Previous Episodes

- June 2025

- May 2025

- April 2025

- March 2025

- February 2025

- January 2025

- December 2024

- November 2024

- October 2024

- September 2024

- August 2024

- July 2024

- June 2024

- May 2024

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

This episode, as Okinaga Tarashi Hime is preparing her troops to cross the straits and seek out the land of “gold and silver” that the kami have promised her, we’ll take a moment to look at the peninsula and just what has been going on over there in the late 3rd to early 4th centuries, because this is when we see the peninsula enter into the Three Kingdoms period, with the countries of Baekje and Silla rising to meet the elder state of Goguryeo and becoming kingdoms in their own right.

Before we get too much into that, let me address a few things.

First, I don’t speak Korean, and so my apologies up front if I butcher any of these names. I’ll do the best I can. Also, on the spelling: There are various ways of turning Hangul, the Korean writing system, into Latin characters. So sometimes you’ll see Goguryeo, Baekje, and Silla, and sometimes you’ll see Koguryo, Paekche, and Silla. For the most part I’ll be using the Revised Romanization (Gug-eoui Romaja Pyogibeop) as opposed to the McCune-Reischauer system, but since I’m not always familiar with things, forgive me if I slip up from time to time.

A general idea of the locations of the Samhan, or Three Han, of the Korean Peninsula. Map by Idh0854, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons.

So where are all these places we are talking about? Well, let’s first look at the location of the Samhan, or Three Han. By the way, it can get very confusing because generally I use “Han” in the meaning of the ethnic Han people in the area that is, today, modern China, including the various empires that were inspired by them (though those empires were not always properly “Han” in that context). (漢 / 汉) However “Han” is also the reading of the character that the old chronicles, like the Wei Chronicles, used to discuss three of the groups on the Kroean peninsula, and it also happens to be the term used in Korean for Korea itself (韓). For the most part, if I’m talking about the “Han” I’ll be referring to those people who came over from the areas of modern China, and not the early inhabitants of the peninsula.

Now exactly where these groups were is vague. It isn’t like anyone laid out a geographic map with borders. And there were other groups as well on the peninsula, even though we mostly concern ourselves with these three. So the map here gives a rough approximation of their location. The Commanderies would have been above them, to the north, and then the states of Okjeo, Goguryeo, and Buyeo beyond that.

Map of the Korean Peninsula showing the Three Kingdoms and Gaya. This is roughly showing the extent of the kingdoms in about 476. Used under CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

After Goguryeo defeats the commanderies, and pushes them off of the peninsula, then the three kingdoms are able to take over most of the peninsula. The map here is actually of the borders in about 476—so about a hundred years after the time we are discussing—but it gives a general idea of where we are talking about. Of all of these, I’d say that Goguryeo probably has the most dramatic shift in borders. Then again, being at the northern end of the peninsula with access to the Manchurian massif and the Eurasian steppes, they have the greatest ability to expand, but also face the most threats in the form of other actors encroaching on their borders, while in the rest of the peninsular kingdoms they have at least one back to the ocean.

And, remember, other than Goguryeo, the Kingdoms generally weren’t being written about until after the fall of the Commanderies, and so we don’t exactly have great records for their full extent until much later.

-

Welcome to Sengoku Daimyo’s Chronicles of Japan. My name is Joshua and this is episode 39: The Birth of the Three Kingdoms.

Alright, so we’ve been dealing with the Chronicles up through the fourteenth sovereign, Tarashi Naka tsu Hiko, more popularly known as Chuuai Tennou. By my calculations, we are somewhere in the mid to latter 4th century, even if the Nihon Shoki claims we are just at the end of the 2nd century. This was a momentous time on the peninsula, seeing the rise of native rule after the fall of the Han Commanderies, and the events there were having rippling effects throughout both the peninsula and the islands. You know, it is so easy for us to assume that because Japan is an island nation that it was somehow disconnected from the events on the mainland, like the straits and seas were a moat that kept everyone out. And yet, while they certainly did allow Japan to maintain some distance, they were hardly an iron wall, and Japan was often impacted by what happened with her neighbors, especially as time went on and things were becoming more and more connected. In a way, you could see this as the natural extension of the connections that we are seeing mentioned in the Chronicles, with Yamato dominion having been extended from Tohoku in the northeast all the way to Kyushu.

In the 4th century, the archipelago seems to have had at least good trade relations with the Gaya kingdoms, as we’ve mentioned before. To recap, Gaya was a confederation of small states that may have even become a kingdom, based in the old Pyonhan area, one of the three groups of city-states, this one around Gimhae and the Nakdong River region. While not confirmed, I highly suspect that the Pyonhan were—or at least included—a peninsular Wa people, possibly speaking their own form of peninsular-Japonic. If that is the case, then the states of the Gaya confederacy might be seen as simply an extension of the culture that had spread with the Yayoi into the Japanese archipelago, though no doubt, over time, those on the peninsula would have had more blending and interaction with the other people there.

