Previous Episodes

- July 2025

- June 2025

- May 2025

- April 2025

- March 2025

- February 2025

- January 2025

- December 2024

- November 2024

- October 2024

- September 2024

- August 2024

- July 2024

- June 2024

- May 2024

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

This episode we talk about “Matsuro-koku”, the land after Iki-koku in the Gishiwajinden, and the first “country” on one of the larger islands, where the envoys would start walking from there. We are fairly certain that “Matsuro-koku” was in the area of the old “Matsura” or “Matsuura” district on the western coast of Kyushu. However, that district was much larger than the reduced “Matsura city”, today, which is really just a collection of what was left over when most of the rest of the area had been incorporated. It stretch from Hirado up past modern Karatsu, and we have reason to believe that the area around Karatsu and the Higashi-Matsuura peninsula (which is not part of modern Matsuura city) had several Yayoi era settlements, including one in the area of modern Nabatake.

Nabatake is special because it is one of the few sites where we have the earliest evidence of wet paddy rice agriculture. Today you can visit this at the Matsurokan, in Karatsu city. Unfortunately, that community did not continue into the 3rd century, when then envoys came over from Wei, but we can likely assume that the “Matsuro-koku” where the envoys landed was probably somewhere nearby. Karatsu would long be a place where people would land when coming or going from the continent, and even when better ships and navigation meant that ships could travel almost directly to Hakata, people would still stop here.

The Matsura district would largely be only a part of the larger land of Hi, later to be considered Hizen in the western part of the province under the Ritsuryo system that was the ultimate result of the changes started with the Taika reforms. Much of the written material focuses on places like the Dazai, in Fukuoka, but over time, groups in Matsura banded together, creating their own “family” of multiple factions. As Matsura is a coastal region with many nearby islands, natural bays, and the like, it is unsurprising that this “Matsura” family amassaed a not inconsequential navy.

They would find themselves in the spotlight after the Toi Invasions of the 11th century, and they continued as a local power up through the Warring States period. During the Edo period, they were granted the Hirado domain, including Iki island, and thus played a continued role in trade with the continent.

After Toyotomi Hideyoshi conquered Kyushu at the end of the 16th century, he began to look at the continent. He would eventually order the construction of Nagoya castle on the tip of the Higashi-matsuura peninsula. It was erected in months, including a five story tenshukaku, or castle keep, on the 90m high hill. This may have been helped by previous earthworks built there by members of the Matsura family. Hideyoshi ordered all of his generals to come and set up “camps” around the castle, and a bustling jokamachi, or castle town, sprung up. For seven years it was the de facto capital of Japan, with Hideyoshi using it to direct the two failed invasions of the Korean peninsula.

