Previous Episodes

- February 2026

- January 2026

- December 2025

- November 2025

- October 2025

- September 2025

- August 2025

- July 2025

- June 2025

- May 2025

- April 2025

- March 2025

- February 2025

- January 2025

- December 2024

- November 2024

- October 2024

- September 2024

- August 2024

- July 2024

- June 2024

- May 2024

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

This episode we covered the final leg of our trip to Ito and Na—which is to say Itoshima and Fukuoka. There are a few photos, below, and the famous mirror at the start of this post.

-

Welcome to Sengoku Daimyo’s Chronicles of Japan. My name is Joshua, and this is Gishiwajinden Part Five: Ito-koku and Na-koku

This episode we are finishing up our Gishiwajinden Tour, focusing on our journey to Ito-koku and Na-koku, or modern day Itoshima and Fukuoka. We’ll talk about what we know from the records of these two areas in the Yayoi and early Kofun periods, and then look at some of the later history, with the development of the Dazaifu, the build up of Hakata and Fukuoka, and more. A key thread through all of this will be our discussion about why it was Yamato, and not these early states, who eventually became paramount. If this is where things like wet paddy rice agriculture started, and they had such close ties to the continent, including sending a mission to the Han dynasty, why did the political center shift over to Yamato, instead? It is certainly something to wonder about, and without anything written down by the elites of Na and Ito we can only really guess based on what we see in the histories and the archaeological record.

We ended our tour in Na for a reason: while the Gishiwajinden—the Japanese section of the Wei Chronicles—describes the trip from the continent all the way to Yamatai, the locations beyond Na are largely conjecture. Did ancient travelers continue from Na along the Japan Sea coast up to Izumo and then travel down somewhere between Izumo and Tsuruga to the Nara Basin? Or did they travel the Inland Sea Route, with its calmer waters but greater susceptibility to pirates that could hide amongst the various islands and coves? Or was Yamatai on the island of Kyushu, and perhaps the name just happens to sound similar to the Yamato of Nara?

Unfortunately, the Wei Chronicles have more than a few problems with accuracy, including problems with directions, meaning that at most we have some confidence in the locations out to “Na”, but beyond that it gets more complicated. And even “Na” has some questions, but we’ll get to that later.

Unlike the other points on our journey, we didn’t stay overnight at “Ito-koku”, , and we only briefly stayed at Na—modern Fukuoka, but I’ll still try to give an account of what was going on in both places, and drawing on some past visits to the area to fill in the gaps for you.

Both the Na and Ito sites are believed to be in the modern Fukuoka prefecture, in Itoshima and Fukuoka cities. Fukuoka prefecture itself actually spans all the way up to the Shimonoseki straits and includes the old territory of Tsukushi—Chikuzen and Chikugo—as well as the westernmost part of Buzen, the “closer” part of the old land of “Toyo” on the Seto Inland Sea side of Kyushu.

