Previous Episodes

- June 2025

- May 2025

- April 2025

- March 2025

- February 2025

- January 2025

- December 2024

- November 2024

- October 2024

- September 2024

- August 2024

- July 2024

- June 2024

- May 2024

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

This episode is focused on discussion of the recent paper “Ancient genomics reveals tripartite origins of Japanese populations” by Cooke, et al, which many people are claiming is “re-writing” ancient Japanese history. But what history is it re-writing and what do their findings mean for us, going forward?

Geography

So first off, there is a lot of talk about various locations on the mainland that we don’t normally cover, so we’ll have some maps here to help out.

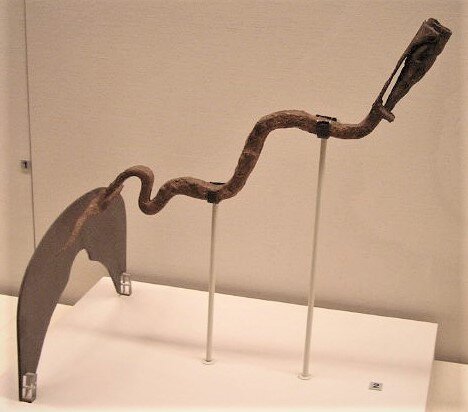

So one of the places we will be discussing is the West Liao River Basin. The Liao river runs into the Yellow sea on the western side of the Liaodong peninsula (in fact, Liaodong can be translated as basically “east of Liao”). The River Basin includes the various rivers and tributaries that flow into the Liao River and then on into the ocean. Three of the individuals from the continent that the researches compared DNA to were from the Longtoushan site, a bronze age site in the West Liao River Basin, hence the nomenclature of WLR_BA and WLR_BA_o. The first referring to the two individuals with significant DNA matches to populations in the Yellow River Basin while the second referred to the one individual with DNA that indicated ancestry in the Amur River Basin. This was the individual who most closely matched with the Yayoi samples on the archipelago.

Map demonstrating possible gene flows during various periods based on the most recent findings. An attempt has been made to show the possible maximum extent of the ancient shoreline, when the archipelago and the continent were directly connected, which likely lasted until maybe 16,000 years ago, or even earlier, about the start of the Jōmon period, where populations show signs of extreme isolation.

This next map is extremely general, and shows what seems to be the general gene flow into the archipelago, based on the latest research. There is a flow that comes from Southeast Asia up north and into Japan from the earliest period of migration, which likely happened from ~38,000 to ~16,000 years ago. Then there is gene flow detected from what seems to be the Amur River Basin, possibly passing through Western Liao River Basin before making its way to the islands around the time of the Yayoi, about ~3,000 years ago—around 900 BCE, when rice first starts to show up as a crop on the archipelago. Finally, we have gene flow from the Yellow River Basin sometime between the Yayoi and the late Kofun period, between roughly the 3rd and 7th centuries CE. By the end of the Kofun the genetic makeup of the Japanese population appears to be fairly stable up through the modern day, with only slight variation as compared with earlier populations.

Previous Episodes

If you want to go back and listen to some of the episodes that may be relevant to the discussion, here’s a brief, non-exhaustive list:

Episode 1 - Pre-historic Japan

Perhaps a bit of a misnomer since we stayed in pre- or proto-history for quite some time—many even still count proto-history up until the actual publication of the Chronicles themselves. Anyway, in this first episode we talked about Minatogawa Man and the earliest traces of homo sapiens on the archipelago, including how they may have got there.

Episode 5 - Goggle Eyes and Wet Earwax

Episodes 2 through 5 were all about the Jōmon, and in our fifth episode we talked about what we learned from the DNA sequencing of the woman from Rebun island, off the coast of Hokkaidō. She is one of the previously sequenced genomes that this study used in their research and analysis.

Episode 7 - Rice comes to Japan

Though we touched on some of the continental movements in Episode 6 and the birth of rice agriculture in the Korean peninsula, Episode 7 is where we really see rice coming over to Japan and the start of the Yayoi period. This is presumably when the Amur River ancestry makes its way into Japan.