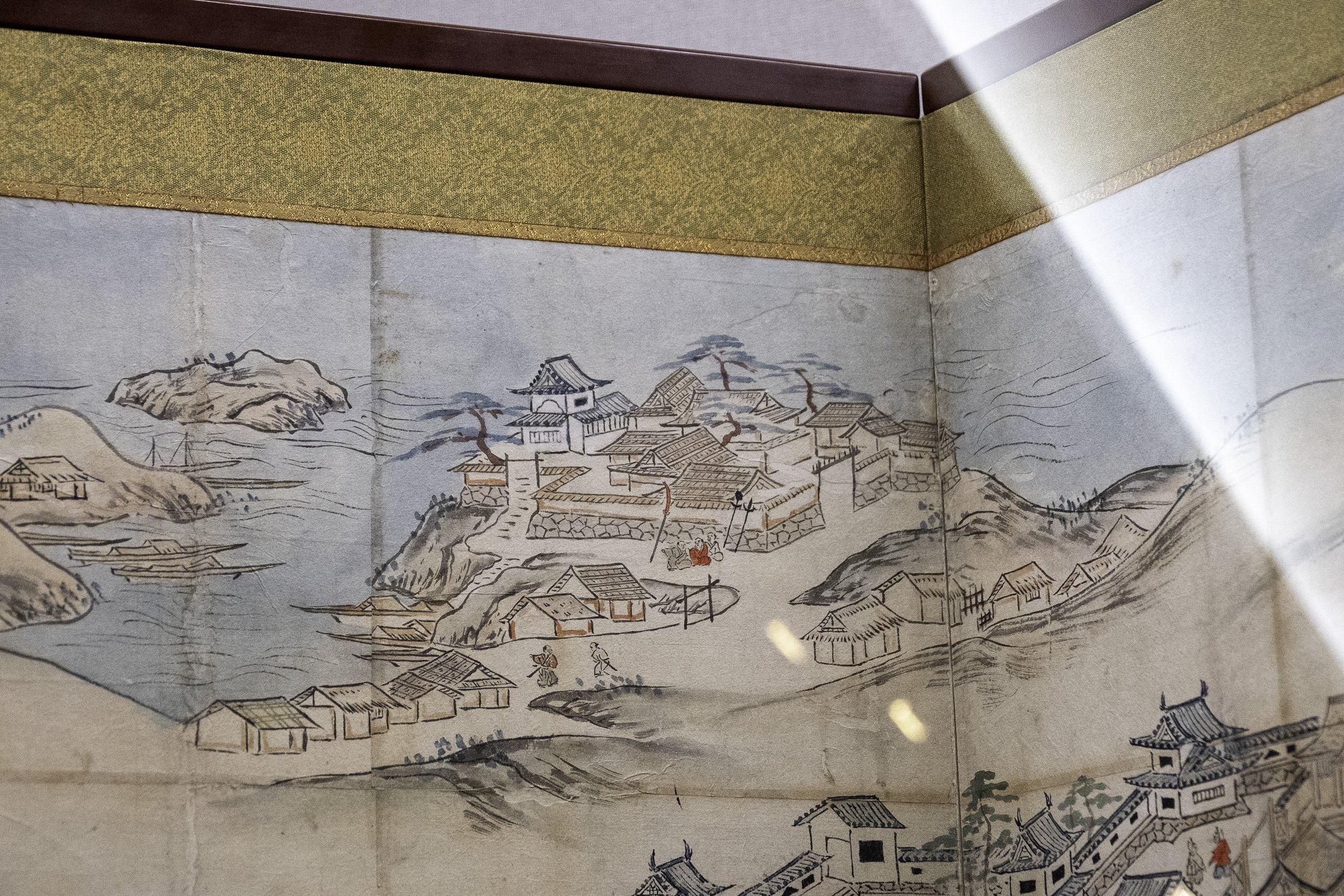

Since the town was so new, images of it show mostly thatched roofed houses, even for some of the more prominent daimyo under Hideyoshi’s command. And yet this is where Hideyoshi met Ming envoys and spent the last seven years of his life.

After he passed away, the town quickly dispersed and the castle was deliberately ruined, with key stones removed from the walls, to help prove to the Joseon kingdom that Japan was no longer seeking to invade. Focus in the Edo period turned to nearby Karatsu city.

Karatsu city had its own castle, built, in part, with some of the elements taken from Nagoya. Karatsu means “Chinese port”, indicating their role in receiving ships from the continent. Trade would be important, and the role of the daimyo of Karatsu was seen as so important that they could not be given secondary duties. This would occasionally lead to lords requesting a transfer, should they be ambitious and wish to apply for higher office within the bakufu.

In the early Edo period, a strip of pine trees was set up along the shore. This was done as a windbreak to help protect the farmland behind from storms that might blow in of the water and damage the crops. Today it is one of the oldest such groves still in existence, and it has been immortalized in story and song.

Today, the town maintains some of its traditions, and has rebuilt the tenshukaku of Karatsu castle. They also retain their “Kunchi” festival, which was modeled on that of Gion, with giant floats, now protected through UNESCO.

-

Welcome to Sengoku Daimyo’s Chronicles of Japan. My name is Joshua and this is Gishiwajinden Tour, Part Four: Matsuro-koku

So far on this tour through the locations listed in the Weizhi’s Wa Record, the Gishiwajinden, following the route to Queen Himiko of Wa, we’ve hit the area of Gaya, or Gara; Tsushima—or Tuma-koku; Iki, aka Iki-koku; and now we are arriving at Karatsu, thought to be the location of Maturo-koku.

Now before we go any further, let’s talk about the name. After all, up to this point in the account, the names haven’t been too far off. Well, Tsushima was recorded as something like Tuma in the Chinese record, which seems reasonable, and “Iki” was actually recorded as something like “I-dai”, though we are pretty sure that was a transcription error based on other evidence. But Karatsu and Maturo, really don’t seem related. Also, didn’t we earlier equate Matsuro with Matsuura, Matsura? But if you look for Matsuura on a map it is quite some distance away from Karatsu—in fact, it is in modern Nagasaki prefecture as opposed to Karatsu, which is in modern Saga prefecture.

First off, Karatsu is a later name for the city, not the area. It literally means “Tang Port”, and that name seems to appear in the 15th century in the form of Karatsu Jinja, or Karatsu Shrine. So no, the names Karatsu and Matsuro are not related. Prior to being called Karatsu, though, it was part of a larger area called Matsura. It sits at the head of the Matsura River, which spills out into what is now called Karatsu Bay. In ancient times this seems to have been the heart of the area known as Matsura or Matsuro. Over time it was incorporated into the larger area known as Hi no Kuni, and when Hi no Kuni was divided up by the Ritsuryo state into Hizen and Higo, we see the Matsura district, or Matsura-gun, is a part, along the coast. The fact that it is spelled as “Matsu” and “Ura”, meaning “pine beach”, might hint at the original name of the place or could be a false etymology, imposed by the need to record the location in kanji, the Sinitic characters used at the time.

Fun fact time: Hizen refers to the area of the land of Hi that was closer to Yamato, while Higo refers to the area of the land of Hi that was further away. If you look at a modern map of where these two ancient provinces were, however, you’ll notice that by a slight technicality, Higo is actually closer, as the crow flies. But remember, people are not crows, at least not in this life, and in all likelihood, most of the travel to and from Yamato would have been via sea routes. So Hizen is closer to Yamato from that perspective, as you would have to sail from Higo, around Hizen, or take the long way south around Kagoshima.

