This episode we get to talk about one of the most intriguing and controversial parts of the Nihon Shoki and the Kojiki, and that is the claimed “conquest” of Korea, and as much as I’d like to just tell you the story, this time we really need to address the controversy, because it gets to the heart, in many ways, of modern relations between Japan and Korea. Before World War II, images of Empress Jingū were widespread, and stories about the conquest and subjugation of the Korean peninsula were used to justify Japan’s actions in occupying Korea in the early 20th century. After the war, there was a backlash against the nationalist version of history that had propped up such a view, with claims that Jingū never existed and she is simply a composite figure—the chroniclers knew that there were reaching the era when the Wei Chronicles said there was a Queen, and so they added a queen and then added on other stories, many of them actually coming from later female monarchs. In addition, they added details from the Baekje Chronicles, a no-longer-extant work that nonetheless seems to match up with what we have in later Korean histories.

Nonetheless, there seem to be enough details that I suspect there is at least a grain of truth to the story of Okinaga Tarashi Hime—I accept her as an historic figure—even if many other details have been glommed on to her story. Likewise, there is enough evidence that there were plenty of raids by the Wa (倭) on the Korean peninsula, though nothing firmly indicating subjugation of one of any of the Three Kingdoms. That said, it very well could be the case that Silla tried to “buy off” Yamato to get them to stop the raids, a tactic that we see time and again in various places in history. Without something like that, then how, exactly, do we explain the political hostages that were sent in the late 4th or early 5th century? Would Silla have sent a prince to Japan—especially without receiving a Japanese prince in return—unless they felt somehow compelled to do so? But we’ll get into that more in other episodes.

For this post, I want to try to lay out some of the things we talk about in the episode and give you some references you can check out. I am going to give you some of the dated references as well as more recent, so you can make up your own mind on some of these theories that people have put forth.

First, though, let’s talk about dates. For more in depth you can read our article on Calendar and Time.

The sexegneary cycle, starting with kinoe-ne (elder wood rat) and ending with mizunoto-i (younger water boar).

This was the kind of dating system that was frequently used throughout East Asia, in combination with the regnal names, creating eras and unique years within each era. However, it was likely not in use in Japan until the influx of actual writing. That leaves us with a problem: Although we can figure out the dates of things from outside annals, such as the Wei, Jin, Baekje, or Silla annals, we cannot necessarily trust the internal dates of the Japanese chronicles at this time, since by their own admission they had not yet started keeping written records in the continental fashion. Therefore it is entirely possible that the dates of things that are solely found in the Japanese records are out of place. It would be like having all the episodes from a highly episodic 80's cartoon show, without any of the names or show dates, and then being asked to put them together, in order. Now imagine doing that for, say, the 1940s Batman shows. You would be trying to use clues inside the episodes to put them together, but can you actually tell which order they are supposed to be in just by their content? Oh, and you' are probably missing at least half the shows. Good luck!

So we are pretty sure that things mentioned in the outside Chronicles happened, but they may have happened at different times. In this case they’ve combined the Wei chronicles, using the actual dates, with the Baekje Chronicles, but they’ve pulled that information back in time about 120 years—so that the cycle names still match up. The thing we aren’t sure of is whether all of the other action happening is properly dated. That is, is the rest of the story also 120 years out of synch, or is it inserted from somewhere else altogether?

We’ll talk about this more, later, but just to give you an idea of the confusion: The Nihon Shoki claims that Tarashi Hime lived through the reign of King Chogo (aka Geunchogo) of Baekje, and that he died before the end of her reign. On the other hand, the Kojiki has this same king interacting with Tarashi Hime’s son, Homuda Wake, during his reign, after Tarshi Hime had passed away. For what it’s worth, the Kūjiki seems to follow the dating of the Nihon Shoki, but doesn’t include the passages from other chronicles, sidestepping the question of dates altogether. So even though we are on the cusp of historical material—we will see writing arrive at the court in the next reign—we are still not sure of when, exactly, things are happening.

Still, we can use the dates we have in other sources to try to give ourselves some idea of what kind of intercourse is taking place between the archipelago and the peninsula. For instance, the Samguk Sagi gives the dates below as various points at which the Wa interacted with Silla or Baekje, prior to the late 4th century. While we cannot fully trust these dates, either—neither Silla nor Baekje seem to have kept written court records, themselves, until the mid-4th century—at least we can see what sorts of activity they were claiming. I suspect that these years are somewhat more spread out than they should be, and if that is the case we could be experiencing a kind of textual time dilation. Thus, assuming that these are at all accurate, these are probably accounts that took place within a span of a century or so, rather than the four centuries or so that is claimed:

50 BCE – Wa came with troops, intending to invade the coastal region of Silla, but withdrew because of the Founder Ancestor’s divine virtue.

20 BCE – Lord Ho, from Wa, was sent by the King of Silla on an official call to Mahan.

14 – The Wa sent more than a hundred ships to plunder the homes of the people on the sea coast.

59 – Silla established “good ties” with the Wa, and envoys were exchanged.

73 – Wa invaded the island of Mokchul. Kakkan Uo was sent to defend it, but to no success and he died there.

121 – Wa invaded the East Coast.

122 – A year later, a rumor that the Wa had come in “great numbers” caused people to hide in the mountains.

158 – Wa “courtesy visit” to Silla

173 – Samguk Sagi’s Silla Annals mention an envoy from Himiko. This feels way too early. She died in 238 CE. Some claim this is a highly anachronistic entry, and may reference a visit in 712 CE.

193 – The Wa had an epidemic and people came asking for food

208 – The Wa invaded the border [of Silla and the Six Districts]. Ibeolchan Ieum was sent against them.

