Previous Episodes

- June 2025

- May 2025

- April 2025

- March 2025

- February 2025

- January 2025

- December 2024

- November 2024

- October 2024

- September 2024

- August 2024

- July 2024

- June 2024

- May 2024

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

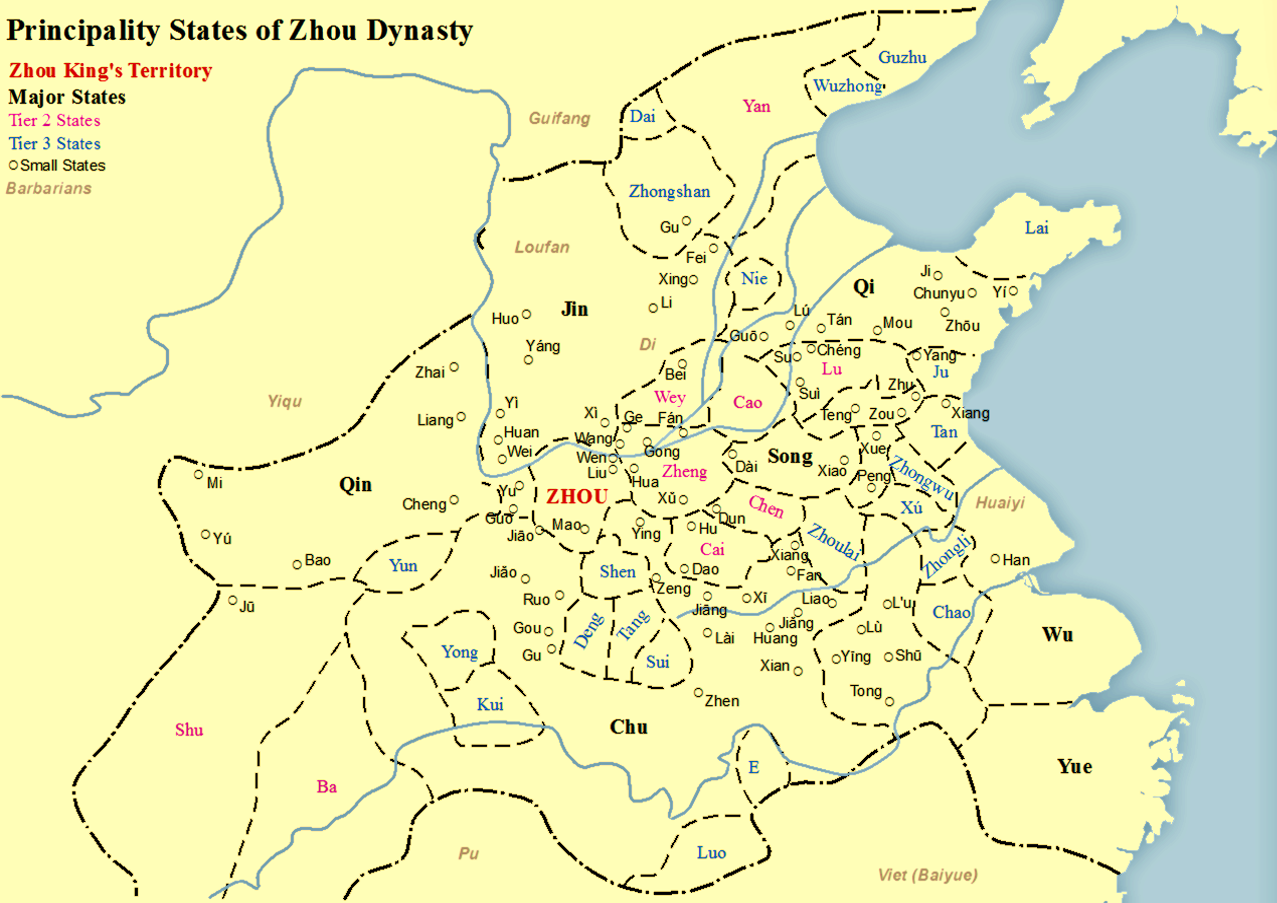

Welcome back! As we come out of the general turkey-and-stuffing-induced comas here in the US, we’ll be taking a break from the Japanese archipelago this episode and looking out across the water at what has been going on over on the mainland. We are especially going to be looking at the Yellow River Basin through to the Korean Peninsula. See the maps here for more context on the geographic settings in this particular episode.