But where were we?

So Matsura district in Hizen started at Matsura-gawa and the area around Karatsu bay, and included modern areas of Hirado all the way out to the Goto islands. That was a pretty large area. It later got further subdivided into East, West, North, and South Matsura subdistricts, with Karatsu in the Eastern subdistrict, and some portion of the west. Eventually, Karatsu city became its own administrative district, in modern Saga prefecture, and so did Hirado city, in what was the old Northern Matsura sub-district, joining Nagasaki prefecture. The western sub-district went to Karatsu or incorporated as Imari, known for their Imari-ware pottery. And that left a small portion of the northern sub-district.

The incorporated villages and islands eventually came together as Matsuura city, in Nagasaki prefecture, which is what you’ll see, today. And that is why, looking at a modern map, “Matsura” and modern “Matsuura” are not precisely in the same place.

That history also helps demonstrate the historical connections between Karatsu, Hirado, Iki, and Tsushima—as well as the Goto islands. This region was where the Matsura clan arose, which controlled at least out to Iki, Hirado, and the Goto archipelago, and it was known for its strong navy, among other things.

For our trip, heading to Karatsu was originally borne out of convenience: Our goal was to take the ferry so that we could travel along the ocean routes. We had traveled the route from Izuhara, on Tsushima, to Ashibe port, on Iki island. During that trip it was interesting to watch as Tsushima disappeared and then eventually Iki appeared on the horizon, but it wasn’t immediate, and I suspect you would have wanted an experienced crew who knew the route and knew what to look for. Conversely, from Indoji port, on Iki, to Karatsu I felt like we were constantly in sight of one island or another, or at least could see the mountains of Kyushu to get our bearings. There wasn’t really a time that felt like we were that far out from land. Even so, it would still have been a treacherous crossing back in the day.

Coming in to Karatsu from the ferry, the first thing you will notice is the castle. Karatsu castle, also known as Maizuru Castle, is a reconstructed castle, but it really does provide a clear view of what one would have seen. The original was abandoned in the Meiji period and sold off in 1871. The main keep was later demolished and made into a park. In 1966 they built a new, 5-storey keep on the original base, and from 1989 onward have continued to make improvements to various parts of the castle moats and walls. You can still see the layout of the Ninomaru and honmaru sections of the castle, encompassing the old samurai districts of the jokamachi, or castle town, of Karatsu during the Edo period.

Our primary goal in Karatsu, however, was not castle focused. We wanted to go back to an earlier time – the Yayoi period, to be precise - and Karatsu and the Matsuro-kan did not disappoint. While not quite as extensive as the reconstruction at other Yayoi sites like Harunotsuji or Yoshinogari, the site at the Matsuro-kan is still impressive in its own right.

What is the Matsuro-kan, you might ask? It is the building and grounds of what is also known as the Nabatake site. In 1980, construction workers were excavating for a road through the Nabatake section of Karatsu when they noticed they were pulling up artifacts. An investigation between 1980 to 1981 determined that the artifacts were from the late Jomon to middle Yayoi period. Further investigation discovered the presence of old rice paddies. In 1983 the site was designated as a national historic site, further excavations were carried out, and the Matsurokan was built to house the artifacts and also provide some reconstructions of what the rice paddies would have looked like. For context these are some of the oldest rice paddies found in Japan, along with the nearby Itazuke rice paddies, in neighboring Fukuoka prefecture, and are key for giving us insights into what we know about early rice field cultivation.

Here I should point out that these fields were in use through the middle Yayoi period, while the mission to Yamato—or Yamatai—recorded in the Weizhi would have been in the late Yayoi or early Kofun period, so likely several hundred years later. There are other Yayoi settlement remains found up and around the peninsula, and there are Kofun in the area, especially along the banks of the Matsura river. Given how built up much of the area is, it is possible that any large scale settlement may have been destroyed by subsequent settlements, or is somewhere that there just hasn’t been a good reason for a full excavation. Still, who knows what we might eventually find.

The Matsurokan appears to stick with the dating of the Yayoi period from about 300 BCE. This is based largely on assumptions regarding the development of different pottery styles. Recent research has suggested that this should be pushed back to about 800 or even 1000 BCE, suggesting a more gradual development. For our purposes, it is enough to note that this site appears to cover from the final Jomon era in Kyushu to the coming of wet rice agriculture with the advancing Yayoi culture.

Based on what was found at the site, the wet rice paddies were created in what at least one scholar has suggested as a “primitive” wet rice paddy. The paddies themselves appear to have been placed in a naturally swampy area, irrigated by a natural stream. This would have made flooding the fields relatively simple, without the large ponds or waterworks required to cover a more extensive area. This may have sufficed for a small village, possibly only a handful of families living together and working the land.

Besides the impressions of the paddies themselves, various tools, pottery, and more were also found at the site. Stone harvesting knives were plentiful—a semicircular stone knife that was held in the fingers of one hand, allowing a harvester to grasp the stalks and cut them quickly. This was the standard method of harvesting prior to the arrival of the sickle, or kama, and is still in use in some parts of China and Southeast Asia. It is more labor intensive than the sickle, but provides some benefits in the consistency and lack of waste product.