Here is where we discussed the establishment of Lelang and the various Han commanderies on the Korean Peninsula, though it is at the very end of the episode. The fact that the commanderies were established in 108 BCE, though, means that while they could have brought Yellow River DNA with them, it was much too late for the first wave to cross over to the archipelago about 800 years prior.

Episode 9 - The Langauge of Wa

This is one area where I think we definitely have some questions to ask ourselves. If the early Yayoi were people with Amur River ancestry, then did they bring the language of “Wa”—that is to say, Japonic—with them or did the origins of Japanese in the archipelago come later? It is still possible that there is a link to the Shandong peninsula, but if so, perhaps the Japonic language families didn’t come in until some time after people with Yellow River Basin ancestry arrived. We certainly see traces of what looks to be Japonic in the names used for the countries of Japan in the mainland accounts, so it would seem to have been established by that time, but who brought it to the islands, and when?

Episode 30 - Yamato and the Continent

For about 21 episodes we covered the Age of the Gods and various legendary—possibly mythic—sovereigns, finally coming back to the connections with the continent—something that we touched on throughout, but here we talked about some of the evidence in the Chronicles pointing to emigration from the peninsula from a very early period.

Episode 39 - Birth of the Three Kingdoms

This was the episode we concentrated on what was going on over on the mainland, including the destruction and collapse of the commanderies, leading to an apparent diaspora of the ethnic Han citizens across the peninsula and over into the archipelago.

-

Welcome to Sengoku Daimyo’s Chronicles of Japan. My name is Joshua and this is episode 50: New Research On The Origins Of The Japanese Population.

Before we get started, quick shout out to Poser27 for your support. If you’d like to join them, feel free to drop us a few dollars over at ko-fi.com/sengokudaimyo. That’s K-O-DASH-F-I-DOT-COM SLASH “Sengokudaimyo”.

Now this episode is a bit special: we’re taking a break from the Chronicles to talk about a breaking piece of research, a new study just published by a team of scholars out of Trinity College, in Dublin, as well as many others from around Japan. You may, if you follow the right hashtags, have seen some flashy headlines about this, such as “Ancient DNA rewrites early Japanese history”—a pretty bold claim. So this episode I would like to dig a bit into this study itself, how it connects to what we’ve been talking about in the podcast about the changing population of Japan, and hopefully get beyond the clickbait.

And, since it’s Episode 50 – wow, time flies! – and we’re referring back to some topics we’ve already touched on, I’m going to feel free to name-drop earlier episodes to provide you a handy guide to where to find a refresher on anything we’ve already talked about.

A few caveats up front as we get into this: First off, you are mostly getting my take, as discussed with my lovely wife and editor, based on our reading of the study, various articles, and Twitter threads by scholars who know their stuff about Japanese history, so I’ll try to have links to all of that in the show notes at up at Sengokudaimyo.com/Podcast. Second, though I want to dig into the article, I make no claims at being a geneticist. I will be trying to do this without directly discussing things like haplogroups and the statistical functions used to compare ancient genomes. These are accomplished scientists and this is a peer reviewed paper, so I am taking them at their word. Rather than looking at the science of the genetic research, I want to see how their conclusions match up with what we think we know about early human activity on the archipelago in the pre- and proto-historical eras.

The study itself was published in the Journal “Science Advances”, which is a well-respected, open-access, multidisciplinary journal published by the American Association for the Advancement of Sciences. If you’ve heard of the journal “Science”, these are the same people and they’re legit. The study, which came out on 17 September, is called “Ancient genomics reveals tripartite origins of Japanese populations” - we’ll have a link to the article itself up on the website, at sengokudaimyo.com/podcast.

The study reported out 12 newly sequenced ancient Japanese genomes, and compared all of them with each other, and other previously-known genomic data from Japan as well as the continent. Their findings would appear to indicate three different contributors to the DNA of modern Japanese populations: Jomon and Yayoi contributions are unsurprising, but they noted a third contributor showing up by the late Kofun period.