Modern saddle crupper showing the position on the horse… well, I suspect you get the idea. Original image from Wikimedia Commons by Una Smith [CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)]

By the way, on the “Emperor Horse Crupper”, I should note that some English texts refer to him as “King”. This is probably a more accurate translation, though the term “Emperor” does show up in the dynastic names of this time. By some accounts “Emperor” really doesn’t apply until the Qin dynasty. There are similar arguments about the Japanese imperial line when we get there. Oh, and in case anyone is wondering what a “horse crupper” refers to (besides the name of the emperor), here is a helpful illustration, on the left. For those wondering, the character is 紂.

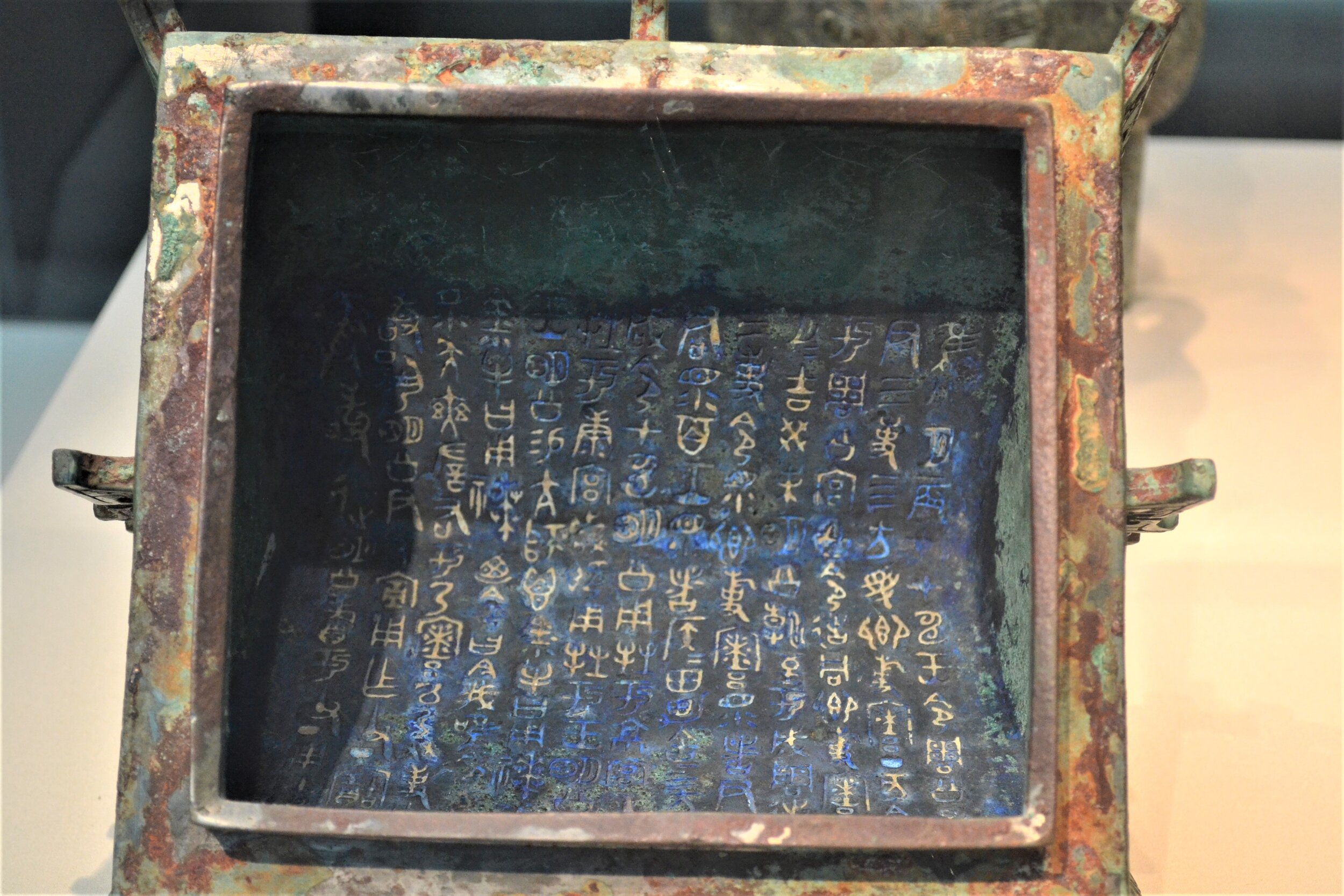

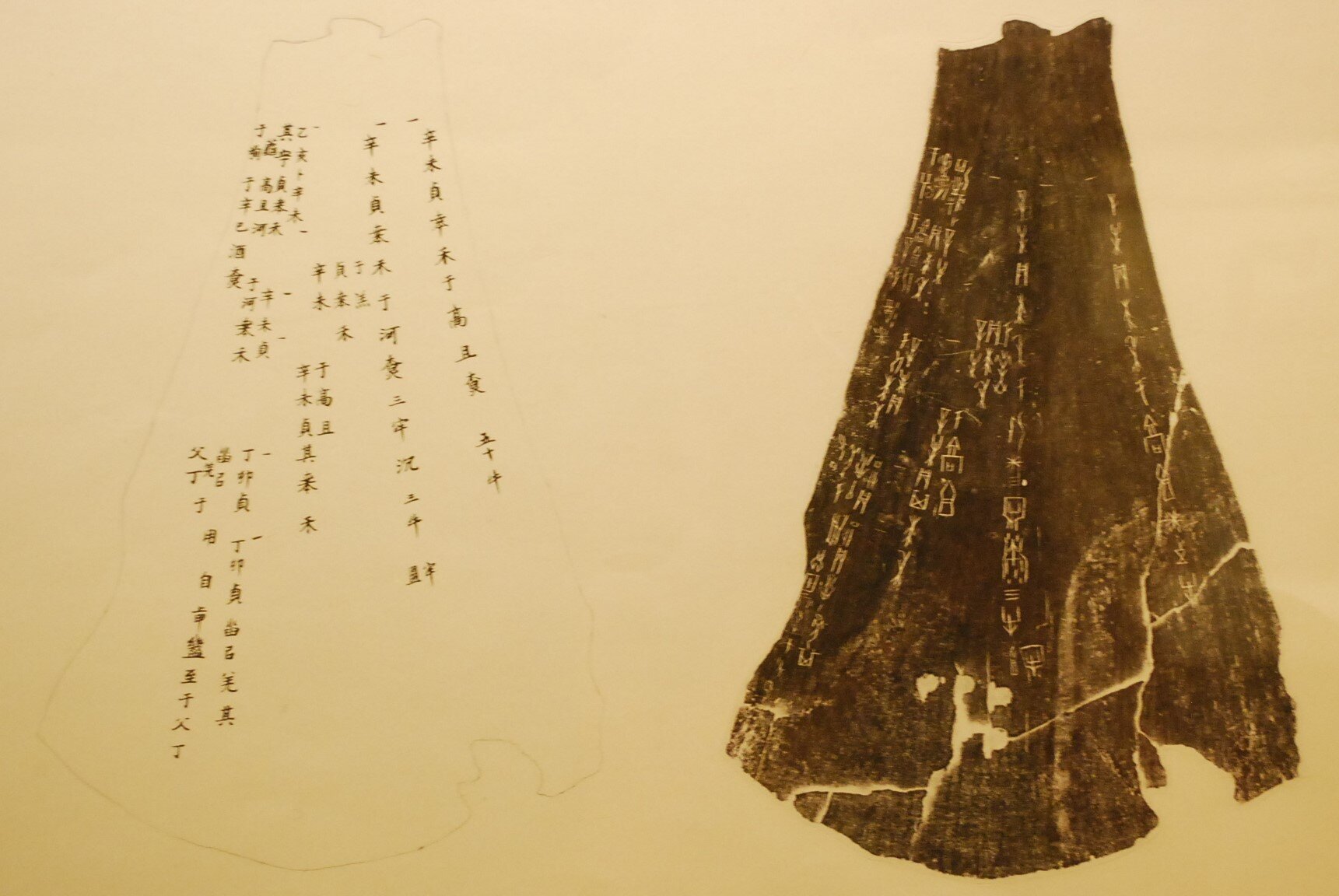

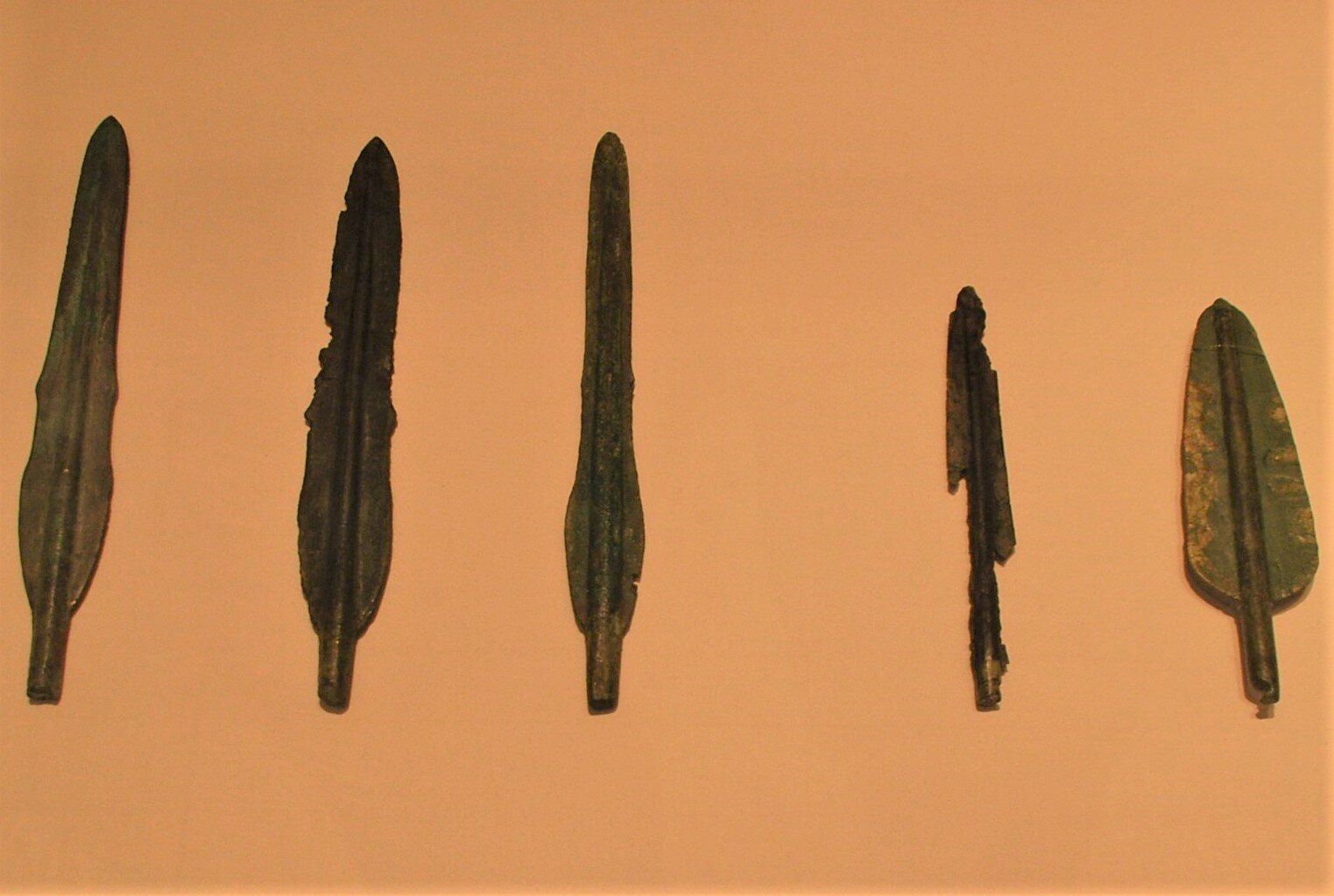

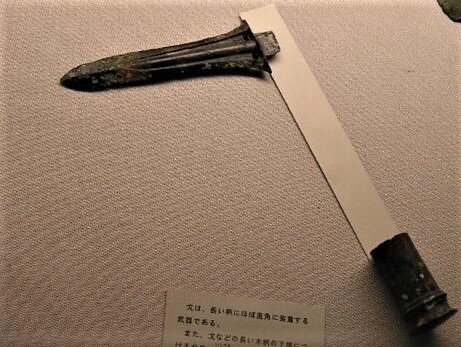

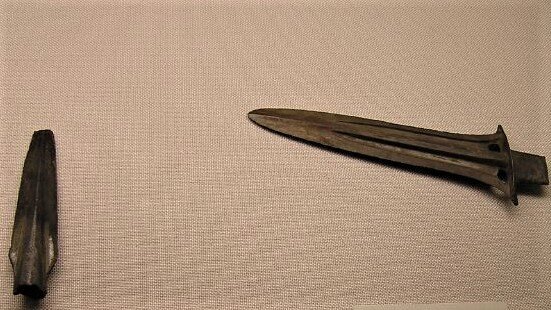

Finally, some examples of various bronzes and other artifacts from the continent between the Shang and Zhou Dynasty periods, including artifacts from the Korean bronze age.

References

2018 Li, Dora (trans.); “Two Ancient Chinese Stories: King Wen and King Wu”, Excerpt from Treasured Tales of China, trans. By Dora Li, https://www.theepochtimes.com/two-ancient-chinese-stories-king-wen-and-king-wu_2601618.html