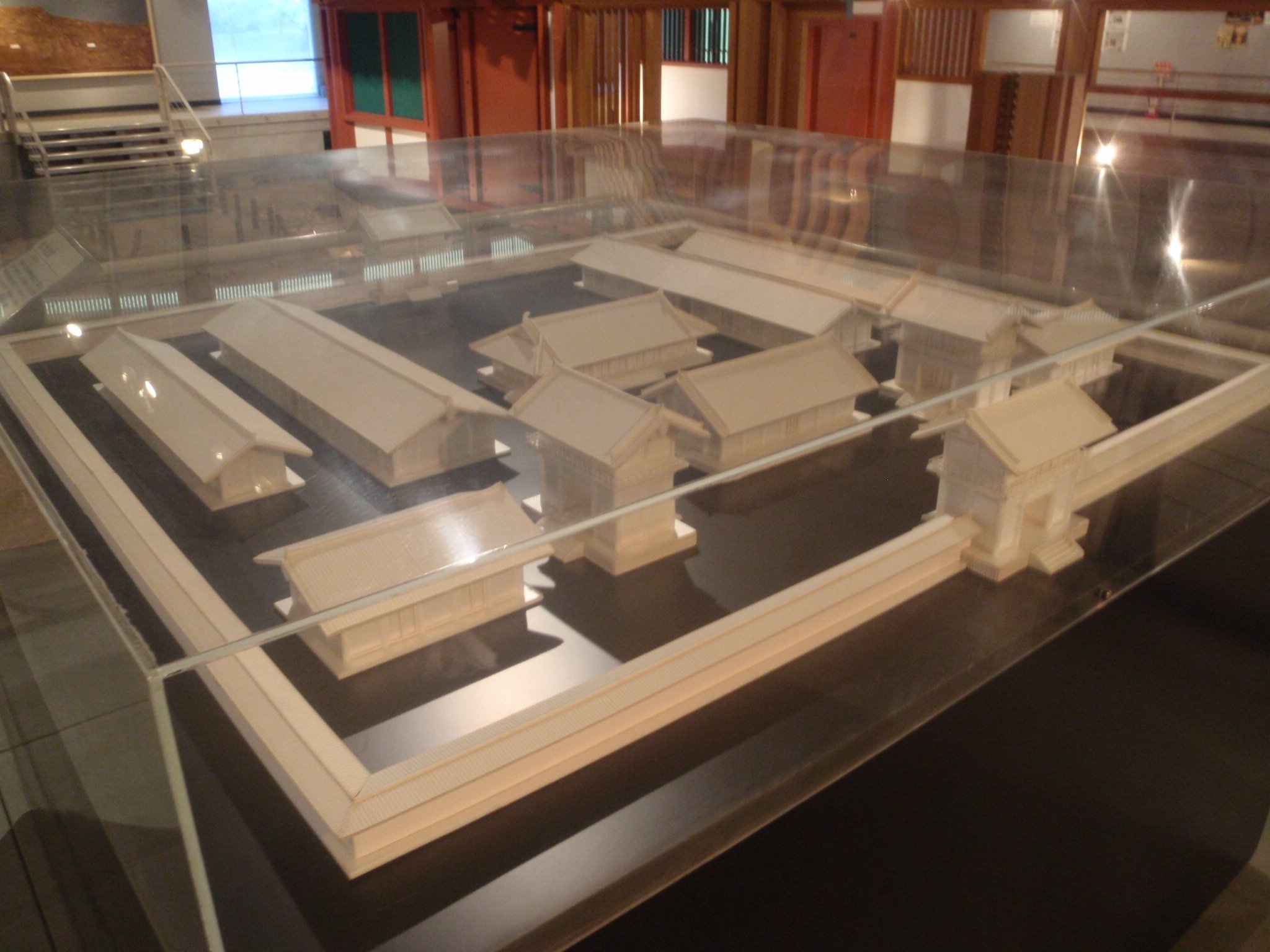

When it comes to locating the country of Ito-koku, we have lots of clues from current place names. The modern Itoshima peninsula, which, in old records, was known as the country of Ito, and was later divided into the districts of Ito and Shima. Shima district, at the end of the peninsula, may have once been an island—or nearly so. It is thought that there was a waterway between the two areas, stretching from Funakoshi bay in the south to Imazu Bay, in the north, in Fukuoka proper. Over time this area was filled in with deposits from the local rivers, making it perfect for the Yayoi style wet rice paddy agriculture that was the hallmark of the growth in that period. And indeed there are certainly plenty of Yayoi and Kofun era ruins in the area, especially in eastern reaches of the modern city of Itoshima, which reside in the valley that backs up to Mt. Raizan. There you can find the Ito-koku History Museum, which tells much of the story of Ito.

The Weizhi, or the Wei Chronicles, note that Ito-koku had roughly a thousand households, with various officials under their own Queen, making it one of the few Wa countries that the Chroniclers specifically noted as being a “kingdom”, though still under the nominal hegemony of the queen of Yamatai or Yamateg.

If you continue eastward along the coast from Itoshima, you next hit Nishi-ku, the Western Ward, of modern Fukuoka city, which now continues to sprawl around Hakata Bay. Nishi-ku itself used to also be known as “Ito”, though spelled slightly differently, and you can still find Ito Shrine in the area. So was this part of Ito-koku also? It’s very possible.

Na-koku, or the country of Na, was probably on the eastern edge of modern Fukuoka, perhaps around the area known as Hakata down to modern Kasuga. Much like in Karatsu, this area features some of the earliest rice fields ever found in Japan – in this case, in the Itazuke neighborhood, just south of Fukuoka airport. The land here is mostly flat, alluvial plains, formed by the rivers that empty out into Hakata Bay, another great area for early rice agriculture.

Locating the country of Na is interesting for several reasons. For one, unlike all of the other Wei Chronicles sites we’ve mentioned, there is no clear surviving placename that obviously matches up between “Na” and the local area. It is a short enough name that it may simply be difficult to distinguish which “Na” is meant, though there is a “Naka” district in Kasuga that may show some promise. There certainly is evidence for a sizeable settlement, but that’s much more tenuous than the placenames for other areas, which remained largely in use in some form up to the modern day, it would seem.

The name “Na” shows up in more than just the Weizhi, and it is also mentiond in the Houhan-shu, or the Record of the Later Han, a work compiled later than the Weizhi, but using older records from the Late Han dynasty period. There it is asserted that the country of Na was one of the 99 some-odd countries of Wa, and they sent an embassy to the Later Han court, where they received a gold seal made out to the “King of Na of Wa”.

We talked about this in Episode 10: The Islands of the Immortals: That seal, made of gold, was seemingly found in the Edo period—1784, to be precise. A farmer claimed to have found it on Shika island, in Hakata Bay, which is quite prominent, and connected to the mainland with a periodically-submerged causeway. The description of the find—in a box made up of stones, with a large stone on top that required at least two men to move it—seems like it could have been an old burial of some kind. The island certainly makes sense as an elite burial site, overlooking Hakata Bay, which was likely an important feature of the lifeways of the community.

