Previous Episodes

- February 2026

- January 2026

- December 2025

- November 2025

- October 2025

- September 2025

- August 2025

- July 2025

- June 2025

- May 2025

- April 2025

- March 2025

- February 2025

- January 2025

- December 2024

- November 2024

- October 2024

- September 2024

- August 2024

- July 2024

- June 2024

- May 2024

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

This episode we’ll take you on a tour of the Lands of the Queen of Wa. This is the first time that we see various states of the Wa that are described as being unified under a single authority. There are only about 30 states, or countries, that are named and of those, only a handful are actually described. That said, it still gives us a jumping off point.

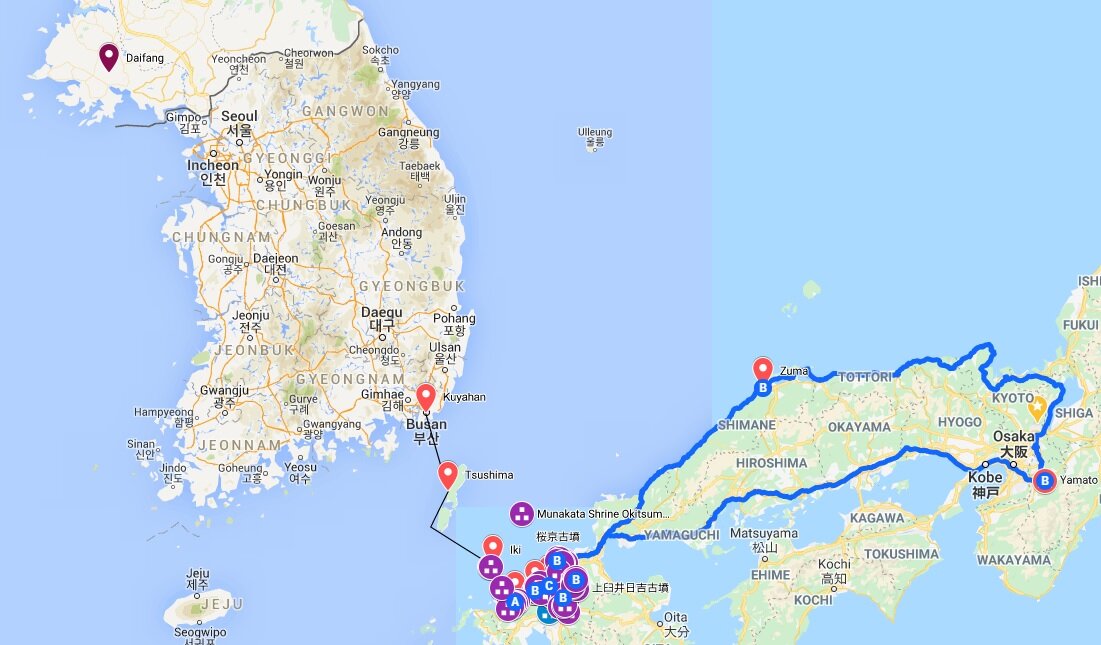

So if you are going to listen to the episode, you may want the following map. We’ve gone ahead and set up a potential map of the path from Daifang down to Yamato. It isn’t perfect, but gives you an approximation. There are also a lot of questions and assumptions. From Kuyahan (or Koya-kar(a)) on the Korean Peninsula down to Na seems pretty straightforward. The next land is “Fumi” or “Homi”, and it is not quite as clear as to where it is—but we’ll talk about that here. Zuma, or Toma, is also not quite as clear. Finally, there is Yamato—or maybe Yamatai. That’s also a bit of a quandry. Regardless, here’s our attempt at it:

Directions in the Weizhi

So first, we should talk about the directions in the Weizhi. Turns out that the directions are off. The distances might be off, but they seem like they could be relatively correct. The actual directions, though, aren’t quite right. Most of them take you south, and occasionally east. Based on those directions, Japan would appear to be upside down, stretching from the Korean straits down to at least Taiwan and maybe beyond. Perhaps that is why the chroniclers seem to have compared them to the people of Hainan south of China.