The Matsurokan demonstrates how a lot of the Yayoi tools are, in fact, still in use in one form or another in different cultures that also absorbed rice cultivation, showing how widespread it became.

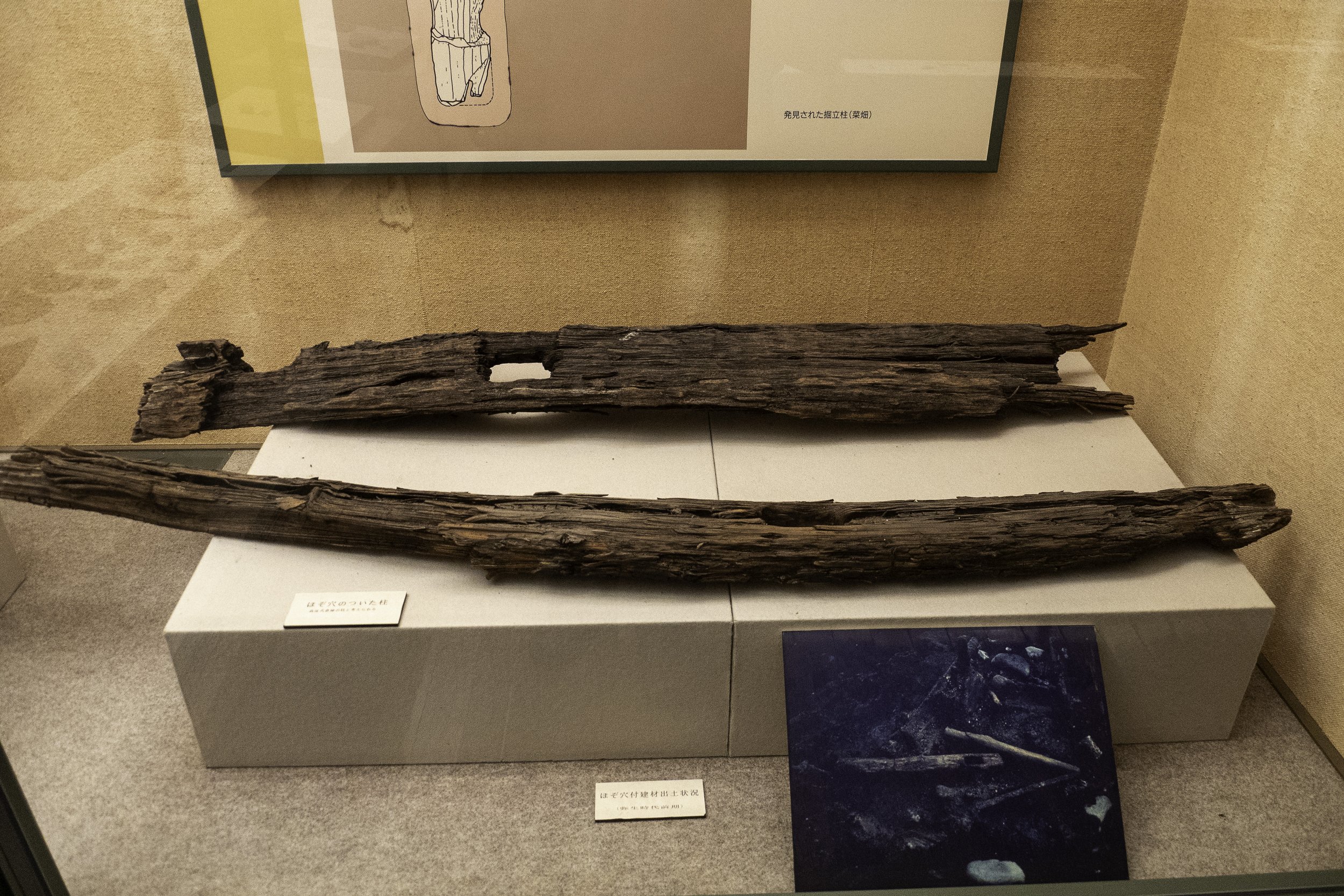

In addition, there are artifacts such as shards of pottery showing what looks to be the imprint of a woven fabric, and various equipment for weaving and sewing. We have some beams and posts from buildings, which give us something at least try to guess at how things were put together.

There are bones of various animals as well as stone arrowheads. There are also fish and even dugong bones, suggesting they also made a living from the nearby sea. And there are various bits of jewelry, including magatama, and what appears to be a shark’s tooth with holes drilled in so it could be worn on a cord.

There are also carbonized rice grains found at the site, likely grown there.

We don’t have any ancient strains of rice that can be proven to come from these fields, but in their reconstruction, outside the museum, they have rebuilt some of the rice fields and grow old rice variants in them. This is used, in part, to teach local schoolchildren about rice cultivation – in fact, local schools are allocated individual paddies each growing season.

Besides the rice paddies, the Matsurokan also boasts several reconstructed dwellings. These are similar to ones you might find elsewhere depicting what life was like back in the Yayoi period.