249 – The Wa killed Seobulhan Uro

287 – The Wa raided Illye district and set it on fire. They captured 1,000 people and left with them

289 – The King, hearing that the Wa troops were approaching, repaired his ships and readied his armor and his troops.

292 – The Wa attacked and defeated Sado fortress

294 – The Wa troops came and attacked Changbong Fortress, but didn’t capture it.

295 – King of Silla suggested working with Baekje to attack the Wa across the sea, but his ministers suggested against it as they were not used to naval warfare and Baekje had often been deceitful.

300 – Silla exchanged envoys with the Wa

312 – The King of Wa sent an envoy proposing the marriage of his son. The court sent the daughter of Achan Geumri.

344 – The King of Wa sent an envoy requesting the marriage of the king’s daughter, but was refused because she was already married.

345 – The King of Wa sent an official letter severing ties.

Likely route for Yamato/Wa ships to the Silla capital at Gyeongju.

Late 4th century haniwa sculpture of a boat discovered at Takamawari Kofun No. 2 in modern Osaka. From the Osaka National Museum. Photo by author.

-

Welcome to Sengoku Daimyo’s Chronicles of Japan. My name is Joshua, and this is Episode 40: Tarashi Hime and The Conquest of Korea.

Sitting on a rocky beach, a fisherman mends his nets and sets his hooks, looking out into the ocean. The white-capped waves roll up and down, and mimic the whisps of clouds in an otherwise clear sky. Suddenly, there is a glint upon the water, a flash of light in the bright daytime in a time before electricity. Squinting his eyes, the fisherman can just make out the sight, but what he sees sends an immediate shiver down his spine. The glint of light is simply the sun, reflecting off of a polished bronze mirror, hung from the branches stuck into the prow of a long, low ship, which is cutting through the water at a tremendous pace, urged on by the practiced oarsmen who sit upon benches and propel it forward. Then, behind the lead ship, come more, appearing from around the cape and just over the horizon. The fisherman drops his work and runs back up to the village, screaming: The Wa are coming!

So last episode we talked about the rise of the Three Kingdoms, or Samguk, of the Korean Peninsula. This was Goguryeo, Baekje, and Silla. The fact that they seem to be keeping records from about the latter half of the 4th century is going to be key for helping us to understand the next part of the narrative. We also know that there are other groups operating on the Korean peninsula, though they don’t get the same kind of attention since they either weren’t keeping their own chronicles or, if they were, those chronicles don’t appear to be extant. Certainly the later Korean histories would focus on these three states, though there does seem to be some grey area as concerns the area known as Kara or, in modern Korean, Gaya. Either way, these three main kingdoms were definitely jockeying for position on the peninsula, playing a high-stakes game of warfare and international politicking that would eventually turn into a unified kingdom—though that is still some distance in the future.

Back in Japan, I want to just focus on the story as it is told from the Chronicles, at least for now. This is the idea that the Kami directed Tarashi Naka tsu Hiko to go and conquer Korea—specifically Silla—but he refused, remaining focused, instead, on the Kumaso of southern Kyushu. For his troubles, he was killed—whether in battle or by the mysterious power of the kami themselves—and so it fell to his Queen, Okinaga Tarashi Hime, as well as his prime minister, Takechi no Sukune, to carry out the kamis’ will and invade and conquer the Korean peninsula in the first place.

The Japanese Chronicles tell this as a fairly straightforward narrative, but with enough commonalities that there was clearly some source material available and common imagery that all of the chronicles are drawing from. The Kujiki even mentions a work that must have been around in the 8th century or so, titled “The Record of the Subjugation of the Three Han”, or “Seifuku Sankanki”, which may have been the original source from whence our story comes. Of course, even that source would be suspect, since it would still have been written down a good deal of time after the events that we are talking about here, which is still in the time of oral history.

So let’s get into it.

Now the Kojiki, as usual, is focused on the action and doesn’t sweat the small stuff. Remember, it was written down from what was effectively a performance piece by Hieda no Are, who would have recounted these stories for the court. As such, it launches straight into Tarashi Hime’s departure, stating: “She put the army in order and marshalled the ships.” Shortly thereafter she flew across the water, borne on the backs of every creature of the sea, and a giant wave brought the fleet halfway into the country of Silla—basically on the doorstep of the capital at Gyeongju. With no regard towards how they were going to get their boats back to the water—let alone all of the people who must have drowned in the flooding that such a tsunami would have brought with it, the Wa set up outside the Silla capital. The King of Silla, seeing such an overwhelming force, immediately capitulated, with no fighting at all. Next thing that you know, badda-bing, badda-boom, Tarashi Hime is planting her staff at the gates of Silla’s capital and Silla and Baekje are both sending tribute to Yamato. With Silla conquered, Tarashi Hime gets back in her boats (which probably had to be hauled back out to the ocean), and she’s sailing home.

Mission Accomplished. I’m sure that everything worked out fine.

Except that clearly there was much more to it than that. After all, when Tarashi Hime’s husband, the former sovereign, Naka tsu Hiko, died, the Yamato soldiers were still engaged with the Kumaso, and even if they wanted to obey the will of the kami they would need to disengage and regroup. Furthermore, they would need ships to take them across the straits in sufficient numbers to be effective. All of this is just glossed over in the Kojiki, but Tarashi Hime and Takechi no Sukune must have been working diligently to get everything ready.

Sure enough, in the Nihon Shoki, we see more of these details. Tarashi Hime first off puts Kamo no Wake, an ancestor of the Kibi no Omi, in charge of prosecuting the war against the Kumaso so she can attend to other matters. This he seems to take care of handily. But then, there were still a few out there defying Yamato authority, and Tarashi Hime didn’t want to leave to conquer the peninsula just to come back to some mess at home, and so she dealt with a few others before really heading out.