While there have been questions about the authenticity of the seal, if it is a forgery, it is quite well done. It looks similar to other Han era seals, and we don’t really have a way to date the gold it is made of. Without the actual context we can’t be quite sure.

This certainly seems like pretty strong evidence of the country of Na in this area, somewhere – probably not on the island itself, then close by.So unless something else comes along, I think we can say that this is at least the vicinity of the old country of Na.

Okay, so now that we’ve talked in general about where these two places were, let’s go back and look at them in more detail.

The Ito-koku site is just up the coast from where we stayed for Matsuro-koku, in Karatsu, which all makes sense from the position of the Chronicles in that it says the early envoys traveled overland from one place to the other. Of course it also says they traveled southeast, which is not correct as the route is actually northeast. However, they had traveled southeast from the Korean peninsula to Tsushima and then Iki and Matsuro, so that direction was well established, and this is an easy enough error that could have been made by the actual envoys or by later scribes, as it would be a one character difference.

For Ito-koku, as with Matsuro-koku, we have no large, reconstructed sites similar to Harunotsuji on Iki or Yoshinogari, further inland in Saga prefecture, where we have an entire, large, so-called “kingly” settlement. There is evidence of settlements, though, both near the major burial sites as well as around the peninsula. And as for those burial sites, well, Ito has a few, and they aren’t merely important because of their size. Size is often an indication of the amount of labor that a leader must have been able to mobilize, and so it can be used to get a general sense of the power that a given leader or system was able to wield, as they could presumably turn that labor to other users as well. However, it is also important to look at other factors, like burial goods. What kind of elite material was the community giving up and placing with the deceased?

That is the case with the first site we’ll discuss, the Hirabaru burial mound. At first glance it isn’t much—a relatively unassuming square mound, about 12 by 14 meters, and less than 2 meters in height. It was discovered in 1965 by a farmer who started digging a trench to plant an orchard and started pulling up broken pieces of a bronze mirror, one of the first clues that this was someone important. They later found various post holes around the site, suggesting that it was more than just an earthen mound, and as they excavated the site they found pottery, beads, mirrors, and more.

Let’s start with those post-holes. It looks like there was at least one large pillar set up due east of the burial. We don’t know how tall it was, but it was likely of some height given the size of the pillar hole—I’ve seen some estimates that it could have been up to 70 meters tall. A tall pole would have provided visibility, and it may also be significant that it was east, in the direction of the rising sun. We know that the ancient Wa had a particular connection with the sun, and this may be further evidence of that. There are other holes that may be a gate, and possible a storehouse nearby, presumably for various ritual items, etc. Suddenly, even without knowing exactly what was there, we start to see a picture of a large, manmade complex that seems to be centered on this burial and whomever is there.

On top of that, there was a mirror in the tomb that was larger than any other ever found in Japan at that time—certainly the largest round mirror of that period. It is not one of the triangular rimmed mirrors that Yamato is known for, but may have been part of another large cache brought over from the mainland. About 40 mirrors in total, many of them very large, were found buried in the tomb, some of which appear to have been broken for some reason. Furthermore, the large mirrors appear to fit within the dimensions given the Great Mirror—the Yata no kagami—housed at the sacred Ise Shrine. There is a document in 804, the “Koutai Jingu Gishiki Chou”, detailing the rituals of Ise shrine, which describes the sacred mirror sitting in a box with an inner diameter of 1 shaku, 6 sun, and 3 bu, or approximately 49.4 centimeters, at least using modern conversions. The same measurements are given in the 10th century Engi Shiki. So we can assume that the mirror in Ise, which nobody is allowed to actually see, let alone measure, is smaller than that, but not by much, as the box would have been made to fit the mirror, specifically. It isn’t like you can just grab a box from Mirror Depot. The mirrors found at Hirabaru Mound measure 46.5 centimeters, and have a floral pattern with an eight petaled flower on the back. Could this mirror be from the same mold or the same cache, at least, as the sacred mirror at Ise? At the very least, they would seem to be of comparable value.

In addition, there were many beads, jars, etc. Noticeably absent from the burial were swords and weapons. Based on this, some have argued that this was the burial of a queen of Ito-koku. There is evidence that this may be the case, but I don’t think the presence of weapons, or the lack thereof, is necessarily a good indicator. After all, we see in the old stories that women were also found wielding swords and leading troops into battle. So it’s dangerous to make assumptions about gender based on this aspect alone.

I wonder if the Hirabaru tomb assemblage might have more to do with something else we see in Yamato and which was likely applicable elsewhere in the archipelago: a system of co-rulership, where one role might have to do more with administrative and/or ritual practice, regardless of gender. This burial assemblage or mirrors and other non-weapons might reflect this kind of position. The Weizhi often mentions “secondary” or “assistant” positions, which may have truly been subordinate to a primary ruler, or could have just been misunderstood by the Wei envoys, who saw everything through their particular cultural stratification. In a similar fashion, early European explorers would often name people “king”—from the daimyo of Sengoku era Japan to Wahunsenacawh, known popularly as “Powhatan” for the name of his people, on what would become known as North America. That isn’t to say that these weren’t powerful individuals, but the term “king” comes with a lot of Eurocentric assumptions and ideas about power, stratification, etc. Is there any reason to believe that the Wei envoys and later chroniclers were necessarily better at describing other cultures?