From what it looks like, the Korean peninsula at this time was a diverse region. You likely had Han Chinese, Japonic-speaking Wa people, as well as others, such as the Buyeo people in Goguryeo and Baekje. There were many other groups mentioned in the Annals and Histories, such as the Ye, the Maek, the Malgal, and others, though whether they had distinct linguistic traditions or were simply different political groups, it is hard to say. Since we don’t have any indigenous chronicles for them we are largely left to conjecture based on what others have written about them. But regardless of the cultural and linguistic diversity, in broad strokes we can talk about the formation of three main powers. I will emphasize that these strokes are necessarily broad—I think it would be awesome to do an in depth discussion of Korean history, but that just isn’t our main focus. So please don’t yell at me for skipping over your favorite story from this period—we have a lot to cover.

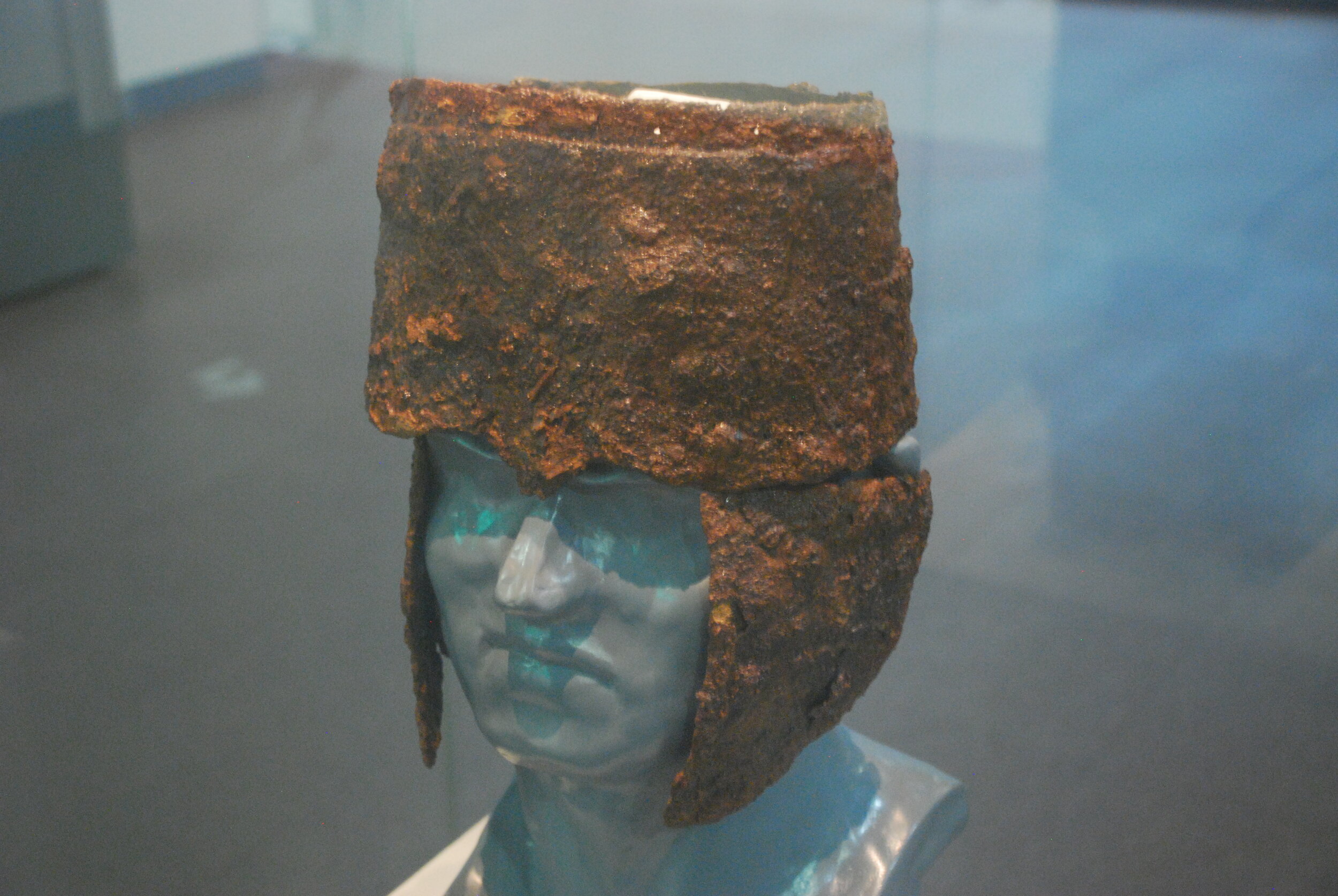

So the Three Kingdoms that we are focused on here are Goguryeo, Baekje, and Silla. We’ve talked about the Gaya confederation some in the past, and we may touch on them, but really I want to talk about the reason why the 4th century is considered the start of the “Three Kingdoms” period on the peninsula. And no, these are not the same as the Three Kingdoms, or San-guo, of China. No Cao Cao with a duck on his head. Sorry. Though some of the peninsular aristocracy did have some totally bitchin’ headgear. I’m just saying.