The first of these distractions is really fantastical. There was a fellow in a place called Notorita who was completely ignoring Yamato. He had a powerful frame, but more than that, he had wings. Yes, actual wings—at least according to the Chronicle, who names him as Hashiro Kumawashi, or “White-Feather Bear-Eagle”. I wonder if he was any relation to Chief Bear-Shark, that is: Kumawani? Anyway, this Bird Man of Notorita was apparently weighing on Tarashi Hime’s mind, so she went to Notorita and smote him. We aren’t exactly told how, but apparently she handled her business. And the proof of that? Well, there aren’t any birdmen flying around Japan today, are there?

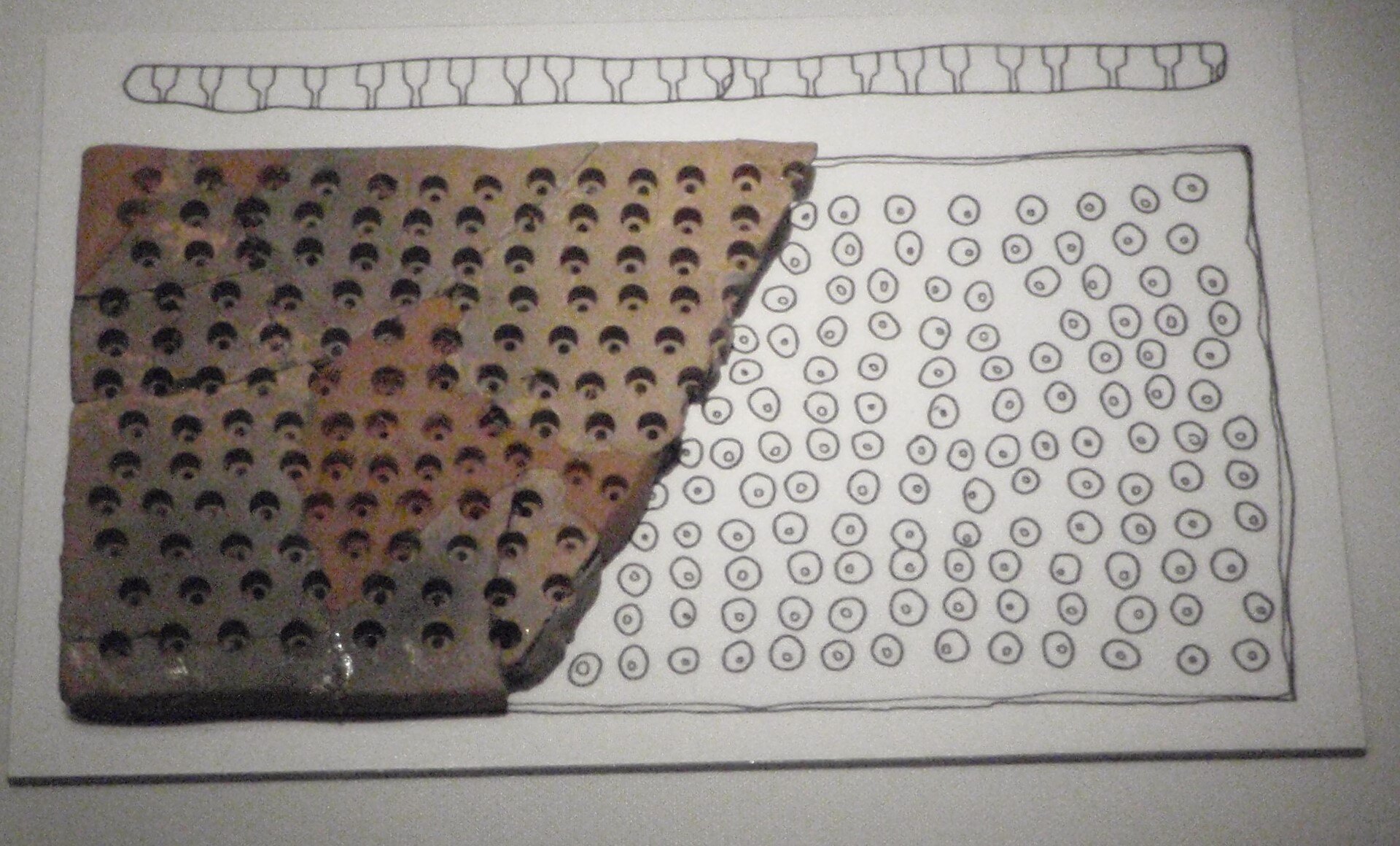

Seriously, though, this is where I’m probably supposed to mention that he was just a chieftain and perhaps there was some totemic thing going on with birds, and the whole thing got wildly out of control. There is an ancient form of wooden armor that some people have suggested was supposed to represent wings on the backs of a warrior, but I find that a bit of a stretch. Truth is, we don’t have any evidence to corroborate this, really, and this is the only source I know of for the tale.

Next up is the rather mundane story of Tarashi Hime defeating the Tsuchigumo in the Yamato district of Tsukushi—later Chikugo. It is said that she killed Tabura tsu Hime, and when Tabura tsu Hime’s older brother, Natsuha, heard about it, he scrapped his idea of raising an army against Tarashi Hime and decided to flee, which was probably the best course of action for him. Again, this is probably demonstrative of various fighting that was going on in the archipelago as part of the process—intentional or otherwise—to unite the islands under a single government, though clearly there was still plenty of independence. Assuming that others recognized Yamato’s hegemony it may have been something more like Primus Inter Pares—the first among equals—rather than a purely dictatorial authority.

By the way, I’m not sure why the Kami didn’t get on Tarashi Hime’s case for all of these apparent side quests. Wasn’t she supposed to go and subdue Korea? But, whatever. Who can say why the kami do one thing or another.