And of course we don’t have any physical remains of the actual individual buried there, either. However, there is a good reason to suggest that this may have been a female ruler, and that is because of something in the Weizhi, which specifically says that the people of Ito lived under the rule of a female king, aka a queen, using a description not unlike what is used for Queen Himiko. In fact, Ito gets some special treatment in the record, even though it isn’t the largest of the countries. Let’s look at those numbers first: Tsushima is said to have 1,000 households, while Iki is more like 3,000. Matsuro is then counted at 4,000 families, but Ito is only said to have 1,000, similar to Tsushima. Just over the mountains and along the Bay, the country of Na is then counted at a whopping 20,000 households, so 20 times as many. These numbers are probably not entirely accurate, but do give an impression of scale, at least.

But what distinguishes Ito-koku in this is that we are told that it had a special place for envoys from the Korean peninsula to rest when they came. It makes you wonder about this little place called Ito.

Hirabaru is not the only kingly tomb in the area. Walk about 20 to 30 minutes further into the valley, and you might just find a couple of other burials—in particular Mikumo-Minami Shouji, discovered in 1822, and Iwara-Yarimizo, which includes artifacts discovered in the 1780s in the area between Mikumo and Iwara as they were digging a trench. Based on evidence and descriptions, we know that they pulled out more bronze mirrors and other elite goods indicative of the late Yayoi paramounts. In these areas they have also found a number of post holes suggesting other buildings—enough to perhaps have a relatively large settlement. As noted earlier, we do not have a reconstructed village like in Harunotsuji or Yoshinogari, given that these are private fields, so the shape of the ancient landscape isn’t as immediately impressive to people looking at the area, today.

The apparent dwellings are largely found in the triangle created between two rivers, which would have been the water source for local rice paddies. The tombs and burials are found mostly on the outskirts, with the exception of the kingly burial of Mikumo-Minami Shouji. This is also interesting when you consider that the later Hirabaru mound was situated some distance away, raising a bunch of questions that we frankly do not have answers for.

The area of these ruins is not small. It covers roughly 40.5 hectares, one of the largest Yayoi settlements so far discovered. Of course, traces of other large settlements—like something in the Fukuoka area or back in Yamato—may have been destroyed by later construction, particularly in heavily developed areas. This is interesting, though, when you consider that the Weizhi only claimed some 1,000 households.

There are also other graves, such as various dolmens, across Ito and Shima, similar to those found on the peninsula, and plenty of other burials across both ancient districts. And as the Yayoi culture shifted, influence of Yamato can be seen. While Ito-koku clearly had their own burial practices, which were similar to, but not exactly like, those in the rest of the archipelago, we can see them start to adopt the keyhole style tomb mounds popular in Yamato.

During the kofun period, the area of Itoshima built at least 60 identified keyhole shaped tombs, with a remarkable number of them from the early kofun period. Among these is Ikisan-Choushizuka Kofun, a large, round keyhole tomb mound with a vertical stone pit burial, estimated to have been built in the latter half of the 4th century. At 103 meters in length, it is the largest round keyhole tomb on the Genkai coast—that is to say the northwest coast of Kyushu.

All of these very Yamato-style tombs would appear to indicate a particular connection between Ito and Yamato—though what, exactly, that looked like is still up for debate. According to the various early Chronicles, of course, this would be explained because, from an early period, Yamato is said to have expanded their state to Kyushu and then even on to the Korean peninsula. In particular, the Chronicles talk about “Tsukushi”, which is both used as shorthand for the entirety of Kyushu, while also indicating the area largely encompassing modern Fukuoka prefecture. On the other hand, this may have been a sign of Ito demonstrating its own independence and its own prestige by emulating Yamato and showing that they, too, could build these large keyhole tombs. After all, the round keyhole shape is generally thought to have been reserved, in Yamato, for members of the royal family, and Ito-koku may have been using it similarly for their own royal leaders.

It may even be something in between—Ito-koku may have recognized Yamato’s influence and leadership, but more in the breach than in actuality. Afterall, until the standup of things like the various Miyake and the Dazai, we aren’t aware of a direct outpost of the Yamato government on Kyushu. The Miyake, you may recall, were the ”royal granaries”, which were basically administrative regions overseeing rice land that was directly controlled by Yamato, while the Dazai was the Yamato government outpost in Kyushu for handling continental affairs. On top of a lack of local control in the early Kofun, the Weizhi appears to suggest that the Yamato paramount, Himiko, was the “Queen of the Wa” only through the consensus of other polities, but clearly there were other countries in the archipelago that did not subscribe to her blog, as it were, as they were in open conflict with Yamato.

