Previous Episodes

- July 2025

- June 2025

- May 2025

- April 2025

- March 2025

- February 2025

- January 2025

- December 2024

- November 2024

- October 2024

- September 2024

- August 2024

- July 2024

- June 2024

- May 2024

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

This episode we look at some of the other goings-on during the reign of Nunakura Futodamashiki no Mikoto—especially as regards some of the cross-strait relations with Silla and Baekje, largely revolving around the status of the state of Nimna.

Who’s Who

Nunakura Futodamashiki no Mikoto, aka Bidatsu Tennō

The current sovereign, son of Ame Kunioshi—we are told he was not a Buddhist, but he did enjoy continental literature.

Nichira

Aka Nila or Illa (日羅), a name made up of the first character from “Nihon” (日本) and the last character of Silla (新羅). Later stories claim he was a holy Buddhist monk, although I don’t know if I’m aware of many monks at this point donning armor to visit royalty or suggesting that countries wipe out boats filled with men, women, and children.

(More as we get a chance to update)

-

Welcome to Sengoku Daimyo’s Chronicles of Japan. My name is Joshua and this is Episode 89: Baekje and Yamato on the Rocks

Last episode we covered the continued rise of Buddhism. From the enigmatic Prince Ohowake, and his importation of experts and texts to found a temple in the Naniwa region, to the more well-documented case of Soga no Umako, who continued his father’s efforts to establish a temple at their home in the Asuka area, going so far as to have three women inducted as nuns—the first clergy we know of to have been ordained in the archipelago, even though it may have been less than perfectly orthodox in the manner of ceremony. We also talked about how a coalition of other court nobles, led by the Mononobe family, were undermining the Soga and accused their new-fangled religious ideas of bringing plague to the people—plague that, even though the Soga’s temple was destroyed to prevent it, nonetheless took the life of the sovereign, Nunakura Fotadamashiki, aka Bidatsu Tennou.