Regardless, it seems that Tarashi Hime was finally ready. Well, almost. This was a large undertaking, and one shouldn’t embark on such a campaign without a little divination to ensure that it would be victorious. Of course, this wasn’t some kind of scapulimancy or plastrimancy—that is, burning deer scapulae or turtle shells and reading the cracks. No, in this case, it took the form of several ukehi—the oath-style divination.

First up, Tarashi Hime put a piece of boiled rice on a hook and made the claim that if she was able to catch a fish then that would indicate that she would also achieve victory. Sure enough, as she cast her line into the Ogawa river in Matsura, on the western side of Kyushu, a fish bit the line and she pulled it up. Apparently this is something that was repeated by women in the area every year as part of a festival, commemorating the event.

Next, Tarashi Hime set aside a sacred rice field and tilled it in anticipation of victory. She had an irrigation channel dug all the way to the Hill of Todoroki, where she planned to divert water from the Nakagawa river. However, the engineering crew encountered a seemingly insurmountable obstacle when they ran into a giant boulder. Tarashi Hime, the sovereign who had smote the mighty birdman of Notorita—and, fair warning, I’m probably going to just keep bringing that up—was not concerned. She had Takechi no Sukune pray to the kami of Heaven and Earth while she presented a mirror and a sword as offerings. Sure enough, out of the sky came a bolt of lightning that split the rock asunder, allowing the water to flow through. This was known as the Sakuta Channel.

Finally, at the Bay of Kashihi, Tarashi Hime got into the water and made the prediction that if the campaign would be a success, her hair would naturally part in two. Sure enough, as she lay down in the water the currents naturally took her hair and split it into two, which she then tied up in the fashion of a man—in fact, the Chronicles claim that she purposely donned the outfit of a man at this point in order to lead men into battle. Of course, that could just be the Chroniclers borrowing from some Chinese stories to help make things that more epic for their readers, or it could be the fact that, other than perhaps where it sits on the hips, armor doesn’t really care that much about how your body looks, let alone what pronouns you use, and generally provides everyone the same basic profile.

So kitted out in her armor, and with all of the omens pointing to “yes, do this thing already,” do you think Tarashi Hime was ready?

Of course not.

Apparently, despite everything else, they were having trouble raising enough ships for the voyage. And having an army is all well and good, but if you don’t have ships, well, that’s an awfully long way to swim. Of course, as with many things during this period, the answer isn’t just “build more ships”, but rather to address the real problem: Figuring out which kami you need to properly appease. In this case it was the kami of Ohomiwa, who perhaps hadn’t been feeling much love since the sovereigns had largely buggered off to everywhere *except* Yamato, recently. Tarashi Hime offered Ohomiwa no Kami a sword and a spear, and that seems to have done the trick. With Ohomiwa’s divine blessing they were able to raise the ships and the men and get things underway.

Except for one other thing. You may recall that the Kami who were spiritually financing this conquest had killed Tarashi Naka tsu Hiko, but had then said that the lands of the Korean peninsula would be given to the unborn child in Tarashi Hime’s womb. That’s right, Tarashi Hime wasn’t just going about all of this in the moment of her grief, she was also doing it while *pregnant*. However, she had no time to be giving birth—she had land to go and conquer. And so she performed a ritual where she attached two white rocks around her waist—some even say in her nether regions—and made another ukehi, praying: “let my delivery be in this land on the day that I return and our enterprise is at an end.”

Apparently those two stones were then set beside the road in Ito, where people would worship at them as they passed by. They were eventually stolen, but there are plenty of references to their miraculous power. These weren’t small stones, either—they were apparently about one to two shaku in length—so about half a meter or so.

Anyway, whew, finally! All of the prayers and divinations had been made, all of the ships and men were gathered, and Tarashi Hime’s pregnancy was put on a supernatural pause. It was time to go out and see what they could find.

The exact route of the journey isn’t mentioned, but it isn’t hard to guess just where they went, hopping from island to island until they got to Tsushima, and they departed from the bay of Wani for the territory of Silla. The Nihon Shoki, just as in the Kojiki, claims that the Yamato ships were borne on the backs of the fish and beasts of the sea, and they were aided by the Sea-god and the Wind-god—though the phrasing of the latter looks more like a Chinese phrase than something from Japan. As with the Kojiki, they were carried halfway into the territory of Silla, catching their prey largely unawares. When the King of Silla saw this, he immediately capitulated, waving a white flag, which is apparently a universal signal. Then he came out of the gates with his hands tied behind his back in a form of submission, just as we saw the Emishi chiefs do when they surrendered to Yamato Takeru. Tarashi Hime graciously accepted his surrender and made the King of Silla into her “forage provider”—basically the position of a lowly servant.

Now with such an entrance, word got around the peninsula, and Baekje and Goguryeo, the other two major powers at the time, sent spies to check out the Yamato army. They were so impressed by its size that they decided not to fight. Instead, they submitted to Yamato and agreed to send tribute of their own.

With things well in hand, Tarashi Hime headed back to Japan in triumph.

And that’s it, that’s the conquest of Korea. Except, well… maybe not? Let’s see if we can get past the story and into what may have been actually happening.