I want to try to talk about these as best we can, and to do that we’ll be looking at some other sources, including the Korean chronicles of the Samguk Sagi and the Samguk Yusa, which tell the tales of the “Three Kingdoms” of Baekje, Goguryeo, and Silla. However, as sources go, we need to be aware that these are even further than the source material than the Nihon Shoki and the Kojiki, having been written centuries later. The Samguk Sagi, or “history of the three kingdoms”, was commissioned by the Korean Goryeo dynasty, and compiled by Kim Busik in 1145. It seems that this largely drew on various extant chronicles that we no longer have and compiled them into a single work. In fact, the Nihon Shoki mentions various Korean annals that were referenced in its own compilation. One interesting note, though, it seems that Kim Busik didn’t try to integrate all of these into a single narrative. Rather, the annals of each kingdom are told largely separately, meaning it reads something like Kurosawa’s “Rashomon”—or even the original “In a Grove”—with several different perspectives on the same event.

The Samguk Yusa, or “Memorabilia of the Three Kingdoms”, focuses more on the stories and less on the chronicled history. It was probably put together by a monk by the name of Iryeon in the 13th century, but that is a lot less clear.

Like the Japanese Chronicles, both of these were written entirely in a Korean form of Chinese, using Chinese characters for both meaning and pronunciation. On the other hand, they likely had reliable textual references dating back much earlier than the archipelago, given their proximity to the various continental empires. That means that the peninsula likely had a more robust literary culture than the islands seem to have had. After all, the peninsular kingdoms had been right on the border of Wei and Jin empires, and both they and the ethnic Han commanderies utilized writing for all sorts of purposes, including the administration of the state. Bordering states would have likely been expected to pay tribute or otherwise appease the commanderies and the court at Louyang of which they were an extension. As such, one can only assume that they ended up adopting and adapting the tools of statecraft that they knew, which would have included reading and writing.

In the archipelago, on the other hand, there is no indication of this same kind of literary tradition—definitely not to the same extent. It certainly may be the case that there were those who could read and write, at least enough to send correspondence to the Wei court, back in the time of Himiko, but it is unclear if that was actually the Wa themselves, or perhaps Han immigrants in their midst. There may have even been decorative or performative writing—that is, writing that was done more as a performance or decoration than for any actual communication. This may be what we are seeing when we catch glimpses of what could be Sinitic characters on clay pots and similar media early on. But there is no indication of widespread use nor of an understanding of writing as a means of supporting the government.

I mean, think about it for a moment. When you consider a government, what do you have? Sure, at the top you have the leaders and people making decisions, whether a king, a president, a prime minister, and various legislative and judicial bodies. But other than arguing, what do the majority of people in a government do? A lot of them are either collecting data on the state of the country and sending that to someone, or they are implementing the policies being directed down from the top. That is something that is possible to some extent without writing, but it quickly gets to be unwieldy. Sure, you can rely on a network of individuals, but how reliable are they?

So writing may not be absolutely essential for the formation of a state—look at the incredible Incan empire in the Americas—but it is certainly extremely helpful, especially when you are trying to govern large regions of territory. And some of the earliest writing is really about keeping track of stuff—inventory, taxes, etc.

So it is quite likely that the peninsular kingdoms had some form of literary traditions, no doubt based on what they had learned from their Han neighbors, though these weren’t always long traditions, and weren’t necessarily being used to document historical fact. After all, as just about anyone in IT can tell you, most people don’t exactly focus on documentation first and foremost. Baekje, for instance, was possibly just starting to really keep court records around the mid-4th century—which could also be because, despite the claims made about the state’s history, it was actually relatively new to the scene at that point, which we’ll talk about.

Now, just because they wrote things down doesn’t mean that their sources are any more or less infallible. Indeed, there is some consideration that the historiographical methods of the Japanese court, designed to promote the story of the royal family, was something that they came by honestly from their peninsular teachers. So we can’t exactly treat the Samguk Yusa nor the Samguk Sagi as accurate in all things. In fact, it is very clear that they seem to have postulated much earlier dates for some events than seems at all possible, and, like with the Kojiki and the Nihon Shoki, as the centuries progress they get more and more reliable.

But let’s actually get into the history of the Three Kingdoms, themselves.

We should probably start in the north, because while the rest of the peninsula was still divided up into the Samhan, or three Han, each of which was made up of multiple independent polities, up in the north you already had one of your first of these three Korean states. This was Goguryeo, or sometimes even just “Goryeo”, which is actually where the English name, “Korea” is derived. Goguryeo was largely at the head of the peninsula and expanded into the continent. While the territory governed by the state would vary, at its height it ranged from the area of Harbin, in modern China, and, at its height, south into the northern parts of modern-day South Korea, encompassing all of modern North Korea.