As the Yayoi period gave way to the kofun, we do see some mounded tombs in the area, though not quite as many as in others. Matsura appears to be rather rural.

Around the Heian period, we see the rise of a local group that comes to be known as the Matsura group, or Matsura-tou, which eventually consolidated into the Matsura family. There are several lineages claiming that the Matsura family descended from the Minamoto or Abe clans or through branch families thereof. Matsura-to itself is sometimes called the 48 factions of Matsura. It wasn’t as much a family as an alliance of local warriors, each with their own base of operations. I can’t quite tell if the lineage of the later Matsura clan, as they were known, were meant to represent a single lineage or the various lineages that came together. For all we know, they may have married into official families or otherwise concocted lineages to help legitimize them as much as anything else—this far out from the center, in the 11th century, there wasn’t necessarily as much oversight.

Early in the 11th century they also had a chance to prove themselves with the Toi invasion – that was the Jurchen invasion we mentioned last couple episodes. After the Toi invaders attacked Tsushima and Iki, they set their sites on Hakata Bay, which was the closest landing to the Dazaifu, the Yamato government in Kyushu. They were chased off and headed down the coast. Minamoto Tomo is said to have led the forces that repelled the Toi invaders, who finally departed altogether, striking one more time on Tsushima before heading back to wherever they came from.

Minamoto Tomo is said, at least in some stories, to have been the founder of the Matsura clan, or at least the leader of the 48 factions, which then coalesced into the Matsura clan, which eventually would run the Hirado domain.

Over two hundred and fifty years after the Toi Invasion would come the Mongols. If the Toi were bad, the Mongols were much worse. The Toi were a band of marauders, who caused a lot of havoc, but do not appear to have had state backing. The Mongols were perhaps more appropriately the Yuan empire, who had already conquered the Yellow river valley and were working on the Song dynasty along the Yangzi. While the Toi had brought with them Goryeo warriors as well—who may or may not have joined up willingly—the Mongols had huge armies from all over that they could throw at a problem.

As we talked about in the past two episodes, the Mongols swept through Tsushima and Iki and then headed straight for Hakata, the closest landing zone to the Dazaifu, the government outpost in Kyushu. Even during the height of the Kamakura shogunate, this was still an important administrative center, and would have given the Mongols a huge advantage on holding territory and eventually sweeping up the archipelago.

Fortunately, they were stopped. Whether it was the gumption, skill, and downright stubbornness of their samurai foes or the divine wind that swept up from the ocean, the Mongols were turned back, twice.

During each of these invasions, the Matsura clan and others rushed to the defense of the nation, but unlike with the Toi invasions, there do not appear to have been any serious battles along the Matsuura coastline—not that I can make out, anyway.

After the Mongol invasion, Kyushu was not left out of the troubles that would follow, including the downfall of the Hojo, the rise of the Ashikaga, and the eventual breakdown of the shogunal system into the period known as the Warring States period. Through it all the Matsura continued to ply the seas and encourage the trade from which they and others, like the Sou of Tsushima, came to depend on. They also allied with other entrepreneurial seafarers, known to others as pirates, and they started trading with a group of weird looking people with hairy beards and pale skin, who came to be known as the Nanban, the southern barbarians—known to us, primarily, as the Portuguese.

One faction of the Matsura were the Hata—no relation to the Hata that set up in what would become the Kyoto region in the early periods of Yamato state formation. The Hata ruled the area that would become Karatsu, but eventually they were taken over by the Ryuzoji, who were allied with Toyotomi Hideyoshi.

Hideyoshi’s interest in the Karatsu and Matsura area had to do with its easy access to the continent. And so Hideyoshi began to pay attention to Nagoya, at the end of the peninsula down from Karatsu.

And no, not that Nagoya. If you hear Nagoya, today, you are probably talking about the bustling metropolis in Aichi, which was where Toyotomi himself got his start, growing up and going to work for the local warlord, named Oda Nobunaga. Due to a quirk of Japanese names and how they read particular characters, this is a different Nagoya.

The Kyushu Nagoya had been one of the Matsura trading posts, run by a sub-branch of the Hata family, who had built a castle on the site. Hideyoshi had much grander plans for the area. In 1591 he began work on a massive castle and associated castle town. This castle was to be his new headquarters, and he moved his entire retinue there from Osaka, with an expectation that all of the daimyo would follow him. Sure enough, they showed up with their own vassals, setting up camps around the peninsula and in the new city-to-be.