Now I have both been looking forward to and dreading getting into all of this here and the next few episodes. I’ve been looking forward to them because they cover an extremely dynamic part of the Chronicles and the history of the archipelago, and there is some actual documentation to attach it to on the peninsula. In fact, from here on out we’ll be getting into what we can reliably call the “historical” period for Japan, as they’ll soon start keeping their own records. On the other hand, as we make the transition from oral to written history, the boundary zone is rather like two rivers coming together, and occasionally the eddies and whirlpools of the narrative may bring us forward or backwards in time, so we get events verified by other sources, but well outside of their appropriate period. This leaves us with a quandary or two. For my part, I’ll try to keep the 4th and 5th century chronology consistent with what we know from continental sources, and then I’m using a bit of shorthand to otherwise line up events here. You see, in the reigns of Okinaga Tarashi Hime and her son, Homuda Wake, we often have direct quotes from mainland sources. The Chinese quotes are from the Weizhi, and these are clearly referencing Himiko—which I would argue could not be Tarashi Hime. However, because the chroniclers were trying to add years to the royal lineage, Tarashi Hime’s reign is given as probably about a century and a half too early—they are claiming dates that correspond to about 200-269, but describing events that seem much more likely to have been occurring from about 340-375 CE. In fact, the entries that correspond with known events in the Korean annals—particularly those of the country of Baekje—appear to correlate by exactly 120 years.

Now we won’t get into all the complexities of ancient Asian dating systems here—I’ll leave that for the blogpost—but suffice it to say that there was a 60 year, or sexagenary, cycle. It was actually 5 cycles of 12. Every series of 12 corresponds with one of the 12 zodiac animals you see on the placemat at many Chinese restaurants, and then each of those was paired with the five elements: Fire, Earth, Metal, Water, and Wood. In total, this creates 60 unique year designations. These were used with the name of the reigning monarch to determine what year it was, and together they create a means of recording what happened in what years of any given reign. Once you know the reign orders and lengths, you should be able to correlate them to an absolute date. What the Chroniclers have done is added two cycles of 60 into their calculations somewhere, so that they are placing the events from the Baekje sources in the correct place to match up with that 60 year cycle, but just two cycles too early. Eventually those will start to marry up over the next series of reigns.

By the way, we do have at least two other pieces of corroborating evidence for this period. The first is a large stone pillar, or stele, known as the Gwaangaetto Stele, and it tells the story of the reign of King Gwangaetto the Great of Goguryeo. It is notable because it was erected in the 5th century, not long after the events that it records, but most of the events described occured at the very tail end of the 4th century and early into the 5th. The other piece of evidence that we have is a strange, seven-branched sword, which appears to have been given to the Japanese sovereign by the country of Baekje and it has an actual date in the inscription. This will come into play as we try to assess what is happening when. Unfortunately, none of these artifacts really give us the names of the Yamato sovereigns, so while we can verify that the events took place, who was actually on the throne is still a bit of an issue.

There is one more thing that we should pull out into the open here, and that’s the controversy surrounding this whole story. Nationalist scholars in pre-war Japan took it as a given that this story proved, conclusively, that Japan had subjugated Korea and therefore were justified in reasserting their control over the peninsula in modern times. Furthermore, when Japan occupied Korea in the early 20th century, and while they were propping up the puppet state of Manchu-kuo, many nationalist scholars used the Gwangaetto stele—which has numerous mentions of the Wa fighting on the peninsula—as evidence that Yamato was a major player in peninsular politics. On the flip side of this, many of the characters have been worn down with time and are illegible, and there are accusations against the Japanese army that they enhanced the inscription so that it would read more favorably based on their interpretations. While other, independent scholars have attested to the authenticity of the inscription as it is generally known, there are still different interpretations over exactly what it says, given the still missing characters. Still, it is a valuable resource given its proximity to the events in question.

To many of the pre-war Japanese scholars, the events of Tarashi Hime’s reign culminated not only in the subjugation of the peninsula, but in the establishment of a Yamato colony, known in Japanese as Mimana—or Imna in modern Korean. This was effectively treated as known fact, and knowledge of Tarashi Hime by her posthumous name: “Jinguu Kougou” was fairly well known. That said, the actual location and even existence of Mimana-slash-Imna has been hotly contested on all sides. However, I want to leave it off to the side for the time being. After all, nowhere in the narrative on Tarashi Hime’s conquest have we yet mentioned “Mimana”, and though various scholars have attempted to situate it in these earliest stories, it just isn’t clearly there, yet. That’s not to say that there wasn’t some place called Mimana, or Imna, or perhaps more appropriately “Nimna”, the contemporary Chinese reading for the character. The name even shows up on the Gwangaetto Stele, but if such a place as Nimna did exist, we don’t have any record of exactly where it was, nor what their leadership, culture, or ethnicity may have looked like. Many equate it with the polity in Gimhae known as Geumgwan Gaya [check spelling and pronunciation!], but even that seems to be conjecture at this point and not confirmed fact..

Of course, many scholars—especially Korean scholars—have pushed back against this interpretation of events. They claim that Japan never conquered anything, though they may have raided the coast quite a bit—especially the coast of Silla. Also, it is unclear whether or not the “Wa” mentioned in those ancient accounts had anything to do with the polity in Yamato in the archipelago. Were they armies sent by a strong central government? Or were they raiding parties from individual groups—most likely in Kyushu or even on the peninsula itself—who were operating independent of any larger state system? I wonder if it wasn’t a little bit of both, but I’ll talk about that in a bit.