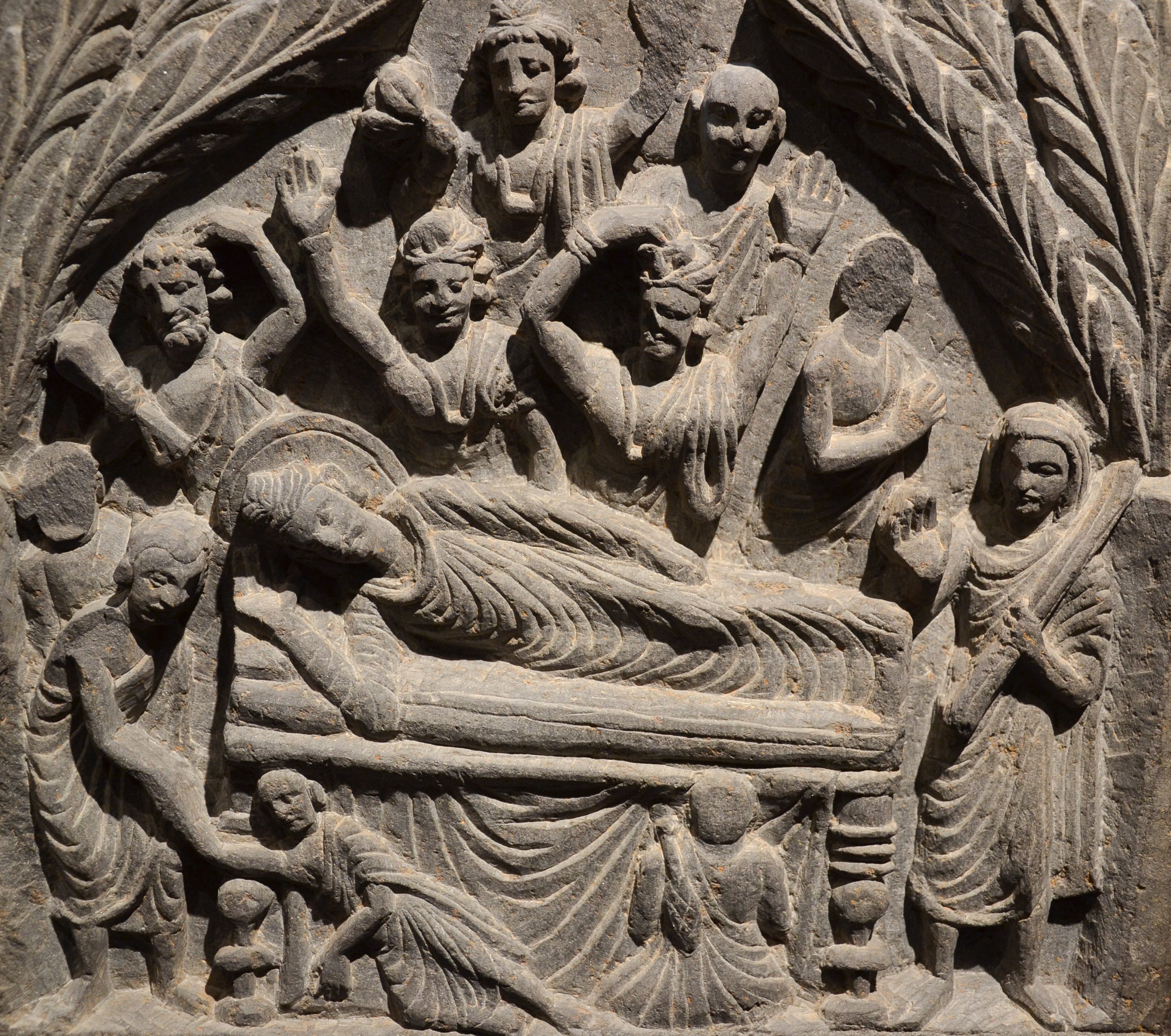

And for many, that’s probably the highlight of this reign, which was deeply involved in the spread of Buddhism, as well as providing the roots of the conflict between the old guard of the Mononobe and the newly risen Soga family. However, it isn’t as if that is all that was happening. There were continued international developments, among other things, and these were intertwined with everything else—nothing was happening in a vacuum. For example, the country of Baekje was the source of many of the early Buddhist texts and professionals, with Buddhist gifts becoming a part of the “tributary diplomacy” that is depicted in the Chronicles at this time. Whereas earlier diplomatic gifts may have included bronze mirrors, many embossed with figures such as the Queen Mother of the West, in the 6th century Buddhist icons and imagery seem to hold a similar currency.

I’d also note that giving Buddhist images and texts as gifts or tribute held an added layer of meaning, at least from a Buddhist interpretation. After all, not only were you providing prestige goods, which then helped boost the status of one’s diplomatic partners, but it also earned merit for the person gifting such things, as they were then able to make the claim that they were helping to spread the teachings of the Buddha. This provided an appeal to such gifts on multiple levels, both within and without the growing Buddhist world.

At the same time that Baekje and Yamato continued to advance their ties, Silla continued to grow. Since absorbing the states of Kara, or Gaya, including the Yamato-allied state of Nimna, Silla had grown and was consolidating its power. Silla itself had started out as a coalition of six city-state-like polities that came together in a union. They were one of the main targets of early Yamato aggressions on the Korean peninsula, with numerous discussions of raids by “Wa” sailors, though little is typically seen of the reverse. The Chronicles make the claim that early Silla was a subordinate tributary state of Yamato, which modern historians regard as little more than fiction—likely part of the propaganda campaign of the Yamato court attempting to place themselves in the superior position. Still, it does seem reasonable that prior to the 6th century Silla had remained a relatively minor state, occasionally allying with—or against—the states of Baekje and Goguryeo, as well as the other independent polities that were once present but have largely been obscured by the uncertain mists of the past. The fact that they survived as long as they did, and thus had so much written material, speaks to why they loom so much larger in the early histories, but such things are always hard to judge when all of your material basically comes from the quote-unquote “winners”, historically speaking. Just think how, if Kibi or Tsukushi, or even Izumo had become the dominant polity in Japan, our Chronicles would focus much more on what happened there rather than just covering what was happening in the Nara basin and adjacent Kawachi plain all the time.

And then there is the state of Goryeo, known to us today as Goguryeo, or Old Goreyo—in many ways the granddame of the Three Kingdoms of ancient Korea, with the greatest claim to the territory of ancient Gojoseon and Buyeo culture. Back in Episode 86 we saw a few of their attempts at diplomatic relations with Yamato landing along the Japan Sea side of Honshu—possibly a side effect of the path they were taking, sailing down along the eastern coast of the Korean peninsula, rather than via the Bohai Sea in the west. This may also have been indicative of the relatively friendly relations between Goguryeo and the expanding state of Silla.

Silla also offered up a normalization of relations, though it was met with mixed results—and even those mixed results are, well, mixed in terms of just what was really happening versus what was being projected back by Chroniclers writing a century or two later. Back in the previous reign, that of Ame Kunioshi, aka Kimmei Tennou, Silla envoys had also been received some time after their conquest of Nimna, and the Chronicles, at least, indicate that Yamato was less than enthusiastic to receive them, indicating that tensions remained high, and Ame Kunioshi took every opportunity to admonish Silla and to request that Nimna be reestablished as an independent entity, or so we are told.

Similarly, in the 11th month of 574, Silla sent another embassy, but we have very little information on it—given the timing it may have been intended to express their condolences on the death of Ame Kunioshi and their congratulations to Nunakura for ascending to the throne. About four months later, in 575, Baekje also sent an embassy, and we are told that this one sent more “tribute” than normal, possibly as a congratulations to Nunakura and an attempt to strengthen the Baekje-Yamato alliance. There may have also been a request for more specific assistance, since Nunakura apparently took the time to remind the Imperial Princes, as well as the new Oho-omi, Soga no Umako, to remain diligent regarding the matter of Nimna. As Aston translates it, he specifically said “Be not remiss in the matter of Imna”. Yamato was still apparently displeased with the fact that Nimna, which was once an ally, was now under Silla control.

Following that, the Yamato court sent their own envoys to Baekje and then Silla—though specifically they sent the embassy to Silla controlled Nimna, according to the Chronicles. A couple of months later, Silla sent an embassy back, including more tribute than normal, though the only hint of why, beyond the previous mention of Nimna, is that Silla was including tribute for four more townships, which seems kind of a weird flex, but may have been an indication of their growth, as well as a diplomatic notification that these four areas were part of what Silla now considered their territory.

The full reasons Baekje and Silla sent more tribute than normal are unclear; it could have been part of a recognition of Nunakura’s coronation and an attempt to butter up the new administration. It is possible that both Baekje and Silla were vying for Yamato favoritism, as well. Silla may also have been trying to basically pay off Yamato and get them to forget the whole thing with Nimna—something that, as we shall see, was not going to happen quickly.