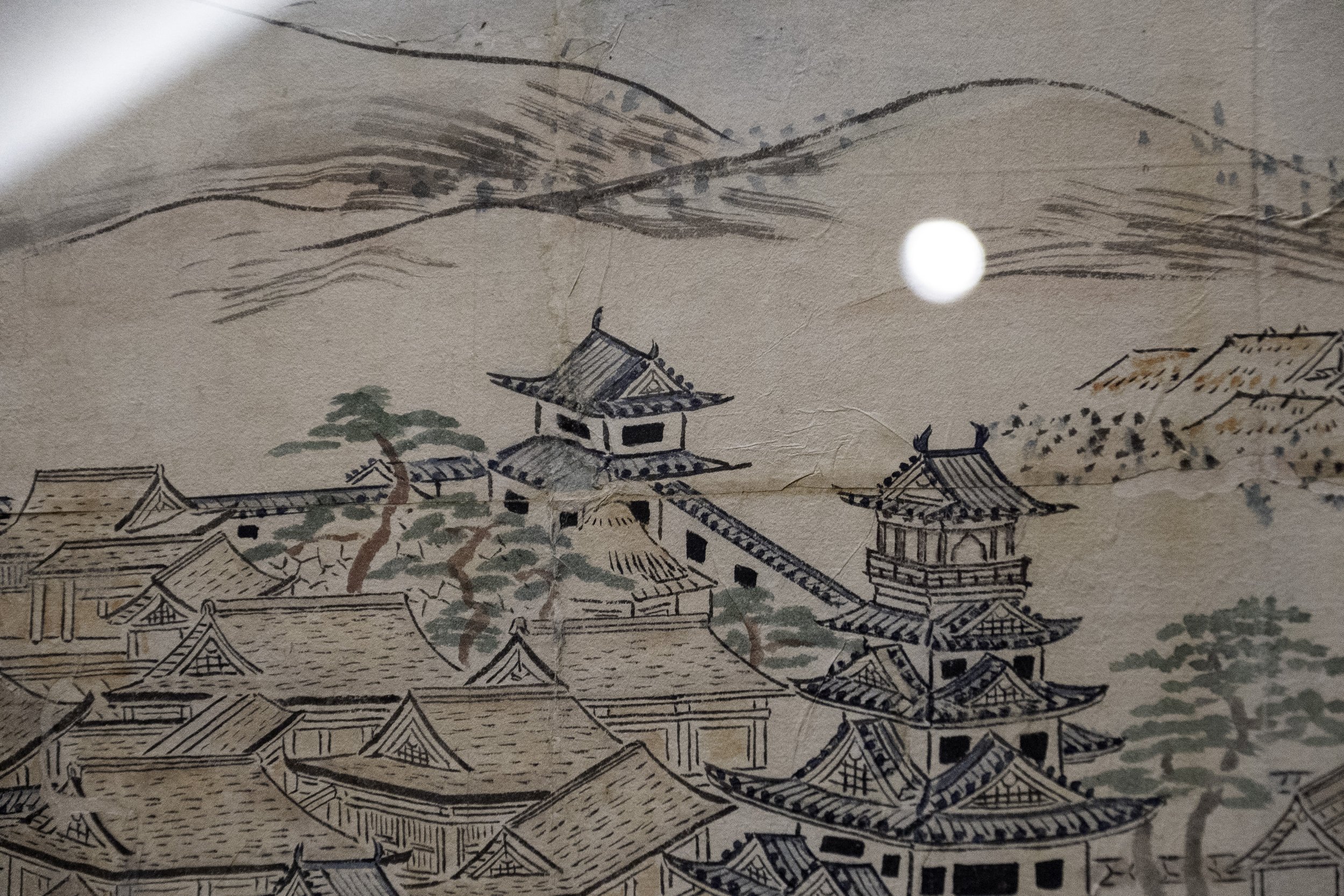

The castle was the base of operations from which Hideyoshi coordinated the invasions of Korea. It was a massive undertaking, and extremely impressive. The city itself sprung up, and although the wood was still new, and the buildings somewhat hastily put together, it was soon a bustling metropolis and briefly became the center of art and culture in the entire archipelago.

Hideyoshi himself had a teahouse built within the confines of the castle, where he apparently spent most of his days, even when receiving reports on how things were going across the sea on the archipelago. The city had a Noh theater, as well. It must have been a sight to see.