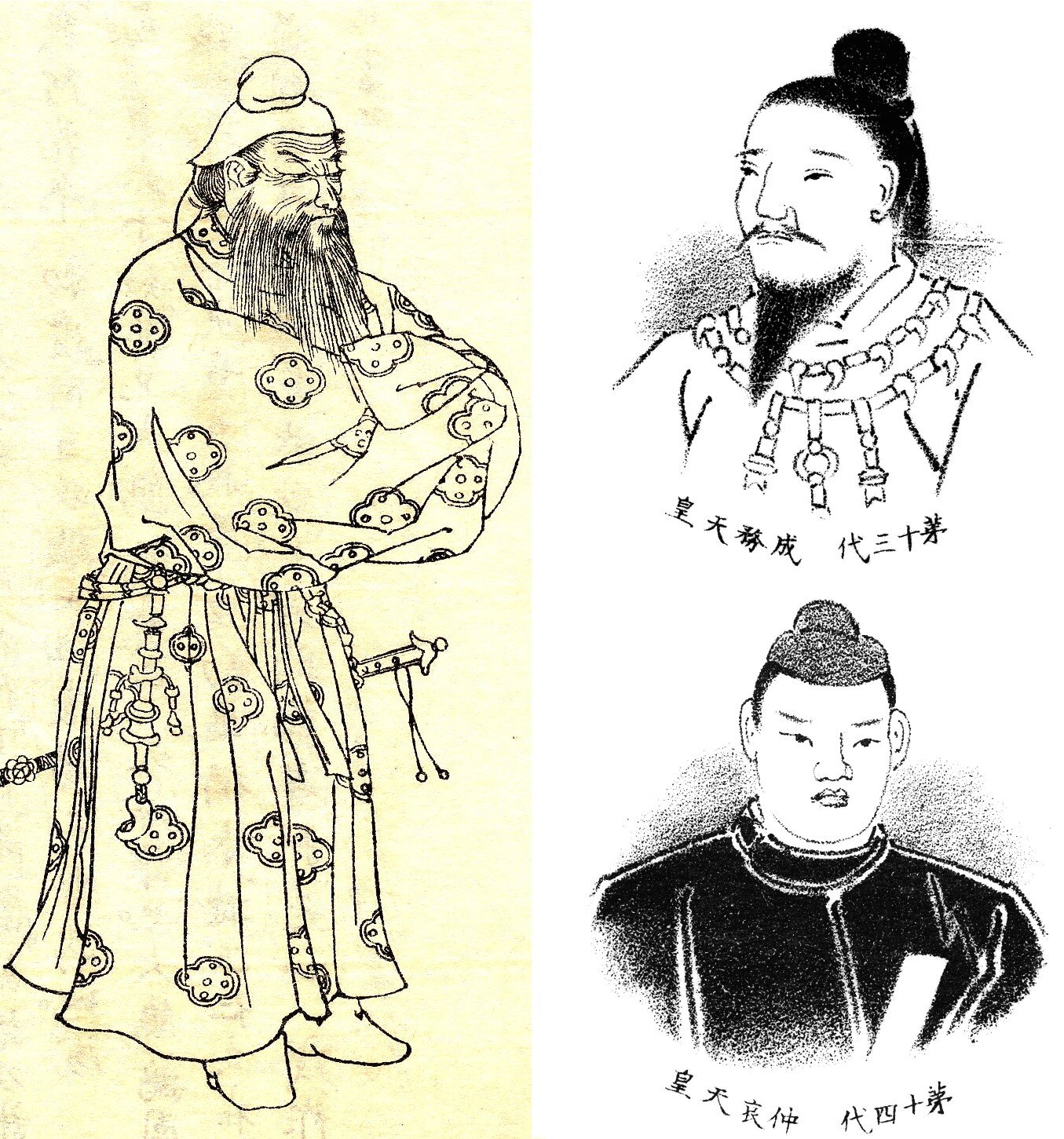

There was also a push by Japanese scholars to reexamine the Chronicles. In the pre-war period, even the suggestion that there were problems with the official imperial genealogy could bring accusations of lese majeste and there were actual trials early on. This brought on a backlash as some scholars claimed that everything from Jimmu to Oujin—or in our case, Iware Biko to Homuda Wake—was a fiction created by the court to prop up the Yamato royal lineage. Because of the dates in the Nihon Shoki, and the Wei Chronicles talking about an early 3rd century female ruler in Japan, the Chroniclers somehow had to fit Tarashi Hime into the narrative. And so she is given credit for the work of Himiko, but they also layered on the various stories of attacks on the Korean peninsula and the birth and ascension of Homuda Wake. There is even the belief that some of the stories should be attributed to much later female sovereigns. Now, I think by now you know where I stand on this—somewhere generally in the middle—but just know that there are still some people who believe that Tarashi Hime herself is entirely fictional.