Now you may recall that we discussed Goguryeo previously, and their on-again, off-again relation with the Han Commanderies. Sure, the Wei loved Goguryeo when they were helping them to take down their rivals on the Liaodong peninsula, just to the West, but it didn’t take much for that alliance to break apart, especially once the other threats had been eliminated. When Goguryeo attempted to expand southward, hoping to get access to much needed farmland, the Wei saw that as a provocation dealt a considerable blow to Goguryeo, driving them from their capital city in 244.

Goguryeo was down, but not entirely out. A second Wei invasion in 259 seems to have turned out not quite so well for the Wei, and they were defeated at Yangmaenggok. Nonetheless, the damage to Goguryeo was significant, and it would be years before they were again a major threat to the Commanderies or anyone else on the peninsula.

In fact, during the 2nd half of the 3rd century, much of Goguryeo’s bloodshed was internal, within the royal court. This seems to have culminated in the last decade of that century in the rise to power of one of Goguryeo’s most ruthless kings, King Bongsang.

According to the stories we have, Bongsang was quite the disagreeable figure. Arrogant and downright paranoid. Of course, he may have had a reason to be worried, but largely those seem to be reasons of his own making. As soon as he rose to power in 292, he had his own uncle, Prince Anguk, executed. Now Prince Anguk wasn’t just some dandy with royal blood, but back during the previous reign, that of Bongsang’s father, he had been helping his brother, the king, defend Goguryeo. The man was a frickin’ war hero, and quite popular with the people. King Bongsang didn’t care, and being the paranoid and insecure man that he was, only saw this as a threat to his own power, so he had him labeled as a traitor and killed.

And of course that totally blew up in his face. Killing the beloved war hero--I mean, really, when has that really worked? Bongsang’s plan seems to have been that if he labelled him as disloyal then it would kill any support the people had for him, but instead Prince Anguk’s death seems to have only riled up the populace against the King. He turned him into a martyr.

As if that wasn’t enough, he would try again, only a year later. This time he accused his own younger brother of plotting against him, and he made him commit suicide.

Now his brother’s son—that is Bongsang’s nephew—clearly saw the writing on the wall and decided to get out of Dodge. Known as Prince Eulbul, he apparently took on the life of a servant to hide as a commoner, taking on various menial tasks and doing his best not to catch his uncle’s eye. And when I say menial, I mean it. At one point he was in a job where he was throwing rocks into a pond at night so that the frogs wouldn’t wake up his master. How’s that for a night shift? He actually ran away from that job to find one where he had to do more physical labor, but at least he wasn’t up all night on frog duty.

And while Prince Eulbul was trying to figure out what options were open to him now that “Prince” was apparently out of the question, things weren’t getting any better at the court, and eventually, the court itself had enough. Bongsang’s own prime minister, a man by the name of Chang Jori, resigned his position and, along with other disaffected ministers, he planned and executed a successful coup, overthrowing King Bongsang in 300 CE. King Bongsang and his two sons were both exiled, but they all committed suicide rather than go on frog duty, themselves.

With the throne empty, Chang Jori and the other ministers decided that they needed to find a new monarch, and so they instituted a search throughout the land, eventually tracking down Prince Eulbul. Of course, the Prince thought this might be a trick—he hadn’t exactly been plugged into court politics for the past eight years, and he tried to deny who he was, but eventually they explained to him the situation and he was reinstated and then enthroned as King. Posthumously known as King Micheon, he grew the Goguryeo military, and had an extremely successful career, being known as one of Goguryeo’s better rulers. He expanded back into the Liaodong peninsula, and turned his attention to the old Han Commanderies.

Now the Wei had long since fallen and given way to the Jin dynasty, but the Jin itself was in trouble and unable to provide the support to its outposts as it once did. Still, at the beginning of the 4th century, the peninsula was not exactly forgotten. In fact, political rivals were often sent to the commanderies as a form of exile, sending them to the very edges of the empire.

Nonetheless, the commanderies were not what they once were, and Goguryeo forces began to attack the representatives of Jin power on the peninsula. First they attacked and destroyed the Xuantu Commandery in 302, which was the northernmost of the three commanderies still on the peninsula. Later they annexed the Lelang and Daifang commanderies in 313 and 314, effectively ending any official Jin presence on the peninsula, though there remained some ethnic Han citizens who stayed and seemed to have thrived, at least through the middle of the 4th century. Han tombs and their contents tell us that even if the Commanderies were no longer present, it doesn’t mean that all of the Han were wiped out, and in fact some seem to have done quite well for themselves.

After the defeat of the Commanderies, Eulbul turned his attention largely to the west, where he spent much of his time embroiled in conflicts with the Xianbei in the area of the Liaodong Peninsula. This continued throughout Eulbul’s reign, right up until the king’s death in about 331 CE, and likely kept Goguryeo’s attention focused largely on their western neighbors, rather than on the peninsula itself.