So is this a big deal, and if so, why? Let’s go back to the source and talk about the whole practice of tracing the origins of the people of the Japanese archipelago.

As you may have gathered, this has long been a part of Japanese historical studies. Heck, even the 8th century Chronicles that we read were making attempts to do that very thing by ascribing a divine origin to the creation of the islands and the descent of its people—or at least of the ruling elite.

For the longest time, this was *the* history of the archipelago that people followed, and though it does speak of various people coming over from Korea, and families who claimed descent from either Korean or Chinese families, the general assumption appears to be that those immigrants were assimilated into a much larger and uniquely Japanese population that maintained its links to that original heavenly descent.

In the late 19th century, though, archaeology was added to the mix, providing a means to place various artifacts into an historical context. In some cases this helped confirm what written sources had to say, but in others it just brought up more questions. Jomon and Yayoi pottery weren’t necessarily new—no doubt farmers and others had been digging them up for centuries—but with new tools and concepts of how to date and categorize the finds, the history of the archipelago exploded. While the Kofun period had always been apparent—after all, giant mounds of earth in distinct keyhole shapes, often moated, are hardly inconspicuous—the addition of the Jomon and Yayoi periods not only added more context, but they pushed back the boundaries of when people had arrived on the archipelago. Instead of history starting in the already fanciful 7th century BCE, the Jomon period and other prehistoric finds pushed the early date of human habitation back to about 38,000 years ago. We discussed this, and briefly covered the Jomon people in the first five episodes back in 2019—we’ll have links on the site so you don’t need to comb through the archives to find them.

Further studies showed a distinct change with the advent of rice farming. Originally thought to have been about 300 BCE, that date has since been pushed back to about 900 BCE. During the Yayoi we see rice, bronze, and new lifeways entering the archipelago. There was a lot of debate about where all of this came from, with strong indications that it arrived from the continent via the Korean peninsula, though some theories did suggest a southern route, up from south China and Taiwan. At this point, though, I think we can fairly confidently assert clear influence from the Korean archipelago during this period.

That said, the prevailing theory even with this new archeological evidence was that the people of the archipelago had not significantly changed. That is, the idea still held that the Japanese people themselves were established in the archipelago some 38,000 years ago and that, though they may have acquired technology and other cultural goods from abroad, they were essentially the same people. Of course, in this one might also see shades of discussions of things such as race, prevalent in the early 20th century, and the idea that the Japanese were somehow unique and distinct from the rest of Asia was definitely a view pushed by nativists and nationalists, who were seeking reasons to tout Japan’s superiority over other people.

However, much to the nationalists’ dismay, further archaeological studies demonstrated that there was not only a cultural change, but a demographic one as well. Skeletal remains from the Yayoi period demonstrate different morphological features that seemed to indicate at least two different groups of people existing in the islands at the same time. One group was more similar to the Jomon and ancient people of the archipelago, wile a second group was more closely related to the people of the peninsula and the continent—as well as modern Japanese.

Some people tried to push the idea that this was just part of the natural changes that could occur in populations over the years. After all, just between the Edo period and modern times a distinct change can be detected in the average height of Japanese people, largely attributed to things like changes in overall health and diet. However, more and more people questioned this idea, especially given the presence of the Ainu, in the north of the archipelago, a people who appeared to share more physical similarities to the earlier Jomon people, at least in regards to skeletal dimensions. Furthermore, it was in the north of the archipelago where the Jomon culture continued and evolved into the epi-Jomon, while in the central part of the archipelago the Yayoi culture was thriving. Later DNA tests demonstrated that there was an ancestral link from the Ainu to ancient Jomon populations, though intermixed with other people of the Okhotsk Sea region.

