hope everyone has a wonderful new year, however you celebrate and, as always, thank you for listening and for all of your support.

If you like what we are doing, tell your friends and feel free to rate us wherever you listen to podcasts. If you feel the need to do more, and want to help us keep this going, we have information about how you can donate on Patreon or through our KoFi site, ko-fi.com/sengokudaimyo, or find the links over at our main website, SengokuDaimyo.com/Podcast, where we will have some more discussion on topics from this episode.

Also, feel free to Tweet at us at @SengokuPodcast, or reach out to our Sengoku Daimyo Facebook page. You can also email us at the.sengoku.daimyo@gmail.com.

And that’s all for now. Thank you again, and I’ll see you next episode on Sengoku Daimyo’s Chronicles of Japan.

References

Deal, William E. and Ruppert, Brian. (2015). A Cultural History of Japanese Buddhism. Japanese Journal of Religious Studies. ISBN: 978-1-405-16700-0.

Aston, W. G. (1972). Nihongi, chronicles of Japan from the earliest times to A.D. 697. London: Allen & Unwin. ISBN0-80480984-4