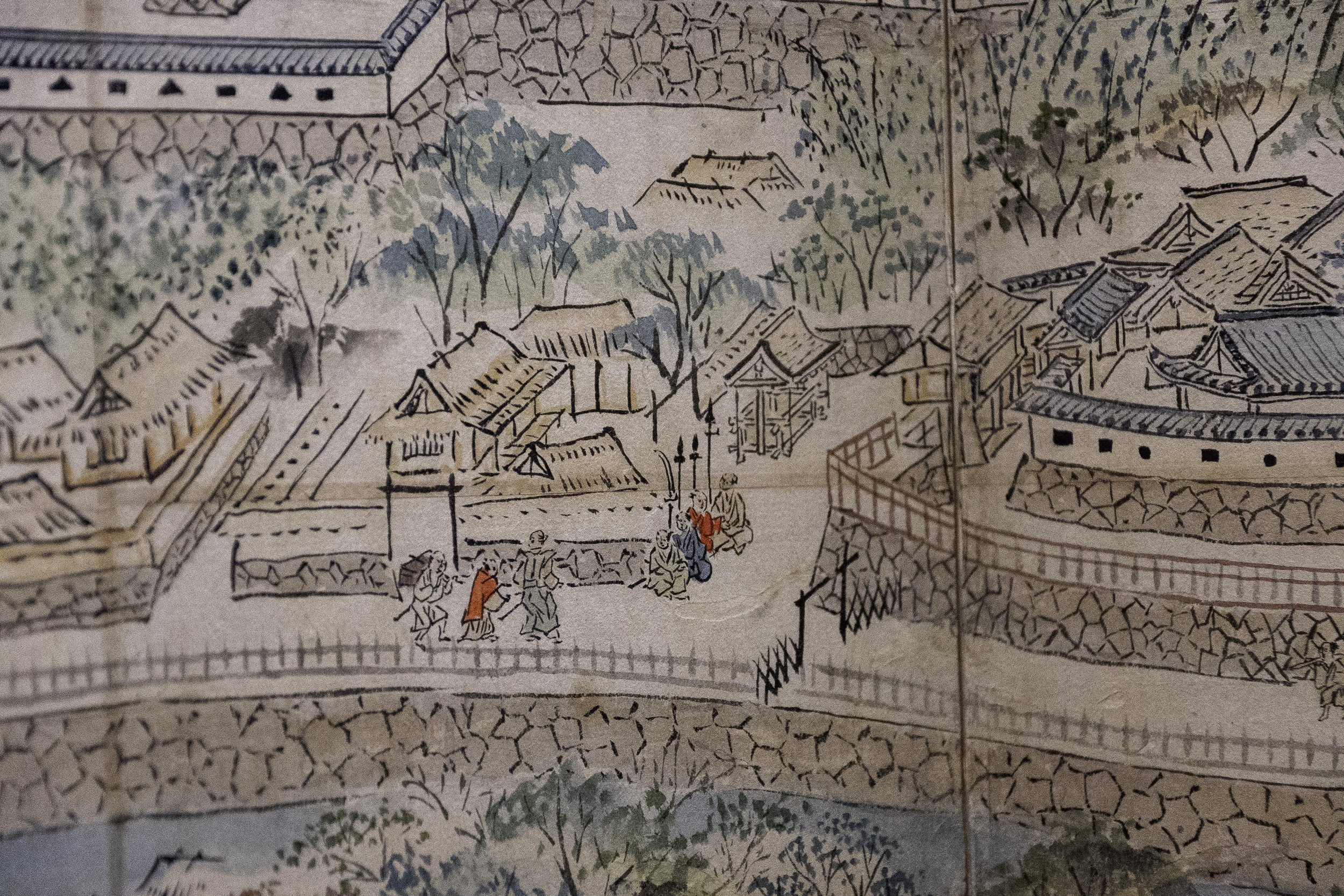

As for the castle itself, based on the remains, it was massive. It appears to use the contours of the hill upon which it sits. It seems there was a previous castle there of some kind, and it is unclear how much this was merely expanded, but Hideyoshi’s new castle was truly monumental, with a labyrinth of gates to get in -- similar to Himeji Castle, for anyone who has been there, but with a serious vertical incline as well. Nagoya Castle was second only to Osaka castle, and yet it was erected quickly—only 8 months. I guess that’s what you can do when you can mobilize all of the daimyo across Japan. Even today, ruined as it is, the walls tower over you, and you can spend hours wandering the grounds.

For all that it was impressive, the good times at Nagoya Castle lasted only for a brief seven years—when Hideyoshi passed away, the council of regents moved back to Osaka, and Nagoya castle was deliberately destroyed, stones removed from the walls such that it could never survive a true siege. This was a sign to the Korean peninsula – the Joseon court - that, with the death of the taiko, Japan had given up any pretext of conquering the peninsula.

Today, only the stones and earthworks remain of the briefly thriving city, but on the grounds is a wonderful museum that catalogs this particular slice of Medieval life. The Nagoya Castle Museum of Saga prefecture is off the beaten path—there is no train, so you’ll need to take a bus or private car to get there—but it is well worth it.

The museum itself is dedicated to Japanese and Korean cross-strait relations, which feels a bit like atonement given that the castle was built with conquest in mind.

Of course, the centerpiece of the Museum is the castle, but it also does a good job telling the story of relations between the peninsula and the archipelago. It starts in the ancient times, talking about how, even during the Jomon period, there were commonalities in fishhooks and similar equipment found from Kyushu up through the Korean peninsula. From there, of course, trade continued, as we’ve seen in our journey through the Chronicles. It talks about some of the shared cultural items found from the Yayoi through the Kofun, and also demonstrates how some of the earliest Buddhist statues have clear similarities to those found in Silla. It goes over the various missions back and forth, and even gives a map of the Toi Invasion that we talked about hitting Tsushima and Iki.

The Mongol invasion is also heavily talked about, but not nearly so much as the invasion of Korea. There is another reproduction of the letter of King Sejeong, with the faked seal from the Sou clan in Tsushima. This of course, was the period when they built Nagoya-jo into a castle and city of at least 100,000 people, almost overnight. Even the Nanban were there, trading in the city while supplies from across the country were gathered and shipped off to keep troops fed on the invasion of Korea.