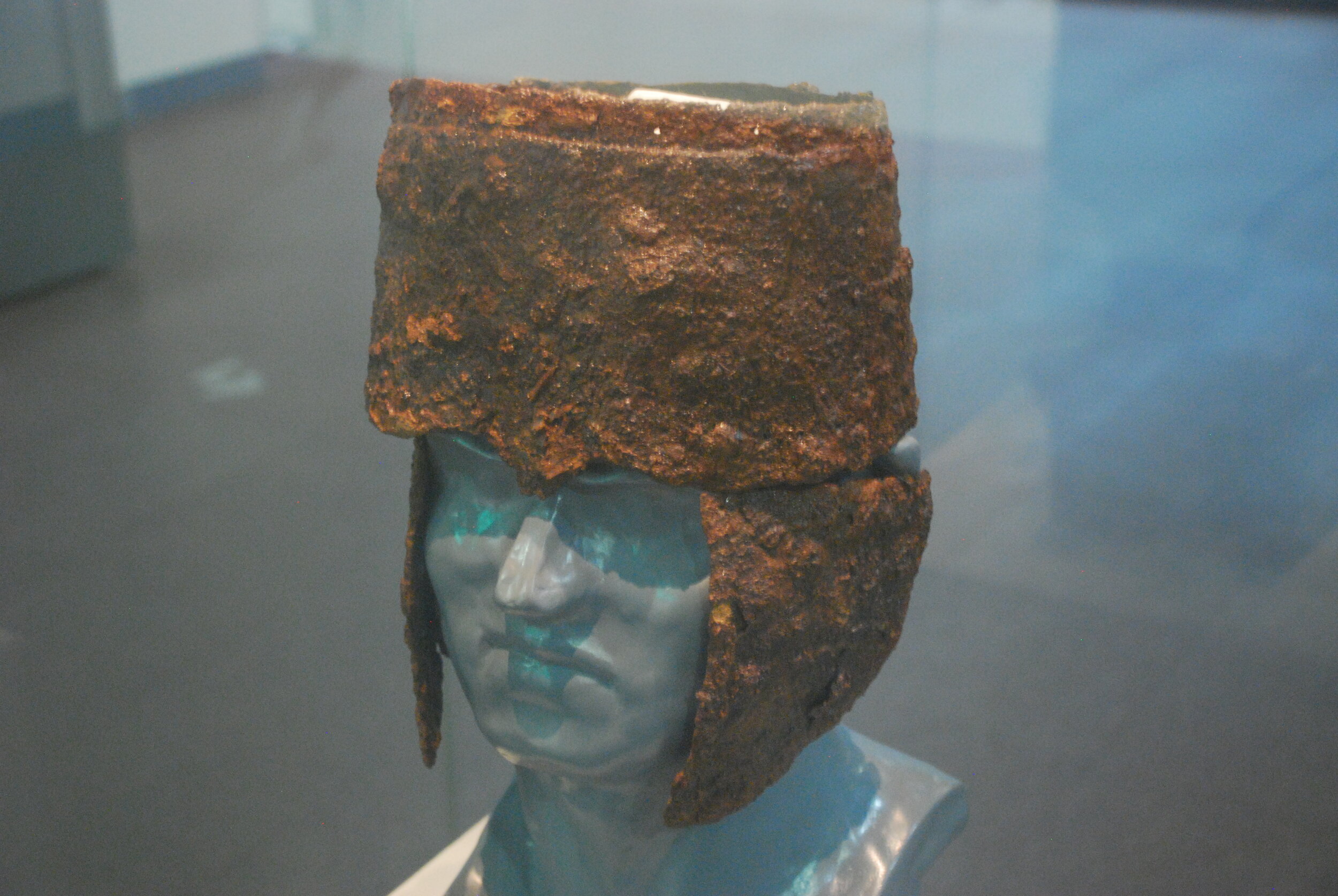

And then there is one other area that I want to address, which completely turns all of this on its head. This is the idea that the story of the conquest of Korea is actually *backwards*. It isn’t the story of Yamato conquering Silla, but rather the story of Baekje conquering Yamato. Yes, you heard that correctly. This theory holds that Tarashi Hime—if she existed—as well as Tarashi Nakatsu Hiko were actually from the continent. Eventually Tarashi Hime fought her way to Japan and all the way to Yamato where she put her son, Homuda Wake, on the throne. According to this theory, later Japanese sovereigns reversed things and added this story about the conquest to cover up their own lineage as Baekje nobles. This usually goes hand-in-hand with the “horse-rider” theory of Egami Namio, formulated around 1949, and later supported by Gari Ledyard in a paper in 1975. Namio’s theory points to the lack of horse-riding gear in the early archaeological record, up through the 4th century, and then its sudden explosion across the peninsula in the 5th century, and suggests that this was because Buyeo nobles from Baekje had arrived with their cavalry and these horse-riders had easily defeated the unmounted soldiers of Yamato. This theory has largely been denounced—in large part due to the archaeological evidence—but it still has some adherents.

As you can see, and as we’ve discussed previously, interpretations of the past can be influenced by modern thoughts and opinions, so let’s try to be aware of our own as we approach the material. I know this was long and involved, but I think it is necessary to really dig into some of this stuff.

Personally, as I mentioned, I find at least a grain of truth in most of these perspectives. Is Tarashi Hime completely mythical? I don’t know that I’m prepared to go that far, but clearly a lot of what is attributed to her is either anachronistic or clearly belongs to someone else’s story. There is also the fantastical nature of many of her exploits, even moreso than Yamato Takeru in places—and he was fighting off gods left and right. So I think we can tone down the rhetoric a bit, but that doesn’t mean she was not some sort of historical personage, or at least representing some person that was important enough to be remembered. So we’ll try to untangle a bit of what we know, but we can only go with the information presented to us.

Let’s start with the so-called invasion of Korea, which is really at the crux of what makes Tarashi Hime so controversial, given Japan’s later actions on the peninsula, including the invasion by Hideyoshi and the occupation in the early 20th century. One would think that such a massive undertaking as conquest of the peninsula would have found its way into the Korean records. Now, Aston was regularly checking his translation of the Nihon Shoki against the Dongguk Tonggam, a 16th century history of Korea that pulled together various other accounts, and I’ve also been checking against English translations of the Samguk Sagi and the Samguk Yusa, specifically the Silla, Baekje, and Goguryeo annals. None of them has anything that comes close to the scale of assault that we could really refer to as subjugation, or even direct Yamato control of anything on the peninsula at all.

The Korean histories, especially the Silla Annals, have contact with the Wa people noted as far back as 50 BCE. Of course, I have a hard time accepting that, since that is a mythical time even for the Korean histories, where founders are being born out of eggs and that sort of thing. Still, let’s take a look at the references and see what we find, realizing the dates are probably a little out of whack, at least until we get into the mid-4th century.

In Silla’s early history we see a Lord Ho serving the king who was originally from Wa. This in the time of Mahan, the confederacy that was eventually subsumed by the Kingdom of Baekje,

Early on, Wa sent 100 ships to plunder the homes of people on the eastern sea coast. Later, Silla established good ties with the Wa, but it wasn’t too long until the Wa invaded the island of Mokchul. Silla sent someone to defend the islands, but to no avail, and their general was killed. Then, the Wa came back and invaded the East Coast with such ferocity that only a year later there was a rumor that the Wa had returned in quote-unquote “great numbers”, causing people to abandon their villages and hide up in the mountains until they realized it was just a rumor.