From this type of research emerged the idea, now generally taught in textbooks: The islands had been populated by the early Jomon people, but then a new group came in and, through the use of technologies like rice farming and new bronze, and later iron, weapons, were able to soon supplant or assimilate the previous inhabitants of the archipelago. This idea that modern Japanese are a mixture of these two populations—the earlier Jomon people and the later Yayoi, a group who came over during the Yayoi in one or multiple waves – is called the dual origin theory of the modern Japanese population, and it was largely solidified through the ideas of Hanihara Kazuro, who wrote about it in Japanese in the 1980s and then later published in English in 1991. Some of the Jomon people who didn’t assimilate into the new ethno-culture complex on the islands became ancestors of the Ainu, in the north, mixing with other groups in and around the Okhotsk and Japan sea regions, but the rest mixed with the North Asian population.

Where this wave of Yayoi immigrants ultimately came from—beyond the obvious answer of the southern Korean peninsula—has been a question for some time. Many of the early studies were based on various physical characteristics of the Yayoi and later Japanese, many associated with cranial dimensions—that is the specific dimensions of the skull. By the way, the origin of these studies, known as craniology, have a particularly nasty past, having to do with Eurocentric theories about the existence of racial characteristics as well as attempts to measure skulls against so-called Caucasian traits to determine some kind of racial hierarchy. While the racial underpinnings of craniological research have been discarded by modern anthropologists, it can still be a useful tool for distinguishing potentially different populations, particularly in a paleo-anthropological context, and so the these kinds of physical measurements continue to be used today for description, rather than classification.

From those kinds of studies, it was determined that the Jomon were associated with traits found in Southeast Asia, and were assumed to have come from South Asia during paleolithic times. The Yayoi were associated with traits more common in North Asian populations—and specifically Northeast Asian populations.

Now, linguists have largely assumed that these immigrants to the archipelago are the source for the Japonic languages. After all, cultures associated with Yayoi or later, such as the Japanese and Ryukyuan populations, speak some form of Japonic, while the Ainu language is its own thing, possibly connected to a language spoken in the archipelago prior to the spread of Yayoi culture.

Given this connection between Japonic languages and Yayoi culture, linguists searched out the roots of the language and some have looked at these findings in the context of what we knew about the coming of the Yayoi people—people that were likely the Wa of the ancient Chinese chronicles. Some scholars connected the Japanese language to Koguryoic, the language family of Korean, identified with the people of Goguryeo and the Buyeo people, among others. This in turn was connected to larger “transeurasian” language families.

More recently there has been some suggestion that proto-Japonic may have come over to the Korean peninsula via the rice cultivating cultures of the Shandong peninsula. Under that theory, any similarities between the Japanese and Korean languages are more likely related to their many centuries of close interaction, rather than an actual direct link between them.

All of this linguistic work seemed to enhance the idea that a large group of people came over in the Yayoi period, further emphasizing this concept that the Yayoi was, in a way, the “birth” of the Japanese people—that it was these two groups, the Yayoi and the Jomon, coming together that gave rise to the Wa, the ancestors of the modern Japanese population.

Of course, besides skeletal morphology and linguistics, this brings us up to one other category of evidence, something we’ve brought up in previous episodes and which is the subject of this latest study, and that is DNA. Unfortunately, as I’ve mentioned before, the Japanese soil doesn’t tend to be the best for preservation of organic material. It tends to be more acidic, and so many times human remains are hard to find. Still, to date there have been enough bones and bone fragments found for scientists to start to build a picture of ancient genomes. For instance, in our first episode we discussed the pre-Jomon era Minatogawa Man, down in the Ryukyu Islands, and back in Episode 5 there was the Jomon woman up in Hokkaido whose genome told us, among other things, that people in the Jomon period had already developed a tolerance for alcohol..

Most of those genetic studies have been largely focused on individuals found in a Jomon context or earlier—so pre-Yayoi immigration. When compared with modern Japanese, we find that there are certain genetic markers in modern populations that would seem to trace back to those early Jomon populations. This correlates with some of the physical data as well, suggesting traits of both north and south Asian populations are found heterogeneously in the modern Japanese population. This information is important because it suggests that the Jomon were not simply conquered and wiped out, but that, as some of the archaeological evidence has suggested, they were assimilated and incorporated into Yayoi society.