Yamato sent another mission to Baekje in 577, two years later. This was the mission of Ohowake no Miko and Woguro no Kishi to Baekje, from which Ohowake brought back various accoutrements and set up a temple in Naniwa—modern Ohosaka. We discussed this, as well as our ignorance over the actual person of Ohowake no Miko, in our last episode, episode 88. It is interesting, however, if Ohowake no Miko was the actual individual who went to Baekje—mostly we see lower ranking men; those from Kishi level families, or similar. Occasionally a “muraji” or “omi” level family sends someone, particularly at the head of a military force, but not so often do we see a prince of the blood making the dangerous journey across the seas. I have to assume that this was an important mission, and that seems to have been borne out when you consider just what was brought back. Despite all of that, the details are frustratingly vague—worse than trying to find and put together the oldest episodes of Dr. Who and the First Doctor.

We do know that the whole trip took about six months, which gives a sense of what it meant to undertake one of these journeys. Most of that would have been living at the distant court. They didn’t have phones, let alone email, so they couldn’t really send word ahead with exact details—although there may have been informal communication networks via the many fishermen who regularly worked the straits. More likely, an embassy would simply show up in a boat one day and start asking the locals to “take me to your leader”.

Once you got there, they hopefully had room for you—they might even have a special location for you and your entourage to stay while they went through the formalities. After all, someone had to get you on the schedule, and any diplomatic gifts… ahem, “tribute”… should be catalogued and written down before the meeting. That way the host country could figure out just what they were going to reciprocate with. There is also possible training in any local ceremony and customs as you couldn’t assume that foreign dignitaries necessarily know what is expected. And then there would be the translating, likely through a shared language, possibly Sinic characters if everyone is literate.

Also, during that time, the mission would probably have been hosting guests or being invited out by some of the local elites. They were both guests and curiosities. And there might have been some personal trading and bartering going on off to the side—after all, you have to pay the bills somehow, and as long as nothing eclipsed the diplomatic mission, then I suspect there were some other “trade goods” that these ambassadors brought to help barter with locals and ensure they could bring back various goods and souvenirs.

In some cases, and it is unclear if it was by choice or not, ambassadors might be invited to stay longer, even settle down with a local wife and family. There are several examples of this that we see in the Chronicles, so it wasn’t all that rare.

So that was the mission from Yamato to Baekje. The next mission from Silla came in 579, some four years later, and we are told they brought “tribute” that included a Buddhist image. And then, only a year after that we have another mission, but it was dismissed before it could ever be received.

And that is a bit odd. Why would Yamato not receive the embassy? We aren’t given a reason, and it is pretty short, all things considered. We do know the names of the envoys. Indeed, the same two envoys: Ato Nama and Chilsyo Nama tried again two years later, but they were again dismissed, without accepting the tribute. This is all quite odd, but it does go to show the fickle nature of foreign relations.

One possibility may have to do with the way that “tribute diplomacy” appears to have worked. We know that in the case of the Han, Wei, and even the Tang and later dynasties, states were encouraged to come as tributaries, bringing goods as part of their diplomatic embassy, and then the receiving state was expected to provide items of even greater value in return. In the 16th century, various daimyo, or Japanese warlords, would use this to their advantage, representing themselves as legitimate emissaries in order to get the Ming dynasty court to give them even greater gifts in return. As multiple embassies showed up, all claiming to be the Japanese representatives, the Ming court started a policy of only accepting the first one that came, as they had no way to tell who was the legitimate ruler during the chaos of the Warring States period.

I bring that up because I notice that the first mission by Ato Nama and Chilsyo Nama took place only 8 months or so after the one in 579, which brought the Buddhist image. Given the typical time between embassies, that seems very short, and it seems quite possible that the Yamato court didn’t believe that the embassy was real, and that it was too soon after the previous one. Or it could even have been even more mundane—it is possible the court didn’t have the stores to pay out against the tribute, though that isn’t the reason that they would have given for turning them away. After all, it was not exactly a safe journey to cross the ocean and make your way to Japan. Whether you hopped down the island chain or took a more direct route, using the island of Okinoshima as a guide post in the middle of the strait, it was not particularly easy and many embassies never made it across or back.

I suspect, however, that there was something else going on, and that is in part because it seems to be the same two individuals coming back two years later, and they were once again turned away. It is possible that Nunakura and the Yamato court had a specific beef with these two individuals, but in that case they probably would have sent word to Silla to tell them to send someone else. This probably is indicative of the growing tensions between Yamato and Silla. From a narrative sense, it would make sense for Yamato to accept envoys just after a new sovereign came to power. It would help legitimize the sovereign, and it also offers a chance to reset and reestablish the relationship. The second envoy, bringing a Buddhist image, would certainly be something that the Chroniclers would find historically interesting and would bolster their own thoughts about the rising importance of Buddhism in the period. However, as we see in an episode from 583, Nunakura was still concerned about trying to re-establish Nimna. I suspect that this may have been a condition the Yamato court placed on Silla and the envoys, and it is possible that they weren’t willing to discuss anything without at least discussing that.

Or perhaps that is at least the impression the Chroniclers wish to give. They are still referring to it as “Mimana” or “Mimana no Nihonfu”, making claims that it was the Yamato government’s outpost on the peninsula, and therefore something of a personal blow to the Yamato court for it to have been overrun. Trying to re-establish Nimna would become something of a rallying cry; think of it like “Remember the Alamo” or “Remember the Maine”; regardless of the truth behind either incident, they were both used as justifications for war at the time. The case of Mimana was used to justify Yamato actions on the peninsula, and it would continue to be brought back up until modern times, including helping to justify Japan’s invasion of Korea in the early 20th century.