Following Eulbul’s death his son, Sayu, came to the throne. He would posthumously be known as King Gogugwon. One of the first things he did was apparently expand the fortress at Pyongyang—and yes, that is the same Pyongyang as the modern capital of North Korea. Later, he would repair the old fortress of Hwando and build the city of Gungnae-song in its shadow. This was actually a common plan for Goguryeo cities at this time: a fortress would be built incorporating the natural rise of the mountains, and this would be a stronghold for the people to take cover in during times of war and strife. Outside would be built a walled city on a geometric plan—in this case a square-walled site near modern Ji’an, on the Chinese side of the Yalu River border with North Korea. This square-shaped walled city would be the site of daily activities in a time of peace.

Not that peace was in the cards for Sayu and Goguryeo. They continued to suffer attacks from Xianbei Murong and other steppe groups, until they were ultimately defeated and humiliated by the Xianbei Yan Kingdom around 342. The Xianbei dug up the body of Sayu’s father, the previous sovereign, King Micheon, and also captured Queen Ju, Sayu’s mother, and various concubines. Holding all of them, both the living and the dead, as hostages, they demanded Goguryeo’s surrender. Eventually, Sayu submitted to Yan as a vassal state, for which he received back his father’s body, but his mother was still held hostage for some time. Sayu moved the capital back down south to Pyongyang, and seems to have focused their attention back on their southern neighbors. In 369, some 27 years after their defeat by the Xianbei, Sayu led an army against the people to their south, perhaps in an attempt to reinvigorate Goguryeo. This would not exactly go as planned, and we’ll touch on that, later.

That said, the fall of the commanderies at the beginning of the 4th century had ripple effects throughout the peninsula. Up to that point, they had represented the major power on the peninsula, whether it was the Han, the Wei, or the Jin. There is plenty of evidence to suggest that they continually played the various polities of the three Samhan off of one another and kept them largely destabilized and, in a way, subservient to the Commanderies themselves. Without the commanderies, there would have been a power vacuum created—and this may be one of the factors leading to the rise of the other kingdoms on the peninsula.

The first of these that I want to touch on is the Kingdom of Baekje. Now according to the Baekje Annals in the Samguk Sagi, the Kingdom of Baekje was actually founded in about 18 BCE, but that date seems impossibly early based on what else we know. For instance, we know that in 290 there was an embassy to the Jin court sent by representatives of the various Mahan states. At that time there was one state known as Bochi, or Pai-chi, which may be an early name for Baekje, but it wasn’t even the most prominent of the states in Mahan. That honor seems to have gone to a state known as Wolchi-guk, or possibly Mokchi-guk, about which we have very little information.

Now according to most sources, the founding of Baekje was closely tied to the state of Goguryeo, and through them to the ancient state of Buyeo. Buyeo seems to have been a predecessor to the state of Goguryeo, founded around the 2nd century BCE and lasting until the late 5th century. Much of its territory seems to be in the middle of Manchuria, in modern Northeast China. The legendary founder of Goguryeo, King Jumong, is said to have been a descendant of the King of Buyeo, founding Goguryeo around 37 BCE. According to Baekje tradition, King Jumong had three sons: Yuri, Biryu, and Onjo. Yuri was born to a previous wife, and when King Jumong died Yuri suddenly showed up in Goguryeo to take the throne. Accordingly his half-brothers, Biryu and Onjo, decided that they wouldn’t wait around—and seeing how bloody things got in later family disputes in Goguryeo, I can’t exactly fault them for deciding to get out of Dodge altogether. They made their way south, to the 54 states of the Mahan. There they were accepted and set up two new kingdoms. Biryu set up the kingdom of Michuhol, while Onjo set up the kingdom of Sipje. When Biryu died, the people of his kingdom joined with the other Goguryeo refugees in Sipje, and the kingdom was renamed to Baekje. “Sipje” basically meant “10 subjects”, indicating the 10 allies who had come with Onjo to first found his new state, and “Baekje” replaces “10” with “100” indicating the new subjects that had arrived from his late brother’s kingdom.

Some time after this consolidation, Onjo and his descendants began to consolidate power, eventually subjugating or absorbing all of the states of Mahan.

Of course, as I mentioned earlier, the Annals claim this was sometime around 18 BCE, but that date seems extremely unlikely. I mean, granted, it isn’t some 8 centuries too early, like we find in the Japanese Chronicles, but it still doesn’t line up with what we actually know about the peninsula.

There is no evidence that there was any kind of major peninsular state south of the commanderies that early on. In fact, as we’ve mentioned, the Commanderies themselves would likely have done their best to stop any major states from forming. But besides that, if one did form, we would likely hear about it in the record.