There are also studies that looked at the current Japanese population and where they had the most affinity with the people of the continent. Those studies seemed to confirm an affinity, along with modern people on the Korean peninsula, with the larger East Asian population, including the ethnic Han people and the Yellow River Basin.

Of course, that would make sense if the dual origin theory was correct: A wave of people coming over from the continent, bringing with them wet rice agriculture. Since that rice agriculture seemed to have a basis in the Yellow River or nearby Shangdong peninsula regions, we seem to have a nifty line connecting language, culture, and people. The Yellow River basin is part of North Asia, and so, even if it was multiple, successive waves of people coming over from the continent, the implication is that they were largely the same people.

So, that’s a summary of the prevailing theory: the dual origin hypothesis, which makes sense given the archeological, linguistic, and genetic evidence available to date. But this new study has provided some evidence that sets some of this – not all, but some - in a new light. Though it largely supports previous theories, it raises some interesting questions.

First off, this latest study has increased our understanding of the changes in the genetics of the Jomon people. The study reports out an unprecedented 12 new genome sequences—nine of whom were from individuals buried in a Jomon context. Together with previously sequenced genomes, the team has been able to determine several things.

First, the Jomon DNA that was studied demonstrates attributes that are strongly associated with the modern populations in the Japanese archipelago, but are otherwise rare on the continent. All of the Jomon individuals studied formed a tight cluster when compared with other populations, suggesting that they had, indeed, been largely isolated—otherwise we would expect to see more similarities between them and the continent. This is consistent with the idea that, as the glaciers receded and the oceans rose after the last glacial maximum, it left a population of humans stranded on the archipelago. These people, who may have been part of a lineage of hunter-gatherers who came north into East Asia from Southeast Asia some time prior would be the people we would come to know as the Jomon. And while genetic isolation is not quite the same as cultural isolation—we find, after all, evidence of cross-strait commerce—this does seem to fit with previous theories of early life in the Japanese islands.

Now in addition to the Jomon DNA, the study looked at five examples of post-Jomon DNA. Three of those were newly sequenced DNA from Kofun era individuals who were all buried in the same general area, south of the Noto peninsula. Two of the individuals were previously sequenced in other studies, and were found in a late Yayoi context in Northwest Kyushu and demonstrated a physical resemblance to Jomon people. What is a bit surprising, and what is driving those dramatic headlines, are both the differences between these Yayoi and Kofun individuals, and the fact that the Kofun era individuals group extremely well with modern Japanese, suggesting much less change between the Kofun and today than between the Yayoi and the Kofun period.

So what does this mean for the dual origin hypothesis? If if was the Yayoi immigration that largely shaped the genetics of modern Japanese, why do we see such differences in the genetic samples between Yayoi and Kofun?

One possible explanation for this could simply be that there was continuous immigration to the islands from the Yayoi into the Kofun period of state formation. So rather than a single wave of Yayoi era farmers coming over and setting up shop in the archipelago, that suggests to me the idea that continuous waves of people may have been coming across at various times. This would be in line with an extension of Hanihara’s dual structure hypothesis, as well as what we know from the Chronicles.

However, the DNA situation here suggests that it is a bit more complex. The Yayoi samples from the study definitely contain significant contributions from the Jomon people in the study, but there is also another contributor that’s a bit surprising. Given that the Yayoi is when rice farming appeared, we might expect that this other contributor might be from individuals tied to the Yellow River Basin, which is thought to have been the source of rice farming culture that made it to Japan and kicked off the Yayoi period. However, the two individuals sampled showed little affinity to the Yellow River Basin. Where the study’s authors did detect some kind of connection was with a genetic sample from the non-rice farming people of the West Liao River Basin, which stretches from Inner Mongolia to the border of North Korea, sits northwest of the Korean peninsula and northeast of the Yellow River Basin. More specifically, these individuals were from a site known as Longtoushan, near the village of Tuchengzi, Chifeng, in Inner Mongolia