Here I’ll interject with the possibility that there could also have been some internal issues that the court was dealing with. Specifically, in between these two missions by Ato Nama and Chilsyo Nama, there was a bit of a disruption on the northeastern frontier, as the people known to the court as the Emishi rose up in rebellion. We aren’t given the details, but we are told that several thousand Emishi “showed hostility”. The Chronicle then claims that the sovereign simply summoned the leaders, including a chief named Ayakasu, who may have been a chief of chiefs, and then reamed them out, suggesting that he would put the leaders—i.e. Ayakasu and the other chieftains—to death. Of course, the rebellious chieftains immediately had a change of heart and pledged an oath to support Yamato.

Much more likely, I suspect, there was rising tension and hostility in the frontier regions, and Yamato likely had to raise a force to go face them. Assuming that was the case, it would have taken time to travel out there, subdue any uprising, and then drag the leaders back to the court to make of them an example to others. If that was the case, then it may have been that Yamato simply did not feel they had the time to deal with Ato Nama and his crew.

For a bit clearer reference, from the 8th through 11th years of the reign, there are simply relatively short entries. So in 579 there is the mission of ChilCheulchong Nama, who brought the Buddhist image. Then, in 580, we have Ato Nama and Chilsyo Nama attempt to offer tribute. Then, in 581, there is a rebellion of the Emishi, followed, in 582, by another attempt by Ato Nama and Chilsyo Nama to offer tribute. That’s about all that we have to go on.

In any case, though, we have a very clear indication in 583, only 9 months after again refusing the tribute from Ato Nama and crew, that Nimna was once again on the Court’s mind. Nunakura apparently went on a rant about how Silla had destroyed Nimna back in the days of his father, Ame Kunioshi. Nunakura claimed he wanted to continue his father’s work, but it was unclear just where to get started.

And so they decided to consult an expert. His name appears to have been something like Nichira—possibly something like Nila, depending on the pronunciation of the Sinic characters, or Illa in modern Korean, which is Aston’s preferred reading. It is said that he is the son of “Arishito” or “Arisateung”, the “Kuni no Miyatsuko”, or local ruler, of Ashikita, in the land of Hi, in Kyushu, and that he lived in Baekje, holding the rank of “Talsol”, the second official rank in the Baekje court. Ashikita was mentioned as far back as Episode 33, during the reign of Oho Tarashi Hiko, aka Keikou Tennou, as he was trying to subdue the Kumaso, and was likely a later addition to Yamato’s sphere of influence.

Nichira only makes a brief appearance here in the Nihon Shoki, but he is something of an enigma. He is presented as a citizen of Yamato, but his name appears to be from the Korean peninsula and even his father’s name hearkens back to another Arishito, who may have been the king of Kara or one of the associated polities. And yet here, this Arishito is the local ruler in Ashikita, in the land of Hi—later divided into Hizen and Higo. Given that he is referenced as “Hi no Ashikita no Kuni no Miyatsuko” this has been suggested as indicating that he was a member of the “Hi no Kimi”, the family that descended from the Lords of Hi. And this may connect to something later in the story.

There do appear to be some later documents that reference Nichira. Some claim that he was a Buddhist priest, and he’s even connected with the famous Shotoku Taishi in some stories, where he is depicted as a wise priest who recognizes Shotoku Taishi’s own Buddha nature. Of course, at this point, the prince would only have been about 10 years old, assuming the dates around his birth are at all accurate—a subject we’ll save for a later podcast, as there is just so much around Shotoku Taishi to cover.

As for the current story, however: Nichira was over in Baekje, at the court of the Baekje king, and so it wasn’t just a small matter of asking him to come to court. Ki no Kuni no Miyatsuko no Oshikatsu and Kibi no Amabe no Atahe no Hashima were sent on the dangerous mission of crossing the straits and bringing him back from Baekje. Their mission was for naught, however. Three months later they returned, empty-handed, with the unfortunate news that the king of Baekje had refused to let Nichira leave. Apparently his presence in Baekje was highly prized, and the Baekje king wasn’t willing to part with him so easily.

Yamato wasn’t deterred, however, and Nunakura sent Hashima back to Baekje. This time, Hashima went straight to Nichira’s house before any audiences at court. When he arrived, he heard a woman calling out in the local language a phrase which Aston found salty enough to throw into Latin: “Let your root enter my root!” Despite the implied sexual innuendo of such a statement, Hashima quickly understood what she meant and he followed her inside. She led him to Nichira, and there Hashima was asked to take a seat.

Nichira acknowledged that the Baekje king was not likely to let him go if he had a choice. The King was likely afraid that if Nichira went to Yamato then he’d never be allowed to return back to Baekje. Therefore, Hashima had to summon all of the authority vested in him by the sovereign of Yamato to demand Nichira’s release in no uncertain terms.

Sure enough, Hashima took the bold approach and demanded Nichira’s release, and the King of Baekje finally relented and allowed him to return. He wouldn’t go alone, however. Nichira was accompanied by other high officials from Baekje, including several men of the 3rd and 4th ranks, and a number of sailors to transport them.

They first arrived in the land of Kibi, Hashima’s own home base, and then headed on to Naniwa, where Nichira was greated by Ohotomo no Nukadeko no Muraji, likely a descendent of Ohotomo no Kanamura, the former top dog in the Yamato court. He offered Nichira condolences for the long trip he’d had to endure, and set him up in an official residence there in the port city.

Later there were daibu—high officials—who were sent to the residence to attend on Nichira.