This all leads into something we’ve talked about in the main podcast at various times, but it still bears discussing: How did Yamato, over in the Nara Basin, become the center of political life in the Japanese archipelago, and why not somewhere in Kyushu, like ancient Na or Ito? While we don’t entirely know, it is worth examining what we do and some of the factors that may have been in play.

After all, Kyushu was the closest point of the main Japanese islands to the mainland, and we see that the Yayoi culture gets its start there. From there, Yayoi culture spread to the east, and if we were to apply similar assumptions as we do on the spread of the keyhole shaped kofun, we would assume that the culture-givers in the west would have held some level of prestige as groups came to them to learn about this new technology, so why wasn’t the capital somewhere in Kyushu? We likewise see other such things—Yayoi pottery styles, fired in kilns, rather than open fired pottery; or even bronze items brought over from the continent. In almost every instance, we see it first in Kyushu, and then it diffuses eastward up to the edge of Tohoku. This pattern seems to hold early on, and it makes sense, as most of this was coming over from the continent.

Let’s not forget, though, that the Yayoi period wasn’t simply a century: by our most conservative estimates it was approximately 600 years—for reference, that would be roughly equivalent to the period from the Mongol invasions up to the end of the Edo period, and twice as long as the period from Mimaki Iribiko to the Naka-no-Oe in 645, assuming that Mimaki Iribiko was ruling in the 3rd century. So think about all that has happened in that time period, mostly focused on a single polity, and then double it. More recent data suggests that the Yayoi period may have been more like an 1100 to 1300 year range, from the earliest start of rice cultivation. That’s a long time, and enough time for things in the archipelago to settle and for new patterns of influence to form. And while Kyushu may have been the first region to acquire the new rice growing technology, it was other areas around the archipelago that would begin to truly capitalize on it.

We are told that by the time the Wei envoys arrived that the state of Yamato, which we have no reason not to believe was in the Nara Basin, with a focus on the area of modern Sakurai, had approximately 70,000 households. That is huge. It was larger than Na, Ito, and Matsuro, combined, and only rivaled in the Weizhi by Touma-koku, which likely referred to either the area of Izumo, on the Japan Sea coast, or to the area of Kibi, along the Seto Inland Sea, both of which we know were also large polities with significant impact in the chronicles.

And here there is something to consider about the Yayoi style agriculture—the land determined the ultimate yield. Areas with more hills and mountains are not as suited to wet rice paddy agriculture. Meanwhile, a flat basin, like that in Yamato, which also has numerous rivers and streams draining from the surrounding mountains into the basin and then out again, provided the possibility for a tremendous population, though no doubt it took time to build.

During that time, we definitely see evidence of the power and influence of places like Na and Ito. Na sent an embassy to the Han court—an incredible journey, and an indication of not only their interest in the Han court and continental trade, but also their ability to gather the resources necessary for such a journey, which likely required some amount of assistance from other, nearby polities. Na must have had some sway back then, we would assume.

Meanwhile, the burial at Ito shows that they were also quite wealthy, with clear ties to the continent given their access to large bronze mirrors. In the absence of other data, the number and size of bronze mirrors, or similar bronze items, likely only useful for ritual purposes, indicates wealth and status, and they had some of the largest mirrors as well as the largest collection found for that period. Even into the stories in the Nihon Shoki and the Kojiki we see how mirrors, swords, and jewels all are used a symbols of kingship. Elite status was apparently tied to material items, specifically to elite trade goods.

Assuming Yamato was able to grow its population as much as is indicated in the Weizhi, then by the 3rd century, they likely had the resources to really impress other groups. Besides things like mirrors, we can probably assume that acquisition of other goods was likewise important. Both Ito and Yamato show evidence of pottery shards from across the archipelago, indicating extensive trade networks. But without any other differentiating factors, it is likely that Yamato, by the 3rd century, at least, was a real powerhouse. They had a greater production capacity than the other states listed in the Weizhi, going just off of the recorded human capital.

And this may answer a question that has been nagging me for some time, and perhaps others: Why did other states acquiesce to Yamato rule? And the answer I keep coming back to is that it was probably a combination of wealth, power, prestige, ritual, and time.

For one thing, wealth: Yamato had it. That meant they could also give it. So, if Yamato was your friend, you got the goods, and you had access to what you need. You supported them, they could help you with what you needed. These transactional alliances are not at all uncommon, and something I think most of us can understand.

There is also power—specifically military power. With so many people, Yamato would likely have been a formidable threat should they decide that violence was the answer. That said, while we read of military campaigns, and no doubt they did go out and fight and raid with the best of them, it’s expensive to do so. Especially exerting control over areas too far out would have been problematic, especially before writing AND horses. That would be costly, and a drain on Yamato’s coffers. So while I do suspect that various military expeditions took place, it seems unlikely that Yamato merely bested everyone in combat. Military success only takes you so far without constant maintenance.