Johnathan Best, who translated the Baekje Annals from the Samguk Sagi into English, has made an attempt to try to uncover just when the state of Baekje was likely founded—or at least when its Buyeo-descended royalty may have arrived. After all, there does seem to be a consistent theme that the Baekje royal family was connected to Buyeo, usually mediated through the state of Goguryeo, and there are various cultural artifacts that would seem to confirm a connection, at least between Goguryeo and Baekje.

So it seems that there may, indeed, be a connection to the Goguryeo royal lineage—and thus all the way back to the ancient state of Buyeo—but if so, it must have been much more recent than 18 BCE. What we know for certain is that Baekje was definitely a fully fledged nation by 372, when King Geungchogo sent his own embassy to Jin Court. This King, King Geungchogo, was also the first king of Baekje to have had official written records kept, so he is largely considered historical whereas the previous 12 or so kings back to Onjo are questionable.

Now if the royal line of Baekje did come from Buyeo stock, by way of Goguryeo, when could that have occurred? Well, Best suggests that it may have been around the turn of the 4th century, probably around the time of the cruel and capricious King Bongsang of Goguryeo, whom we talked about earlier in this episode. It is possible that in his cruelty, he drove out more than just Prince Eulbul. On the other hand, it could also have been that when Changjori and other ministers enacted their coup and placed Eulbul on the throne, well, there may have been continued supporters of Bongsang, or even rival princes, who decided that it was in their best interest to not hang around any more. After all, they had just been through a decade of bloody palace intrigue and there was no reason to think that the newly risen faction in court wouldn’t take their opportunity to enact vengeance upon their rivals.

Furthermore, it is not too improbable that these disaffected nobles and Goguryeo refugees may have found safe haven in the young states of Mahan—possibly even in an existing state known as Baekje-guk. Even though they may have been on the outs with their home kingdom, they were still nobles and they would have been experienced in the latest tools of statecraft on the peninsula. This is something we don’t often think about but understanding how to run a government is a skill in and of itself, and the art of government evolves and changes. Over time the tools and techniques developed in one country can be spread and adopted in others. This may have made these foreigners quite popular with the elite.

In addition, they seem to have been given leave to set up in the northern part of the Mahan territories, around the Han river system, near modern Seoul, creating a buffer, of sorts, between the Mahan and the commanderies.

And here we see several similarities in the archaeological record between Baekje and Goguryeo. For one thing, Baekje’s capital city was similar to that of the Goguryeo site of Hwando and Kungnaesong, in that it was a geometric walled city paired with a Goguryeo-style mountain fortress. We also see similarities in the tombs, which are built up like short, flat-topped pyramids. These would seem to suggest that there was, indeed, some connection between these two states, though there was also a certain enmity between them.

Now, although the dates found in the Baekje Annals are questionable, the overarching story of the early kings of Baekje is, itself, rather intriguing, and not entirely unbelievable. Early on in the Baekje Annals, the rulers of the young state take a subservient position amongst the other Mahan, with one individual seemingly at the head of the various Mahan states. Though far from holding direct rule over all the myriad countries, this individual did seem to hold the power to intervene in disputes and even shame the kings of Baekje, at least early on, into compliance. This may not be too dissimilar from the kind of coercive influence that early Yamato may have held in the archipelago.

Of course, as the state of Baekje grew, it soon turned the tables on its neighbors, absorbing the other states of the Mahan, and entering into constant struggles with its neighbors. To the north, the commanderies were pressing on the young state, and rallying up local groups, referred to in the Annals as the Malgal, to raid and harass Baekje.

Despite all of the attacks and apparent warfare, Baekje seems to have thrived, holding its own against the Commanderies until they fell to the Goguryeo King Micheon—the former Prince Eulbeul—in 313 and 314. With the commanderies gone, Baekje would have been free to continue its expansion across parts of the peninsula. It also may have freed up the talent of the ethnic Han bureaucrats and merchants, if the young peninsular states could attract them to their courts.

And here I want to pause for a moment. We talked about the make up of the Baekje royal family as one of Buyeo descent, as was Goguryeo, and many of the high-ranking court nobles seem to have made similar claims, but this was only the upper echelon of society. It is actually quite probable that the people that they ruled over were ethnically distinct, which would make sense if this was Goguryeo nobility ruling over a common Mahan people.

The fact is, we don’t really know all that much about the people of Mahan. Were they a single ethnicity or were they several different groups? Did they all speak a common language, even? What was it that caused the Han, Wei, and Jin chroniclers to differentiate between the three groups of Mahan, Byonhan, and Jinhan in the first place? Was it just for geographic simplicity, or was it something else?

I suspect that the Baekje rulers and their people likely spoke a different language, at least at first. Think of the Normans in England, though I don’t know if the relationship was so cut and dried as “rulers” and “subjects”. The main thing to note is that the peninsula was, from an early point, a very diverse and heterogenous place, with many different groups, including, we believe, people speaking some form of proto or peninsular Japonic, as well as Chinese and an early form of Korean—and probably more as well. It is quite possible that people were regularly bilingual and dealing in multiple languages, or possibly through some regional lingua franca. Whatever the reality, it is hard to uncover exactly. Over time, many of the place names on the peninsula—the very locations that would most likely have held onto traces of the original languages of the region—were deliberately changed and replaced. Today we tend to treat all of these names and locations as if they were spoken with a modern Korean pronunciation, just as we tend to do with Japanese names on the archipelago, but we should remember that the truth is likely to be much more complex.