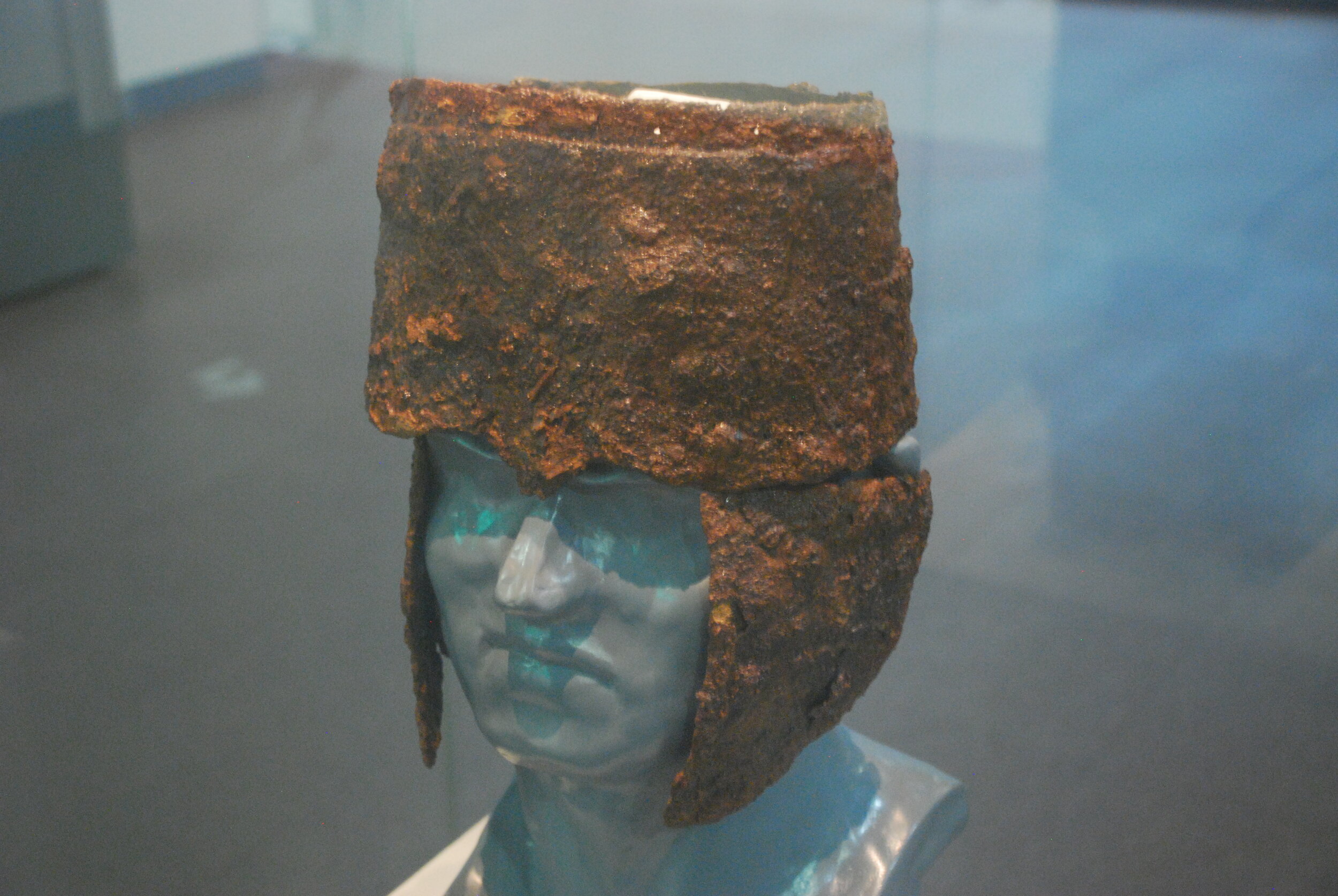

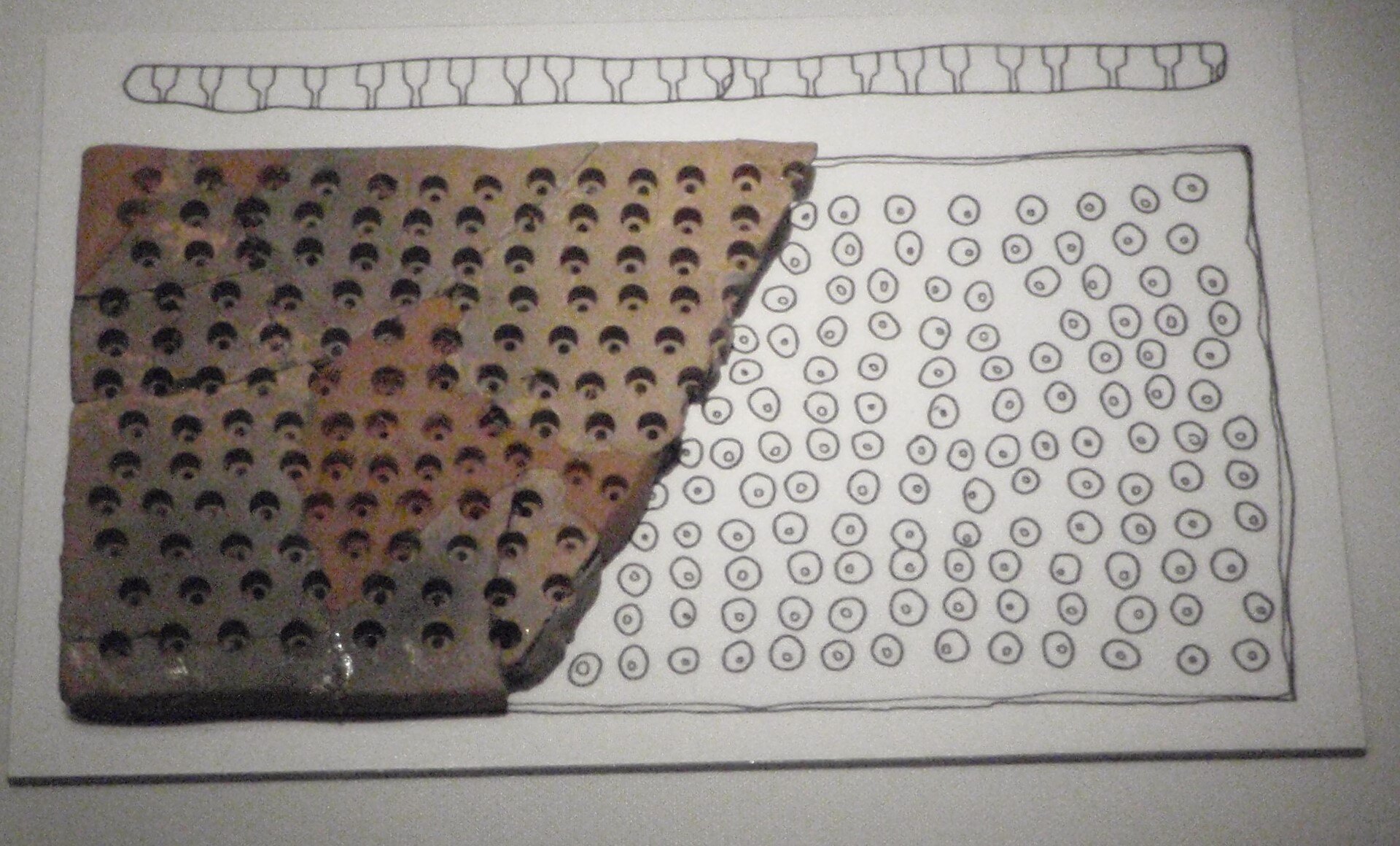

After he’d had time to freshen up, Nichira headed off to the court. When he drew near, he donned a suit of armor and mounted a horse, and in such a fashion he rode right up to the Audience Hall of the sovereign. There he bowed before kneeling down. He then recounted how his forefathers had been sent to the Korean Peninsula up in the first place back in the reign of Senka Tennou, aka Takewo Hiro Kunioshi Tate, in the early part of the 6th century. After explaining who he was and where he came from, he took off the armor and offered it as a gift to the sovereign himself.

Off to such a great start, the sovereign had a residence constructed for Nichira in the area of Kuwanoichi, in Ato—likely meaning an area of modern Ohosaka, near Naniwa. Later, with all of the ritual pleasantries out of the way, a war council was sent to ask Nichira just how they could move forward on the question of Nimna. This war council included Abe no Me no Omi, Mononobe no Niheko no Muraji, and Ohotomo no Nukadeko no Muraji.

Nichira provided them a plan to go to war, but it wasn’t simple nor was it quick. First he suggested that they spend the first three years building up the prosperity of Yamato, and getting all of the people behind the government. Next, he suggested building up a massive number of ships, such at that any visitors would be impressed to see them all in the harbor, and thus word would get out and it would project Yamato’s military power.

Finally, once that was done, Nichira suggested inviting the King of Baekje—or at least a royal representative in the form of a high prince or similar—be invited to Yamato, where they would see all of the power and good governance. They could then be taken to task for why Nimna had not yet been reestablished.

After the war council, Nichira sent a letter to the sovereign, Nunakura. In it he let Nunakura know that Baekje was going to send a request to relocate 300 ships worth of people to Tsukushi to settle there. Here things turned rather dark as Nichira suggested that they would see the ships filled with men, women, and children hoping to establish a Baekje colony in the archipelago. Nichira suggested setting up an ambush around Iki and Tsushima and that they should slaughter everyone. Then Yamato should build up fortifications of their own—probably as coastal defenses in case Baekje decided to retaliate.