Fumi… or Homi

So this is a great example of the trouble with names at this time. First of all, everything is written in Chinese characters, not in Japanese kana, so we don’t have a clear idea of what the sounds were supposed to be. We have reconstructed some of the Ancient Chinese pronunciations, but how close those were to the Japanese, or Wa, pronunciations is hard to say. Then there are the changes in Japonic. For instance, the “F” or “H” sound was actually “P”. So “Himiko” would have been “Pimiko” and “Fumi” would have been “Pumi”. Of course, “は ひ ふ へ ほ” is “Ha Hi Fu He Ho”, so if we aren’t sure if the vowel is “u” or “o” (or if it is something in between) we get either “Fu” or “Ho”. All of this can make it quite difficult for those who aren’t Japanese linguists to make sense of the various names.

For Fumi, it is hard to see a modern equivalent. It is possible the name does not survive at all, or it survives in an unrecognized form. Given the distances, however, and suggestions of various authors, I’ve looked at three different areas. Personally, I like our third location, which actually puts Fumi up along the coast, near Munakata. Munakata shrine is associated with the island of Okinoshima. Sitting out in the Korean straits, this island is considered sacred, and the entire place is a shrine. Not only that, it has been a shrine since at least Yayoi times. And on the mainland there are numerous kofun—old mounded tombs—that appear to be associated with it. Though many of the kofun are later than Queen Himiko’s time, they nonetheless indicate areas that were considered important—likely the population centers. After all, the elites would want people to see their tombs—though some were put in rather out-of-the way places.

Zuma, Toma, or Izumo?

Another question we have is that of Toma or Zuma. Again, we need to remember that “Zu” is a voiced “Tu” (aka “Du”). So Tu/To is not as far off. Likewise, the “zu” of “Izumo” is a voiced “Tu”. It is easy to see, then, how “Toma” might have come from (or become) “Izumo”, and the population described certainly fits with what we know of the area. Izumo was a counter to Yamato in many of the old stories, not quite falling fully under Yamato hegemony until much later, despite the way the Japanese chronicles tell the story. We’ll look at this more fully, later.

Still, there are other candidates. The land that eventually became Kibi may have some claim to it, and similar areas along the Seto Inland Sea. Still, given what we know of the area up in Izumo, that seems the logical choice.

Pronunciation

Below is a list of the names of the lands that come up in the podcast. First is the original Chinese characters, and then we see the pronunciation suggested by Tsunoda, Kidder, Soumare, and Bentley. These all are versions of the names that you might run across, Bentley’s providing perhaps the accurate reading, though with a transcription that may leave many non-linguists confused. Still, I think you can get the gist:

| Land | ||||

| Original | Tsunoda | Kidder | Soumare | Bentley |

| 带方 | Tai-fang | Daifang | Daifang | |

| 韓 | Han | Han | Han | |

| 狗邪韓 | Chü-ya-han/Kou-ya-han | Kuyahan | Gouxiehan | *koya-kar(a) |

| 對馬 | Tsushima | Tsushima | Tsu-ma | *tǝsVma or *tusVma |

| 一大 | "Another large country" | Iki | I-ki | *ike |

| 末盧 | Matsuro | Matsura | Matsu-ro | *mat-rɔ |

| 伊都 | Izu | Ito | I-to | *itɔ |

| 奴 | Nu | Na | Na | *nɑ |

| 不彌 | Fumi | Fumi | Fu-mi | *pume |

| 投馬 | Toma | Toma | Zu-ma | *toma |

| 邪馬壱・邪馬壹 | Yamadai | Yamatai | Ya-ma-tai | *yama-tǝ(ɨ) |

| 斯馬 | Shima | Shima | Shi-ma | *sema |

| 已百支 | Ipokki | Ihaki | I-ha-ki | *kɨpa-ke |

| 伊邪 | Iza | Iya | I-ya | *iya |

| 都支 | Tsuki | Toki | Ta-ki | *tɔke |

| 彌奴 | Minu | Mina | Mi-na | *menɔ |

| 好古都 | Kasoto | Kokoto | Ko-ka-ta | *hokɔ-tɔ |

| 不呼 | Fuku | Fuko | Fu-ko | *puhɔ |

| 姐奴 | Shanu | Sona | Sa-na | *sanɔ |

| 對蘇 | Tsutsu | Tsuso | Tsu-sa | *tǝsɔ or *tusɔ |

| 蘇奴 | Sonu | Sona | Sa-na | *sɔnɔ |

| 呼邑 | Koyi | Ko-o | Ko-yū | *hɔ-ipV |

| 華奴蘇奴 | Kenusonu | Kanasona | Ka-na-sa-na | *wanɔ-sɔnɔ |

| 鬼 | Ki | Ki | Ki | *kui |

| 爲吾 | Iigo | Igo | I-go | *wai-ŋgɔ |

| 鬼奴 | Kinu | Kina | Ki-na | *kui-nɔ |

| 邪馬 | Yama | Yama | Yama | *yama |

| 躬臣 | Kushi | Kuji | Kyū-jin | *kuŋginV |

| 巴利 | Hari | Hari | Ha-ri | *pari |

| 支惟 | Kiwi | Kii | Ki-i | *kewi |

| 鳥奴 | Wunu | U-a | A-na | *ɔnɔ |

| 奴 | Nu | Na | Na | *nɔ |

| 狗奴 | Kunu | Kona | Ku-na | *konɔ |

Kyushu v. Kinki

In the podcast, I’m not going to spend too much time on the subject of whether Yamato is in Kyushu or in the Kinki region—the area around Osaka and Nara. We may get into the evidence for the Makimuku area and the Hashihaka kofun, but I do want to at least acknowledge that there are those who believe that “Yamatai” was actually in Kyushu, and that Yamato was a later state in the Kinki region.

There are a variety of reasons as to why people insist that Himiko was Queen of a country in Kyushu. Some of it is political: There is no “Queen Himiko” in the official imperial lineages. Therefore, she couldn’t have been the ruler of Yamato. Therefore her country, which would, in modern on’yomi, be pronounced Yamatai, must have been somewhere else. Since many of the early mounded tombs are in Kyushu, and they were closest to the mainland, surely that is where she must be from?

Then there are finds like Yoshinogari. This is a large settlement with moats, a stockade, towers, and even a large, raised “palace” structure, which comes from around the time of the Weizhi. For many people it is proof that Queen Himiko must have come from this area, since nothing else has been found that quite matches it. However, it is hard to find any way that the set of instructions we are given matches up with Yoshinogari, and the site is much too small—only around 2,000 or so population. While the Chinese chroniclers may have exaggerated some numbers, it is a far cry to go from 70,000 households down to a population of about 2,000.

More likely, Yoshinogari is impressive because it survived—it was out of the way and wasn’t built on top of and plowed under over the centuries of land cultivation, which is what would have happened in most of the more populous areas of Japan. While there is no guarantee that a once populous area would remain so, it does seem likely that an area that once housed over a quarter million people would be one of the areas that even today house a lot of people. Indeed, near the Makimuku area they have many mounded tombs, including the largest of the keyhole tombs, Hashihaka, from this period, and they have found the remains of what appears to be a palace. While the current construction around the area makes it hard to do further archaeological study, it seems promising that there may once have been a large, thriving Yayoi and early Kofun population in this area. Time may tell.

For now, most scholars appear to be leaning towards the region near Osaka and Nara, and that is where we will look for answers, at least until something better comes along.

References

TORRANCE, R. (2016). The Infrastructure of the Gods: Izumo in the Yayoi and Kofun Periods. Japan Review, (29), 3-38. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/44143124

Barnes, Gina L. (2015), Achaeology of East Asia: The Rise of Civilization in China, Korea and Japan

KO, Kyoungsoo. (2011?) “Ritual Sites and Ritual-Related Artifacts in Korea for Comparative Study for the Positioning of Rituals in Okinoshima Island”; http://www.okinoshima-heritage.jp/files/ReportDetail_70_file.pdf

TAWARA, Kanji. (2009, Nov), “Tsushima as ‘boundary’”; Bulletin of the Society for East Asian Archaeology 2: 19-22

Bentley, John R. (2008), “The Search for the Language of Yamatai”. Japanese Language and Literature (42-1). 1-43. Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org/stable/30198053

Soumaré, Massimo (2007), Japan in Five Ancient Chinese Chronicles: Wo, the Land of Yamatai, and Queen Himiko. ISBN: 978-4-902075-22-9

Kidder, J. Edward (2007), Himiko and Japan's Elusive Chiefdom of Yamatai: Archaeology, History, and Mythology. ISBN: 978-0824830359

Kyodo. (2000, Nov 04) “Archaeologists unearth settlement mentioned in Wei Chronicle”; https://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2000/11/04/national/archaeologists-unearth-settlement-mentioned-in-wei-chronicle/#.XiI9r2hKiUk

Barnes, Gina L. (1988); Protohistoric Yamato: Archaeology of the First Japanese State;

Hudson, M., & Barnes, G. (1991). Yoshinogari. A Yayoi Settlement in Northern Kyushu. Monumenta Nipponica, 46(2), 211-235. doi:10.2307/2385402