There are plenty of images from this time—from a Ming envoy to Nagoya castle to images of the invasion from the Korean perspective, with Koreanized samurai manning the walls of the castles they had taken. They don’t exactly lionize the samurai, but they don’t accentuate some of the more horrific things, either, like the piles of ears taken from those killed because taking their heads, as was standard practice in older days, was too cumbersome.

There is also some discussion of relations afterwards—of the Joseon embassies, though those went through Hakata, Nagoya-jo having long been abandoned at that point. For reasons one can probably understand, it doesn’t go into the post-Edo relations, as that is much more modern history.

After the destruction of Nagoya castle, the area was largely abandoned, but the city of Karatsu proper really thrived during the Edo period. Karatsu was also a castle town, as we’ve mentioned, but a bit out of the way. As sailing ships were now more sturdy and able to handle longer sea crossings, it was now often Hakata, in Fukuoka, that received much of the trade, and the Dutch traders who had replaced the Portuguese, were limited to Dejima, in Nagasaki.

When Hideyoshi swept through, the Hata were not exactly considered trustworthy, and were placed under the Nabeshima, a branch of their rivals, the Ryuzouji. During the invasion of Korea, the Hata rebelled, and were destroyed for it in 1593. Their territory was given to Terazawa Hirotaka, who had been put in charge of the construction of Nagoya castle and later put in charge of the logistics for the invasion effort from the Kyushu side. As a result, he was granted the lands formerly controlled by the Hata, including Karatsu, and what would become the Karatsu domain.

Hirotaka could see which way the wind blew—in more ways than one. After Hideyoshi’s death, he supported Tokugawa Ieyasu, allowing him to keep and even expand his fief. He redirected the Matsura river—then known as the Hata river—to its present course, and he built a pine grove along the northern beach that is the third largest such grove in all of Japan. Known as the “Niji no Matsubara”, or the ”Rainbow Pine Forest” for its shape, it was erected as a windbreak to protect the precious farmland just on the other side. It is still there today, still managed, and quite famous. You can drive through the pine trees or stop and walk through them, even out to the beach. And there is even a fantastic burger truck that parks along the main road through the pine grove, so you can enjoy a lovely picnic among the trees.

The Terazawa would not remain in place for very long. During the Shimabara rebellion of the early 17th century—a rebellion based on either taxes or Christianity, depending on whom you ask—the Terazawa line was extinguished. Terazawa Katataka, then ruler of the Karatsu domain, was held liable for mismanagement of the domain and loss of a castle to the rebels. He had land confiscated and he felt publicly humiliated, and so he took his own life while he was in Edo. As he had no heir, the Terazawa line died out.

Karatsu domain went through a variety of hands after that. Its value fluctuated, but it is generally thought that the real value of the domain, thanks to the ability to trade, was well beyond what it was assessed to produce. As such it was a lucrative position, and also held sway as a check against Nagasaki, watching the trade there with the Dutch merchants. Because of all of this, the lord of Karatsu was also banned from holding certain government positions, so as not to distract from their duties, making the position something of a blessing and a curse.

Through the years, Karatsu thrived. They were and are still known for a type of traditional pottery, known as Karatsumono, or Karatsuware, and they maintain elaborate festivals.

One of the festivals, the Karatsu Kunchi, is considered a UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage.The Karatsu Kunchi is an annual parade where neighborhood associations carry giant floats through the city from Karatsu Shrine down to the shore. It was inspired, in the early 19th century, by the famous Gion Matsuri of Kyoto—a wealthy merchant saw that and donated the first lion-head float to Karatsu Shrine. Later, others would create their own floats.

These floats, known as “Hikiyama” or “pulled mountains” can be five or six meters high and weigh anywhere from two to five tons. There appear to be 14 hikiyama, currently, though there used to be 15—a black lion is currently missing. The floats have gone through a few iterations, but are largely the same, and often have some relationship to the neighborhoods sponsoring them.

From Matsura, aka Matsuro-koku, we went north along the coast of Kyushu to Itoshima, thought to the be old country of Ito-koku, and beyond that, the Na-koku of Fukuoka. We’ll cover both of those in our next and final installment of our Gishiwajinden tour.

If you like what we are doing, tell your friends and feel free to rate us wherever you listen to podcasts. If you feel the need to do more, and want to help us keep this going, we have information about how you can donate on Patreon or through our KoFi site, ko-fi.com/sengokudaimyo, or find the links over at our main website, SengokuDaimyo.com/Podcast, where we will have some more discussion on topics from this episode.

Also, feel free to reach out to us at our Sengoku Daimyo Facebook page. You can also email us at the.sengoku.daimyo@gmail.com.

Thank you, also, to Ellen for their work editing the podcast.

And that’s all for now. Thank you again, and I’ll see you next episode on Sengoku Daimyo’s Chronicles of Japan.

References

Conlan, Thomas. (2001). In little need of divine intervention : Takezaki Suenaga's scrolls of the Mongol invasions of Japan. Ithaca, N.Y. :East Asia Program, Cornell University,

Aston, W. G. (1972). Nihongi, chronicles of Japan from the earliest times to A.D. 697. London: Allen & Unwin. ISBN0-80480984-4