And here I’m going to interject that this seems just really odd and strange. First, Nichira and Nunakura were talking about trying to reestablish Nimna with their ally, Baekje, and suddenly Nichira is suggesting that Baekje might try to establish a colony in their territory, and therefore it should be wiped out. That all feels very extreme, and this whole passage has puzzled commenters, especially when you consider the reputation Nichira later has as some kind of holy priest or monk.

Apparently this was the kind of advice, though, that may have been why Baekje did not want Nichira to come back in the first place. In fact, as the Baekje envoys themselves began to head out to return to Baekje, they left a couple of people in Yamato with a sinister plot of their own: as soon as the ships had sailed off and made considerable distance on the way back home, those left behind were to assassinate Nichira. In return, they were told that they would be given a higher rank and that their families would be looked after, in the very real possibility that they found out and killed themselves. A not insubstantial promise at the time.

With the official residence in Naniwa vacated after the departure of the rest of the Baekje delegation, Nichira decided to move back in, rather than staying in the home made for him in Kuwanoichi. The would-be assassins tried to approach him, and hatched plot after plot. However, they were stopped because apparently Nichira had some ancient superpowers. Indeed, his body apparently glowed brightly, like a flame of fire, and so the assassins could not get anywhere near him. They had to wait until the end of the 12th month, when Nichira’s own radiance faded, and they were then able to slay him.

This whole thing about radiance is intriguing, and may have several origins such that even if it isn’t factually accurate, it may have something more to say about just who Nichira was or might have been.