2017 Barnes, Gina; Archaeology of East Asia: The Rise of Civilisation in China, Korea and Japan. Oxbow Books.

2015 Kim, Bumcheol; “Socioeconomic Development in the Bronze Age: Archaeological Understanding of the Transition from the Early to Middle Bronze Age, South Korea” https://scholarspace.manoa.hawaii.edu/bitstream/10125/55550/07_AP_54.1kim.pdf

2010 Ahn, Sung-Mo; “The emergence of rice agriculture in Korea: archaeobotanical perspectives” https://www.academia.edu/26244202/The_emergence_of_rice_agriculture_in_Korea_archaeobotanical_perspectives

2007 RHEE, S., AIKENS, C., CHOI, S., & RO, H. “Korean Contributions to Agriculture, Technology, and State Formation in Japan: Archaeology and History of an Epochal Thousand Years, 400 B.C.–A.D. 600”. Asian Perspectives, 46(2), 404-459. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/42928724

2004 Kim, Seong-hwan, ed.; Atlas of Korean History. History Education Department, Korean National University of Education; and Skyejul Publishing, Ltd.

2000 Theobald, Ulrich; China Knowledge.de – An Encyclopedia on Chinese History, Literature, and Art; http://www.chinaknowledge.de/History/Zhou/personszhouwenwang.html

1989 Fairbank-Reischauer; China: Tradition and Transformation (Revised Edition).