In fact, this West Liao sample consisted of three individuals from the same archaeological site but with fairly diverse genetics. Two of the three individuals studied had genetic ties to the Yellow River Basin area. For those looking on a map, the Yellow River is the large river that empties into the Yellow Sea, between modern Chinese mainland and the Liaodong and Korean Peninsulas – so really, not that far of a hike from Japan. But the third had a greater connection to people of the Amur River basin, which makes up the northern most border between the People’s Republic of China and the Russian Federation, for the most part significantly north of modern Japan and Korea except at the very northern edge of the Korean peninsula.

Of those West Liao individuals, it was the one with Amur River genetic affinity, not the two associated with Yellow River populations, that had a high genetic affinity with our Yayoi samples. This suggests—at least given the current data—that the Yellow River basin was not likely to be a major source of the non-Jomon ancestry in these two Yayoi individuals, which somewhat violates our expectations. Rather, it is with people more associated with the Amur River region.

The study’s authors further tested several potential sources of continental ancestry, creating hypothetical mixtures of their DNA with that of the known Jomon DNA. These were all groups who shared a dominant Northeast Asian component to their ancestry. In the end, the Yayoi seem closest to individuals of the middle Neolithic and bronze age from the West Liao River Basin who also had a high level of Amur River ancestry, and the West Liao River Basin is just north of one of the supposed routes that rice agriculture took, from the Shandong peninsula, down the Korean peninsula, and to the archipelago. And so it isn’t out of the question that there were some people with northeast Asian ancestry, and specifically Amur River ancestry, who were part of the wave pushing that technology across the early Korean peninsula and then to the Japanese islands.

In contrast, the three individuals who had been buried in a Kofun context, hundreds of years later, tell of a different story. In their case they are much closer to modern Japanese. They don’t show the specific traits that linked the Yayoi to the Amur River basin - instead they show a much greater affinity with people of the Yellow River and, in fact, to much of the rest of east Asia.

And so the story that is emerging from all of this is that it seems there was one wave of immigrants that came over with the Yayoi, as already expected, but then there was at least one more wave of immigrants that came over around the time of state formation. It is even possible that there were other, successive waves.

By this time, if you’ve been following the podcast, you might be saying: Well, yeah. The Chronicles themselves talk about numerous people coming over from the Korean peninsula, including elites who married into the royal line. However, this isn’t exactly the narrative we get in all the histories. Usually it is just: People arrive, get isolated on the islands, and start making pottery with cord markings. Then a new group of people arrive, bringing rice and bronze and iron. They build up their settlements and eventually we get Queen Himiko, the shaman queen. From there, a big question mark, people start building giant, kingly tombs. That becomes a fad and then we get state formation. Hurray! Japan!

Okay, maybe not quite that simplistic, but I think you get my drift.

The DNA from this study supports some the theories and evidence that exist outside this long-standing official narrative. We can point to the change in material goods, and even what the written histories have to tell us, but this really gives us another data point to go off of, and hopefully we will get more.

And while many are quick to point out that this overturns the dual structure hypothesis, I would argue that it more refines it. Where Hanihara had originally had two sources for the origin of the Japanese population, South and North Asia, respectively, his models don’t rule out the possibility of multiple waves of immigration from different parts of north, northeast, and east Asia.

Now, quick caveat time—the Yayoi samples come from two individuals, from the same location, in Northern Kyushu. It is entirely possible that these two individuals happen to be outliers, though I would note that they contain a mixture of Jomon and external genetic markers, such that they are unlikely to be just off the boat. Furthermore, since they determined that none of the individuals in the study were related, that would indicate that there were at least two descendants from the initial mixing—probably several generations. Likewise our three Kofun samples come from the same area, and they were not occupants of keyhole shaped tombs, so they may be of some status, but they weren’t the elite running the country, and, again, the sample size is limited.