First off, there is the obvious. “Nichi”, in “Nichira”, means the “sun”, and so it could have been a direct allusion to Nichira’s name. This strikes me as also intriguing because the 12th month indicates the end of the year, usually meaning that it is darker. While the Winter Solstice would not have necessarily been in the old twelfth lunar month, those would have been the days when the suns light was least seen. Add to this that it was at the end of the month, and based on a lunar calendar, the end and beginning of the month would have been the times of the new moon, when it was not visible in the sky. And so we come to what most likely was the darkest night of the entire year.

There is also the fact that he is from Hi no Kuni—he is even considered a member of the ruling family of the land of Hi. The character of “Hi” in this instance is fire. Michaeol Como notes that the Hi no Kimi appear to have been associated with fire cults, as well as with rites of resurrection. “Hi no Kimi” could also be translated as “fire lord”. There may be some connection there with the story.

Finally, we can’t ignore the Buddhist context. Holy individuals are often said to radiate light from their bodies. For example, we have the story about Nichira meeting the young child that would be known as Shotoku Taishi, found in the Konjaku Monogatari, or “Tales of Now and Then”, a 12th century collection of various stories, many focused on Buddhist stories. In that story, Nichira radiates a light and the Shotoku radiates a light of his own in response. In fact, Buddhist images often depict holy figures with halos, or even wreathes of flames around them, likely a depiction or literal interpretation of what we find in the Buddhist texts, which may have originally been meant more metaphorically.

Oh, and notice how I talked about resurrection? Maybe you thought we’d just let that one slide. Well, apparently there was a brief zombie moment, as Nichira suddenly came back to life after he had been killed just to implicate the men from Baekje who had stayed back, and then he died again. Supposedly this is because there was a Silla envoy in port, and he didn’t want them to take the blame.

That resurrection piece, well, it isn’t the first time we’ve seen that, and it isn’t entirely uncommon to hear about something along those lines. In the Harima Fudoki there is another story of resurrection, and it involves a member of the “Hi no Kimi”, or lords of Hi. In that story, a member of the Hi no Kimi came to a center of Silla immigrants and married a young woman whom he had brought back from the dead. Another connection between the country of Hi and some of what we see attributed to Nichira.

At the same time, Saints in ancient England would occasionally rise from their deathbeds for one last piece of wisdom or to admonish someone before laying back down into that sleep of death. At the same time, it is possible that diagnosing death, versus, say, a coma or other unconscious state with very shallow breathing, wasn’t always a clear thing. In the west, as recently as at least Victorian times people were so afraid of being buried alive that there were tombstones created with bells that went to a pull down in the coffin, just in case. There have also been practices of pricking a corpse with a needle or similar to try to get a response. So I could believe that every once in a while a person who was declared deceased wasn’t quite ready to start pushing up daisies, and it is possible that this is more of a deathbed accusation than any kind of resurrection.

Still, the story clearly depicts it as a brief, but true resurrection. From his words, the court arrested the envoys who had remained behind and threw them into some kind of confinement while they figured out what to do with them. Nichira’s wife and children were moved to Kudaramura, or “Baekje Village”, in the area of Ishikawa, while the sailors who had been part of Nichira’s household were settled in nearby Ohotomo no mura. It is unclear if they were given leave to return to Baekje if they wanted, or if that was even on the table.

As for the murderers themselves, they weren’t punished by the Court. Rather the court handed them over to Nichira’s family, the Ashikita, for them to deliver justice. I believe this is the first time we’ve really seen this kind of justice in the Chronicles, with the familial groups taking such a direct role.

Now why is this story important, and what does it tell us?

Well, nominally, this says something about the continuing struggle by Yamato to reestablish Nimna, but I’m not sure how much of that is accurate. Though the story starts out about consulting Nichira about Nimna, there is nothing more to say on that topic, and it quickly becomes something that is almost more about the seemingly fragile Baekje-Yamato alliance.

There is also an interesting side note that through all of this there were apparently Silla emissaries there in Yamato, even though the Chronicle claims that the last two were sent away, so what’s up with that? It could be that the story is anachronistic—that is, it isn’t recorded in the right year. Or there was a mission that just didn’t rise to the level of being noticed by the Chroniclers. One other thought is that the formal diplomatic ties were only some of the traffic flowing back and forth. This seems the most likely, to me. By this point there was no doubt a desire for trade goods on both sides of the strait, and no matter where people came from, the merchant ships were likely plying the waters back and forth. So it is quite possible that the men of Silla who were in port were part of a trade mission, not necessarily diplomats.

Michael Como suggests some other reasons why this whole thing was considered important. He notes that there are several things here that connect this to the Abe family. It is unclear where this family comes from, but they have been mentioned here or there throughout the Chronicles, and by this point are at least are fairly high up in the court. Their name is a bit of an enigma for me, and I’ll have to do more research. I just want to note that they use a different “Be” than the Mononobe or similarly created corporate families. It is unclear to me why this would be the case, unless this is just where the two seem similar.

It should be noted that we should be careful not to assume too much about this early Abe family from one of its most famous Heian era descendants, Abe no Seimei, known as a famous Onmyoji, or master of Yin-Yang divination. I’m not entirely sure that the Abe were any more or less court ritualists than any other family, especially this early. Rather, it is their influence over certain geographic regions that is more immediately of interest.

We noted that as the son of a “Hi no Ashikita no Kuni no Miyatsuko”, Nichira was likely a member of the Hi no Kimi clan. They were originally based in southern Kyushu, and Como notes that they may have been under the sway of the Abe clan, at least by the 7th century, along with other notable families of Tsukushi, which is to say, modern Kyushu.