And so here is where I think prestige and ritual come into play. We’ve talked about how Yamato did not exactly “rule” the archipelago—their direct influence was likely confined to the Kinki region for the longest period of time. And yet we see that they influenced people out on the fringes of the Wa cultural sphere: when they started building large, keyhole shaped kofun for their leaders, and burying elites only one to a giant mound, the other areas of Japan appear to have joined in. Perhaps Yamato was not the first to build a kofun for a single person, but they certainly were known for the particular shape that was then copied by so many others. But why?

We don’t know for certain, but remember that in Yamato—and likely the rest of the Wa cultural sphere—a large part of governance was focused on ritual. The natural and what we would consider the supernatural—the visible and invisible—worked hand in hand. To have a good harvest, it required that workers plant, water, harvest, etc. in the right seasons and in the right way. Likewise, it was considered equally important to have someone to intercede with the kami—to ensure that the rains come at the right time, but not too much, and a host of other natural disasters that could affect the crop.

And if you want to evaluate how well ritual works, well, look at them. Are you going to trust the rituals of someone whose crops always fail and who barely has a single bronze mirror? Or are you going to trust the rituals of someone with a thriving population, multiple mirrors, and more? Today, we might refer to this as something like the prosperity gospel, where wealth, good health, and fortune are all seen as stemming from how well one practices their faith, and who’s to say that back in the day it wasn’t the same? Humans are going to human, after all.

So it makes sense that one would give some deference to a powerhouse like Yamato and even invite their ritualists to come and help teach you how it is done. After all, the local elites were still the ones calling the shots. Nothing had really changed.

And here is where time comes in. Because over time what started as an alliance of convenience became entrenched in tradition. Yamato’s status as primus inter pares, or first among equals, became simply one of primus. It became part of the unspoken social contract. Yamato couldn’t push too hard on this relationship, at least not all at once, but over time they could and did demand more and more from other states.

I suspect, from the way the Weizhi reads, that Yamato was in the early stages of this state development. The Weizhi makes Queen Himiko feel like something of a consensus candidate—after much bickering, and outright fighting, she was generally accepted as the nominal paramount. There is mention of a male ruler, previously, but we don’t know if they were a ruler in Yamato, or somewhere else, nor if it was a local elite or an earlier paramount. But not everyone in the archipelago was on board—Yamato did have rivals, somewhere to the south (or north?); the directions in the Weizhi are definitely problematic, and it may refer to someone like the Kuma or Kumaso people in southern Kyushu or else people that would become known as the Emishi further to the east of Yamato.

This lasted as long as Yamato was able to continue to demonstrate why they were at the top of this structure. Theoretically, anyone else could climb up there as well, and there are certainly a few other powerful states that we can identify, some by their mention and some by their almost lack of mention. Izumo and Kibi come to mind almost immediately.

The Weizhi makes it clear that Himiko’s rule was not absolute, and part of her reaching out to the Wei in the first place may have been the first attempt at something new—external validation by the continent. A large part of international diplomacy is as much about making people believe you have the power to do something as actually having that power. Getting recognition from someone like the Wei court would further legitimize Yamato’s place at the top of the heap, making things easier for them in the long run.

Unfortunately, it seems like things did not go so smoothly, and after Himiko’s death, someone else came to power, but was quickly deposed before a younger queen took over—the 13 year old Toyo. Of course, the Wei and then the Jin had their own problems, so we don’t get too many details after that, and from there we lose the thread on what was happening from a contemporary perspective. Instead, we have to rely on the stories in the Nihon Shoki and Kojiki, which are several hundred years after the fact, and clearly designed as a legitimizing narrative, but still present us something of a picture. We don’t see many stories of local elites being overthrown, though there do seem to be a fair number of military campaigns. Nonetheless, even if they were propped up by Yamato, local elites likely had a lot of autonomy, at least early on, even as they were coopted into the larger Yamato umbrella. Yamato itself also saw ups and downs as it tried to figure out how to create a stable succession plan from one ruler to the next. At some point they set up a court, where individuals from across the archipelago came and served, and they created alliances with Baekje, on the peninsula, as well as with another polity which we know of as Nimna. Through them, Yamato continued to engage with the continent when the dynastic struggles there allowed for it. The alliance with Baekje likely provided even more legitimacy for Yamato’s position in the archipelago, as well as access to continental goods. Meanwhile the court system Yamato set up provided a means for Yamato to, itself, become a legitimizing factor.

Hierarchical differences in society were already visible in the Yayoi period, so we can generally assume that the idea of social rank was not a new concept for Yamato or the other Wa polities. This is eventually codified into the kabane system, but it is probably likely that many of the kabane came about, originally, as titles of rank used within the various polities. Yamato’s ability to claim to give—or even take away—that kabane title, would have been a new lever of power for Yamato. Theoretically, other polities could just ignore them and keep going on with their daily lives, but if they had already bought into the social structure and worldview that Yamato was promoting, then they likely would have acquiesced, at least in part, to Yamato’s control.