There is still a lot we don’t know. We don’t know how all of this information on genetic diversity matches up with stories of the Emishi, the Tsuchigumo, the Kumaso, or the Hayato—some of the ancient groups of the archipelago—possibly different ethnicities. We don’t know if the ancestry of the people in the mountains was different from those in the plains and farmland. And it would be especially interesting to see comparisons with various people on the Korean peninsula.

But given what we do know, at this point, what does it tell us?

Well let’s go back to the information about the Amur River connection to our two Yayoi individuals. We know that farming came across 900 BCE—about 600 years earlier than was previously thought, even 20 years ago, and there are *still* sources that have it start at 300 BCE or later, even today. In 900 BCE, from what we can tell, there wasn’t much Han presence in the peninsula region, and so it makes some sense that the people coming across would be more broadly connected with Northeast Asia, even though the West Liao River basin seems to have been a mixing pot of various people.

Unfortunately, from what I can tell, we seem to have a gap on the Korean peninsula itself. There have been various studies on the modern Korean population and trying to link them to various ancient ancestors, but I’m not sure that there is much in the way of paleo-genetics for the peninsula between the Yayoi and Kofun periods. While later studies confirm a relationship between Korean, Japanese, and ethnic Han populations, it seems that this relationship is assumed to generally extend back into the distant past.

But if we have another population coming to the archipelago in the Yayoi, then one assumes that the peninsular people were similarly different, at least in that early Neolithic and bronze age period.

I suspect this could be explained by the creation of the Han commanderies on the peninsula in 108 and 107 BCE, which we first discussed back in Episode 8. I suspect that a large number of ethnic Han immigrated to the peninsula at this time. It is possible that some intermarried with local populations, bringing in new genetic source material to the peninsula.

And then, in the early 4th century CE, we see the destruction of the commanderies by Goguryeo, and soon thereafter we see written culture arising in places like Silla and Baekje—possibly brought with an influx of ethnic Han fleeing Goguryeo and the destruction of the commanderies. Lots of population churn during this period, as we discussed in Episode 39.

There are still some important questions to be asked in terms of timing. We know that the Kofun era individuals in the latest study closely resemble modern Japanese, bringing in a much higher proportion of East Asian DNA. But when did that happen? The study says that the specific Kofun individuals were from about 1300 years ago. That actually puts them towards the end of the Kofun period. So we can see that change happened between the Yayoi and the end of the Kofun, but we still have a question of when.

Was there immigration during late Yayoi? Is that what led to the creation of the giant keyhole tomb mounds? That is one of the defining features of the Kofun period, so it could be a logical leap.

I would note, however, that there were already mounded tombs in the islands in the Yayoi period, in the form of funkyubo. Based on that, we don’t exactly need an external explanation for the arrival of mounded tombs, unless it came even earlier in the Yayoi period. The earlier, simpler tombs could have locally evolved into more complex practice along with changes in social complexity, the role of elites, and so on.

On the other hand, perhaps the kofun were part of the later migrations that were happening. Proponents of Egami’s horse-rider theory might point to this as another piece of evidence supporting their supposed conquest of the islands: A large group sweeping south. Of course, that theory suggests that those same riders were part of a general Buyeo ethnic group moving south, from Goguryeo to Baekje. But I wonder how that squares with the higher genetic connection to the Yellow River Basin? After all, the Buyeo and Goguryeo populations were likely more connected to other northeast Asian populations, themselves.

Perhaps this is all just was increased emigration over the course of the Kofun period, especially if the Wa people had some foothold on the peninsula, providing an entry point to mix and travel back and forth. Could it be that simple? Greater contact with the continent, and with the peninsular kingdoms, and more people coming over—enough to significantly affect the gene pool on the archipelago.

One thing is certain: We need more of this kind of research. Not just the new tools of DNA analysis, but the application of various big data techniques to draw out relationships. It then needs to be incorporated into our understanding of the past. In the last decade, the tools and methods for this kind of data to be collected and analyzed have been refined and expanded, and I expect to see more of it.

So what are the lessons we should take away from this whole thing?