Unfortunately, there isn’t much more that we really get on the common people in Baekje at this time. We have only scant glimpses at their religious and personal lives, with much of the action focused on things like meteorological events and the political and military accomplishments.

Speaking of which: as Baekje subjugated much of the Mahan, they also eyed the land of Jinhan, to the east, on the other side of the Peninsula, where another fledgling state was asserting its own dominance; Silla. This was one of the other states that would rise and become a significant power on the peninsula. At the same time, Baekje was also taking the fight to the north, and without those pesky Commanderies in the way, they came into conflict with Goguryeo. When King Sayu of Goguryeo marched south with his men, Baekje, under the rule of King Geunchogo, repulsed the invaders and counterattacked, eventually culminating in an assault on the fortress of Pyongyang in 371 CE. During the assault, a Baekje arrow found its mark, striking and killing the Goguryeo king, Sayu. Baekje seems to have been unable or unwilling to press the advantage, though, but they do seem to have moved their own capital northward, perhaps to better administer the territories of southern Pyongyang.

So that gives us a general idea of Baekje, but let’s take a look at the third kingdom that we see rising up at this time: Silla.

Much like Baekje, Silla makes no real appearance in other records before the 4th century. The Samguk Sagi suggests that it was formed before either Baekje or Goguryeo, with a claimed founding in 57 BCE. Once again, we have to wonder about such a date. More likely, an early state, by the name of Saro, likely arose in the midst of the other countries of Jinhan, and really started to grow into a regional power sometime in the late 3rd century.

Ignoring the dates, if we look at the Silla Annals in the Samguk Sagi we see evidence of its growth. Of all of the locations, it seems to have been one of the most cosmopolitan. Some of the people of Jinhan apparently claimed descent from the ethnic Han populations, claiming status as ancient refugees of the Qin, though this seems questionable at best. There were also members of the court who laid claim to Wa ancestry—and indeed the areas of Jinhan and Pyonhan—the area of the Kara confederacy, and likely home to a fair number of peninsular Wa people—both seemed to have shared a fair amount of material culture up until the late 3rd century, when we see them start to drift apart.

Silla’s legendary founder is known as Bak Hyeokgeose, and the stories say that he was born from a large egg. From there, the early history of Silla talks of dealing with the leader of the Mahan states as well as Wa pirate raiders along the coast. Soon, they are in conflict with Baekje, while also dealing with the other tribes and ethnic groups on the peninsula, such as the Ye and the Maek.

Silla built its capital in the plains of Gyeongju, where there certainly is a long history of occupation, at least according to the archaeological record. Silla’s own stories say that six villages came together to build the city of Gyeongju, and that may give an indiation of how this early state was born.

The capital of Silla, known from early times as “Seorabeol”, which may have just meant “capital”, was centered on the Gyeongju plain. At a bend in the river, a fortress was built on a half-moon shaped hill, known as half-moon fortress, and then four other fortresses guarded the city from atop nearby hillsides. This was quite different from the Goguryeo-style paired sites of a mountain fortress and a geometrically planned walled city.

Their burial practices were also different. They built wooden chambers, covered in dirt, much as the ethnic Han would do, but then they employed a trick learned from the Goguryeo, adding a layer of cobblestones before covering it all over again. Those cobblestones, and the lack of a corridor, were a type of anti-theft measure. Imagine digging into the side of a mound, and at first it is easy going—you have some grass, probably, but soon you are just pulling out dirt. You know that there is something in there, so you keep digging, and eventually you hit the cobblestones. At first this doesn’t seem so bad—you just grab the cobblestones and pull them out of there. Except, you are probably working from the bottom, and it is like you just pulled the fruit out from the bottom of the display. As soon as you do that, all the other cobblestones fall after it, filling in the hole you just made. Like Sisyphus, every inch you gain is taken away from you, and instead of digging a small hole to your target you end up digging away half the mountainside. It is really a rather simple and ingenious way to protect your dead kings and their stuff, and it worked remarkably well—we have a treasure-trove of items from ancient Silla, and a lot of it does seem to involve gold and silver, much as we heard in the Nihon Shoki, though when Silla really became known for their golden crowns and manufacturing techniques I couldn’t exactly say.

It’s possible that this came with the fall of the Commanderies and the movement of some of the ethnic Han into Silla. It may also be notable that the surname of the later Silla kings, “Kim”, is a reference to “Gold”.