Little by little, Yamato’s influence grew, particularly on those closer to the center. Those closer, and more affected, started to listen to Yamato’s rules about kofun size and shape, while those further on the fringes started to adopt Yamato’s traditions for themselves, while perhaps maintaining greater independence.

An early outlier is the Dazai. It is unclear whether this was forcibly imposed on the old region of Na and nearby Ito, or if it was more diplomatically established. In the end, though, Yamato established an outpost in the region early on, almost before they started their practice of setting up “miyake”, the various royal granaries that appear to have also become local Yamato government offices in the various lands. The Dazai was more than just a conduit to accept taxes in the form of rice from various locals—it was also in charge of missions to the continent. Whether they were coming or going, military or diplomatic, the Dazai was expected to remain prepared. The early iterations were likely in slightly different locations, and perhaps not as large, but still in roughly the area near modern Fukuoka and Dazai. This was a perfect place not only from which to prepare to launch or receive missions from the continent, but also to defend the nearby Shimonoseki straits, which was an important entryway into the Seto Inland Sea, the most direct route to Naniwa and the Yamato court.

The first iterations of direct Yamato control in Tsukushi—modern Fukuoka—claim to have been focused largely on being a last point to supply troops heading over to fight on the peninsula, not unlike the role of Nagoya castle on the Higashi-Matsuura peninsula in the 16th century. Over time, though, it grew into much more. The Weizhi, for its part mentions something in the land of Ito, where there were rooms set up for envoys from the continent, but the Dazai was this on steroids.

Occasionally we see evidence of pushback against Yamato’s expansion of powers. Early on, some states tried to fool the envoys into thinking that they were Yamato, perhaps attempting to garner the trade goods for themselves and to take Yamato’s place as the interlocutor between the Wa polities and the continent. We also see outright rebellions—from Iwai in Kyushu, in the 6th century, but also from various Emishi leaders as well. The Iwai rebellion may have been part of the impetus for setting up the Dazai as a way to remotely govern Tsukushi—or at least help keep people in line. For the most part, though, as time goes by, it would seem that Yamato’s authority over other polities just became tradition, and each new thing that Yamato introduced appears to have been accepted by the various other polities, over time. This is likely a much more intricate process than even I’m describing here, but I’m not sure that it was necessarily a conscious one; as the concept of Yamato as the “paramount” state grew, others ceded it more and more power, which only fed Yamato’s self-image as the paramount state. As the elites came under the Yamato court and rank system, they were more closely tied to it, and so Yamato’s increased power was, in a way, passed on to them as well. At least to those who bought in.

By the 5th century, we know that there were families sending people to the court from as far away as Hi no Kuni in Kyushu—near modern Kumamoto—and Musashi no Kuni in the east—including modern Saitama.

All of that said, while they may have subordinated themselves to Yamato in some ways, the various polities still maintained some independent actions and traditions. For example, whatever their connection to Yamato, the tombs at Itoshima also demonstrate a close connection to the peninsula. The horizontal entry chamber style of tomb—something we saw a lot in Iki, and which seems to have been introduced from the continent—started to become popular in the latter half of the 4th century, at least in the west of the archipelago. This is well before we see anything like it in Yamato or elsewhere, though it was eventually used across the archipelago. Itoshima appears to have been an early adopter of this tomb style, picking it up even before the rest of the archipelago caught on, making them the OG horizontal chambers, at least in Japan.

Ultimately, the image we have of Ito-koku is of an apparently small but relatively influential state with some influence on the cross-strait trade, with close ties to Yamato.

The history of the region seems a bit murky past the Kofun period. There are earthworks of an old mountain castle on Mt. Raizan that could be from the Asuka period, and in the 8th century the government built Ito castle on the slopes of Mt. Takaso, possibly to provide some protection to the Dazaifu, which was the Yamato outpost in Kyushu, and eventually became the main administrative center for the island. It seems, then, that whatever power the country of Ito may have once had, it was subsumed by the Dazai, which was built a little inland, east of the old Na territory. Furthermore, as ships grew more seaworthy over time, they could make the longer voyages straight to Iki or Tsushima from Hakata. For the most part, the area of the Itoshima peninsula seems to have been merely a set of districts in the larger Tsukushi and then the Chikuzen provinces.

The area of Na, meanwhile, which is said to have had 20,000 households in the 3rd century—much larger than nearby Ito—was completely eclipsed by the Dazaifu after the Iwai rebellion. After the fall of Baekje, the Dazaifu took on even greater administrative duties, and eventually took over all diplomatic engagement with the continent. They even set up a facility for hosting diplomatic envoys from the continent. This would come to be known as the Kourokan, and they actually found the ruins of it near the site where Maizuru castle was eventually built in what is now Chuo-ku, or the central ward, of Fukuoka city.

From the Heian period onwards, the Harada family eventually came to have some power in the area, largely subordinate to others, but they built another castle on Mt. Takaso, using some of the old Ito Castle earthworks, and participated in the defense of the nation during the Mongol invasions.