Well, for one, if you see a dramatic headline, check your sources—and then check the sources behind what you are reading. The Internet, for one, is horribly mixed up. There are plenty of places that will still cling to old sources. And sometimes it takes a while for the latest research to show up in a form that is easily accessible to most of us. Even here in this podcast I’m trying to do my best to accumulate current research but it isn’t always an easy task, especially for an independent scholar outside of the academic system. One of the reasons I try to give you my sources is because then you can check them out yourselves and take a look at the date on the information.

Now, it isn’t the case that newer is always better. Sometimes new theories don’t pan out, but that is a decision you can make on your own.

For another thing, I think this study provides another piece of clear evidence of the complex relationship between the archipelago and the continent, with multiple waves of immigration coming over, bringing new people, new technology, and new ideas. Although we often talk about the insular nature of the Japanese archipelago, more and more we can see that they were actively involved with the continent in trade, politics, and populations, and the Kofun period was a particularly dynamic time.

For example, in the same week that this article on ancient Japanese DNA was posted, we got word that in a Yayoi era kingly tomb in Fukuoka, northwest Kyushu, were found glass beads which seem to have originated in the Mediterranean region of the Roman Empire. Similar beads were also found in Mongolia, and based on scientific studies they appear to have come from the same place, meaning that glass beads traveled from the Mediterranean all the way to Japan via Mongolia and the central steppes of Eurasia.

And this isn’t entirely new. Exchanges between Asia and the Mediterranean have long been known, traveling through trade networks and handled by individuals traveling the long routes from one side of Eurasia to another. Most of their journeys aren’t captured in any writings or histories, but their imprint and impact can surely be felt. This is something we will talk about as we see more things coming across, but it is always good to keep in mind that it isn’t just the modern world that is incredibly connected—and Japan has long been a part of that connected world.

Next episode we’ll bring the focus back around the Chronicles and the stories therein. We are going to look at the stories of Oho Sazaki no Mikoto, aka Nintoku Tennou, and his court in Naniwa—modern Ohosaka.

And that’s all for this episode, until next time, thank you for all of your support. If you like what we are doing, tell your friends and feel free to rate us on iTunes, Spotify, or wherever you listen to podcasts. If you feel the need to do more, and want to help us keep this going, we have information about how you can donate through our KoFi site, kofi.com/sengokudaimyo, or find the link over at our main website, SengokuDaimyo.com/Podcast, where we will have some more discussion on topics from this episode.

Also, feel free to Tweet at us at @SengokuPodcast, or reach out to our Sengoku Daimyo Facebook page. You can also email us at the.sengoku.daimyo@gmail.com. We would love to hear from you and your ideas.

And that’s all for now. Thank you again, and I’ll see you next episode on Sengoku Daimyo’s Chronicles of Japan.

References

Cooke, N. P., Mattiangeli, V., Cassidy, L. M., Okazaki, K., Stokes, C. A., Onbe, S., ... & Nakagome, S. (2021). Ancient genomics reveals tripartite origins of Japanese populations. Science Advances, 7(38), eabh2419. DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.abh2419

Ning, C., Li, T., Wang, K., Zhang, F., Li, T., Wu, X., ... & Cui, Y. (2020). Ancient genomes from northern China suggest links between subsistence changes and human migration. Nature communications, 11(1), 1-9. DOI: 10.1038/s41467-020-16557-2

HANIHARA, K. (1991). Dual Structure Model for the Population History of the Japanese. Japan Review, 2, 1–33. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25790895

-, -. (2020). A History of Crainiology in Race Science and Physical Anthropology. The Penn Museum Website. Last viewed on 9/28/2021. https://www.penn.museum/sites/morton/craniology.php

![Takechi no [Sukune] no Ōmi on a Japanese 1 yen note from 1916.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5d1a2aa7e7ccfd0001a4f03d/1627739155754-OJSEOWQ7CJ3BU0PC2KHP/Revised_1_Yen_Bank_of_Japan_Silver_convertible_-_front.jpg)