Speaking of which, it is somewhat notable that the first twelve rulers of Silla were actually from one of two intertwined families, either the Bak or the Seok. The thirteenth sovereign was actually the first ruler from the Kim clan, which would eventually come to dominate the throne. The Kim clan’s status seems to have been solidified by the time of the kingdom’s 17th sovereign, Kim Naemul, who was also the first sovereign that could be corroborated in other historical sources, such as those of the Jin court, and even mentioned in the Japanese Chronicles. Naemul came to power around 356 and ruled through 402—basically the entirety of the latter 4th century.

Now, of all the annals in the Samguk Sagi, the Silla Annals are the most detailed. Even for these times that we believe are anachronistic, they have a lot of detail of the dealings of Silla with its neighbors. It seems that Silla grew, and just as Baekje absorbed the Mahan, Silla absorbed the Jinhan. Whereas Baekje was focused on the Mahan and the Commanderies, however, Silla seemed concerned with the Wa and with Gaya, to the south. It is unclear if the Wa mentioned in the Silla accounts are all from the archipelago or if some of them may have come from the peninsula. Over time there is definitely a distinction between the Wa and Gaya, however, indicating a clear distinction between them.

There are also numerous conflicts with Baekje. Baekje seems to be shown as an aggressor against Silla, while Silla is actively attempting to subjugate the areas of Gaya and Wa. Of course, if they are fighting with Baekje, and Baekje wasn’t really a power until the late 3rd or early 4th centuries, then we have some idea, possibly, of when many of these stories are actually taking place.

That said, none of this is constant warfare, but instead there are periods of fighting followed by a truce, and then eventually, more fighting. The root cause of many of the conflicts aren’t directly discussed—and it may simply have been enough that they were different states vying for supremacy. There were even other groups and people, but other than Gaya we don’t hear nearly as much from them, other than the occasional raiding party or alliance. Even Gaya seems to be an “outside” party on the peninsula. It is into this mix that the Wa would find themselves, and Yamato would enter the complex world of peninsular politics.

And I think that’s about where we will leave it. By the latter half of the 4th century, around the time that Okinaga Tarashi Hime is gearing up to head off from Kyushu, there were three major states on the peninsula, and then myriad other, smaller groups. Goguryeo in the north had destroyed the ethnic Han commanderies, but was still nursing its own wounds inflicted by the Murong Xianbei and Baekje. Baekje itself was just reaching the height of their power, and were even starting to encroach on the weakened Goguryeo as well as their Silla neighbors. Silla had established itself on the central eastern coastline, and was fending off attacks from, and attempting to subjugate, the loosely confederated states of Gaya to their south. Meanwhile there are attacks by the Wa, the Malgal, and the Ye and Maek. Up in the north, the ancient Okjo and Buyeo, whom we’ve really only barely mentioned, seem to be waning.

This is the early part of Three Kingdoms era on the Korean peninsula. These three states will vie with each other for the next several centuries. At the same time they are still developing their own policies and statecraft, borrowing from their Han neighbors, but also innovating their own ways of doing things. Over time, they would consolidate into a single state, but for now they were still fighting with one another.

Next episode, will get back to Okinaga Tarashi Hime and we’ll see how she fares as she jumps into the fray on the Korean Peninsula.

So, until next time, thank you for all of your support. If you like what we are doing, tell your friends and feel free to rate us on iTunes, Spotify, or wherever you listen to podcasts. If you feel the need to do more, and want to help us keep this going, we have information about how you can donate through our KoFi site, kofi.com/sengokudaimyo, or find the link over at our main website, SengokuDaimyo.com/Podcast, where we will have some more discussion on topics from this episode. Questions or comments? Feel free to Tweet at us at @SengokuPodcast, or reach out to our Sengoku Daimyo Facebook page.

That’s all for now. Thank you again, and I’ll see you next episode on Sengoku Daimyo’s Chronicles of Japan.

References

Kim, P., & Shultz, E. J. (2013). The 'Silla annals' of the 'Samguk Sagi'. Gyeonggi-do: Academy of Korean Studies Press.

Kim, P., Shultz, E. J., Kang, H. H. W., & Han'guk Chŏngsin Munhwa Yŏn'guwŏn. (2012). The Koguryo annals of the Samguk sagi. Seongnam-si, Korea: Academy of Korean Studies Press.

Jeon, H.-T. (2008). Goguryeo: In search of its culture and history. Seoul: Hollym.

Best, J. (2006). A History of the Early Korean Kingdom of Paekche, together with an annotated translation of The Paekche Annals of the Samguk sagi. Cambridge (Massachusetts); London: Harvard University Asia Center. doi:10.2307/j.ctt1tg5q8p

Shultz, E. (2004). An Introduction to the "Samguk Sagi". Korean Studies, 28, 1-13. Retrieved April 11, 2021, from http://www.jstor.org/stable/23720180

Iryŏn, ., Ha, T. H., & Mintz, G. K. (2004). Samguk yusa: Legends and history of the three kingdoms of ancient Korea. Seoul: Yonsei University Press.