The Harada family rose briefly towards the end of the Sengoku Period, pushing out the Otomo as Hideyoshi’s campaign swept into Kyushu. They weren’t quite fast enough to join Hideyoshi’s side, though, and became subordinate to Kato Kiyomasa and eventually met their end during the Invasions of Korea.

The Ito district at some point after that became part of the So clan’s holdings, falling under Tsushima’s purview, along with a scattering of districts elsewhere, all likely more about the revenue produced than local governance. In the Edo period, there were some efforts to reclaim land in Imazu bay, further solidifying links with the Itoshima peninsula and the mainland, but that also fits in with the largely agricultural lifestyle of the people in the region. It seems to have remained largely a rural backwater up into modern times, when the Ito and Shima districts were combined into an administrative district known as “Itoshima city”.

Meanwhile, the Dazaifu continued to dominate the region of modern Fukuoka. Early on, worried about a Silla-Tang alliance, the Yamato state built massive forts and earthworks were built around the Dazaifu to protect the region from invasion. As the Tang dynasty gave way to the Song and Yuan dynasties, however, and the Heian court itself became more insular, the Dazaifu’s role faded, somewhat. The buildings were burned down in the 10th century, during the failed revolt of Fujiwara no Sumitomo. The government never rebuilt, and instead the center of regional government shifted to Hakata, closer to the bay.

Appointed officials to the Dazai were known as the Daini and the Shoni. Mutou Sukeyori was appointed as Dazai Shoni, the vice minister of the Dazaifu, in the late 12th century. Though he had supported the Taira in the Genpei wars, he was pardoned and made the guardian of Northern Kyushu, to help keep the region in check for the newly established Kamakura Bakufu. He would effectively turn that into a hereditary position, and his family became known as the “Shoni”, with their position eventually coming to be their family name. They would provide commendable service against the Mongol invasion, and eventually became the Shugo Daimyo over much of western Kyushu and the associated islands, though not without pushback from others in the region.

Over time, the power of the Shoni waned and various other daimyo began to rise up. The chaos of the Sengoku period saw the entire area change hands, back and forth, until Hideyoshi’s invasion of Kyushu. Hideyoshi divided up control of Kyushu, and Chikuzen, including the areas of Hakata and modern Itoshima, was given to Kobayakawa Takakage. Hideyoshi also began to redevelop the port of Hakata. After the battle of Sekigahara, Kobayakawa Hideaki, Takakage’s adopted son and nephew to the late Hideyoshi, was transferred to the fief of Okayama, and the area of modern Fukuoka city was given to Kuroda Nagamasa, creating the Fukuoka Han, also known as the Kuroda Han.

Nagamasa would go on to build Maizuru Castle on the other side of the Naka river from the port of Hakata, creating two towns with separate administration, each of which fell under the ultimate authority of the Kuroda. Hakata, on the east side of the river, was a city of merchants while Fukuoka was the castle town, and largely the domain of samurai serving the Kuroda. The Kuroda would remain in control of the Fukuoka domain through the Edo period, and only lost control at the very start of the Meiji, as the domain system in general was dissolved. Over that time, Hakata remained an important port city, and the samurai of Fukuoka were known for maintaining their martial traditions.

In the Meiji era, samurai from the Kuroda Han joined with other Kyushu samurai, rising up during Saigo Takamori’s rebellion. Later, it would be former samurai and others from Fukuoka who would form the Gen’yosha, an early right wing, nationalist organization that would greatly influence the Japanese government heading into the latter part of the 19th and early 20th century.

But that is getting well into more modern territory, and there is so much else we could discuss regarding the history of this area, and with any luck we will get to it all in time. For now, this concludes our Gishiwajinden Tour—we traveled from Kara, to Tsushima and Iki, and then on to Matsuro, Ito, and Na. From here the envoys traveled on to Fumi, Toma, and then Yamato. Fumi and Toma are still elusive locations, with various theories and interpretations as to where they were. For us, this was the end of our journey.

Next episode we will be back with the Chronicles and getting into the Taika era, the era of Great Change. There we will really see Yamato starting to flex its administrative muscles as it brings the various polities of the archipelago together into a single state, which will eventually become known as the country of Nihon, aka Japan.

Until then, thank you for listening. If you like what we are doing, tell your friends and feel free to rate us wherever you listen to podcasts. If you feel the need to do more, and want to help us keep this going, we have information about how you can donate on Patreon or through our KoFi site, ko-fi.com/sengokudaimyo, or find the links over at our main website, SengokuDaimyo.com/Podcast, where we will have some more discussion on topics from this episode.

Also, feel free to reach out to us at our Sengoku Daimyo Facebook page. You can also email us at the.sengoku.daimyo@gmail.com.

Thank you, also, to Ellen for their work editing the podcast.

And that’s all for now. Thank you again, and I’ll see you next episode on Sengoku Daimyo’s Chronicles of Japan.

References

Aston, W. G. (1972). Nihongi, chronicles of Japan from the earliest times to A.D. 697. London: Allen & Unwin. ISBN0-80480984-4