There are a lot of connections between Ashikita, Hi, and Silla that are telling. In the Harima story, it is a Silla wife that the Hi no Kimi marries. When Nichira resurrects, it is specifically to ensure that the Silla envoys who were present would not take the blame. Then there is his father’s name—or more likely title—of Arishito. A term seen used for the King of Nimna at one point, but also for the ancient Tsunoga, who is said to have been an ancient prince from the continent. Como suggests that Hi no Kuni—and thus their lords, the Hi no Kimi, may have played a part in the rebellion of Iwai, when Iwai attempted to ally Kyushu with Silla to break off contact between Yamato and Baekje. It is even possible that this was one of the reasons that Nichira was basically being held hostage in Baekje—perhaps he and his family had been exiled after the rebellion, or else left before any harm could come to them.

It would make some sense as to why the court sought him out in the first place. If he and his family were familiar with Silla, perhaps the court thought he would have particular insights. It might also suggest some of his motives regarding Baekje as well. Still, the picture is far from clear.

Although the Chronicle says that Nichira was taken back to Ashikita and buried, other sources suggest that he was entombed in Naniwa at Himejima, near Himegoso shrine. This, in turn, was the home of a sub-lineage of the Abe family, known as the Himegoso Abe. Como suggests that by the 7th century, the Abe were appropriating various Hi no Kimi cultic centers, to the point that by the time the Chronicles were written, the Abe no Omi and the Hi no Kimi were claiming common ancestry and jointly participating in various rites.

Como then links the timing of the death of Nichira to certain court rituals of fire pacification and purification. And so there may have been much more at play here than simply the story of Nimna and the attempts to reestablish that country.

As for the envoys who sailed off and left their lackeys to do their bidding? Apparently they were struck with a bout of karma on the way back, and their boat foundered and sank. This was likely seen as proof that their deeds had been committed with evil intent, at least by later readers, interpreting everything through a Buddhist lens that likely saw Nichira as more saintly than it seems he truly was.

After all of that, though, there is no evidence that the court really pulled it off. Instead, in 584, the year after everything had gone down with Nichira, the court sent Naniwa no Kishi no Kitahiko off to Nimna, now controlled by Silla, presumably to negotiate for some kind of reinstatement. That doesn’t appear to have happened, however, and the year after that, in 585, there was one more attempt, this time by Sakata no Mimiko no Miko. Sakata had previously been sent on a mission to request Silla reestablish Nimna in 571, only months before the sovereign, Ame Kunioshi, died. Now, as he was about to set out, the sovereign and the powerful Mononobe no Moriya came down with a pestilence, and were ridden with sores, such that they called off preparations for the mission. And sure enough, later that year, Ame Kunioshi’s successor, Nunakura Futadamashiki, likewise passed away.

I guess the rule here is don’t send Sakada no Mimiko to try to demand anything about Silla.

Of course, I have to also wonder if there wasn’t something else going on. It’s suspicious that the Chroniclers recorded two missions to Silla, both led by the same guy, both about reestablishing Nimna, and both happening just before the Sovereign passed away. Maybe history really repeated itself like this, or maybe the Chroniclers just knew that such a mission was sent in the last year of one of these reigns, and then put it in bothAnd we don’t hear anything more about Mimiko after that, either.

We also don’t hear anything else about the unfortunate envoy, Sakada no Mimiko, either. The other interesting thing to note is that, like Ohowake no Miko, Mimiko is a certified royal prince, though I don’t see any immediate name to connect him with, at least in the immediate lineage. It has been suggested that this is one of the sons of Wohodo no Ohokimi, aka Keitai Tennou, though even that feels tenuous to me.

Either way, both he and Nunakura, as we noted last episode, passed away from the disease sweeping the land.

And that concludes the reign of Nunakura. Next, we’ll get into what happened after his death as we start to see the Soga influence become pre-eminent. There is more to say about the growth of Buddhism and about the clash between the Soga and the Mononobe, one of the formative conflicts from this early period. And of course, we’ve already caught glimpses of Prince Umayado, aka Shotoku Taishi, who had quite the impact on the court—assuming he even existed. But that’s a discussion for another episode.

Until then, thank you for listening and for all of your support. If you like what we are doing, tell your friends and feel free to rate us wherever you listen to podcasts. If you feel the need to do more, and want to help us keep this going, we have information about how you can donate on Patreon or through our KoFi site, ko-fi.com/sengokudaimyo, or find the links over at our main website, SengokuDaimyo.com/Podcast, where we will have some more discussion on topics from this episode.

Also, feel free to Tweet at us at @SengokuPodcast, or reach out to our Sengoku Daimyo Facebook page. You can also email us at the.sengoku.daimyo@gmail.com.

And that’s all for now. Thank you again, and I’ll see you next episode on Sengoku Daimyo’s Chronicles of Japan.

References

Dykstra, Yoshiko Kurata (tr.) (2014). Buddhist Tales of India, China, and Japan: A Complete Translation of the Konjaku Monogatarishū. Japanese section. United States: Kanji Press. ISBN-978-0-91-788008-7

Como, Michael (2008). Shōtoku: Ethnicity, Ritual, and Violence in the Japanese Buddhist Tradition, ISBN 978-0-19-518861-5

Bentley, John. (2006). The Authenticity of Sendai Kuji Hongi: a New Examination of Texts, with a Translation and Commentary. ISBN-90-04-152253.

Aston, W. G. (1972). Nihongi, chronicles of Japan from the earliest times to A.D. 697. London: Allen & Unwin. ISBN0-80480984-4