Some time after all of that, Wa sent a “courtesy visit” to Silla. Later they claim that in 173 the Silla king entertained an envoy from Himiko. This entry is suspect—it seems to make an assumption based on the Weizhi and possibly using a later envoy from the Japanese court in 712. It is clear that, even though the early sources they were drawing from may have been referencing different polities all as “Wa”, by the time the Samguk Sagi was put together the Chroniclers just assumed that all of these were from the Kingdom of Yamato, generally accepting Japan’s own claims to an ancient state.

The entry for 193 is interesting in that it mentions refugees from Wa coming to ask for food because of some kind of epidemic. I’m reminded of the epidemic during the time of Mimaki Iribiko, but it isn’t clear that the two are actually related. Of course, a little more than a decade later the Wa are invading the borders of Silla and the Six Districts—which likely references the six communities that came together to form ancient Silla. Silla sent a general against them and he seems to have been successful.

In 232, it is said that the Wa “unexpectedly” showed up, surrounding the Silla capital at Gyeongju. The king personally went to fight them, and they scattered. Silla sent cavalry to pursue them, capturing a thousand of their troops. It apparently did not stop the Wa from attacking, though, as they would invade and raid the eastern coast the following year until Silla fought them at a place called Sado, setting fire to their ships.

Then, in 287, the Silla annals claim the Wa raided Illye district and set it on fire, capturing a thousand people and taking them with them—probably as slaves, given what we have seen in similar conflicts.

In 292, the Wa attacked and defeated Sado fortress, where they had previously been defeated, and two years later they attacked Changbong fortress, though they were unable to capture it.

In 295, apparently fed up with the raiding by the Wa, the King of Silla suggested working with Baekje to attack the Wa across the sea, but his ministers suggested against it. For one thing, they didn’t feel they could trust Baekje to hold up their end of the bargain, as Baekje had proven themselves deceitful many times over, at least from the Silla point of view. Furthermore, Silla didn’t really have a navy and they weren’t used to naval warfare, unlike the Wa, who seem to have been masters at it. This really sounds like the Wa really owned the sea lanes, early on. Those tables would be turned centuries later, but not right now. This may be why, five years later, Silla agreed to exchange envoys with the Wa, to try to find peace and put a stop to the raids. Indeed, in 312, the Silla Annals claim that Wa even sent an envoy proposing marriage to one of the King’s sons. The court responded by sending a noblewoman, the daughter of a man of the rank of Achan named Geumri. Thirty years later, the King of Wa supposedly requested the hand of the King of Silla’s daughter, but Silla refused because she was already married. A year later, the Wa formally severed ties, and the year after that the Wa suddenly showed up at Pungdo Island, where they plundered the households and then advanced inland. They surrounded the capital of Gyeongju and quickly attacked. The King of Silla wanted to sally forth with his troops, but his ministers cautioned against it, instead suggesting that they wait out the siege. Sure enough, the Wa supply lines were too long, and they ran out of provisions, causing the Wa to leave. This was in the year 346, so plausibly within the historical period.

There are other attacks, such as the ones in 364 and 393, but we’ll go over those in time. For now I want to focus on these entries in the Silla Annals not because I necessarily believe them in their entirety—I certainly am not ready to give credence to their dates—but I think it definitely demonstrates that by the latter part of the fourth century we see that there is a history between the peninsula and the Wa—and I think it is fair to assume that this includes the Wa on the archipelago.

The first thing that pops out is that there is no mention of actual submission by Silla, but there are moments where they send envoys to broker peace. It is important to remember that Silla would eventually unify the peninsula and so successive dynasties would likely not want to write down any indication of Silla as a subjugated state. And it is unlikely, in my opinion, that they ever were, completely.

The analogy that actually springs to mind for me is that of the British Isles during the raids of the Norsemen—commonly referred to as Vikings, or, more specifically, “going Viking”, aka going on a raid. I see a lot of similarities with a group of able seamen and warriors who could apparently raid and plunder the eastern coast of the peninsula more or less with abandon. There are fewer examples, however, of the Wa rounding the south and west coasts—possibly because the naval forces of the ethnic Han peoples in the south would not have countenanced such piracy, and the Wa were probably keen to stay on the good side of the commanderies, at least until they fell in the early 4th century.

Also like the Norse raiders along the coasts of England, Ireland, and Scotland, I suspect, that the ships the Wa sailed in were not just built for the sea, but could likely be rowed upstream through the various river systems to deploy troops deep inside Silla territory. This is based on the examples we have from haniwa and a handful of other depictions. That could account for how the Wa were getting all the way to the Silla capital, and could also explain the note in the Chronicles about them getting “halfway into the country” quickly and rapidly.

Furthermore, like with the Viking raids against England, the Wa seem to have excelled on the sea. This is unsurprising for people living largely on and amongst islands, whereas Silla and others were probably more practiced fighting on land.

And, one more possible similarity with the Viking raids on England—it is possible that Silla ended up buying them off. This isn’t exactly mentioned anywhere, but it could explain the two different views of the situation. From the Wa standpoint, they really want the goods—which, in the case of the chronicles, they frame as “tribute” being paid to them. However, it isn’t as if Silla were truly under their thumb once they departed, and there is no indication that there was any kind of actual control exerted on the peninsula beyond this desire for tribute-slash-bribery, but that is contextualized in the language of Empire—the language of the Sinitic chronicles that are their template for how such stories are supposed to go.

It may be the case that warriors from Yamato were trading with the peninsula, and when they felt they couldn’t get what they wanted that way, they may have used violence to take things that they felt they needed. This may have even led to forms of payment from peninsular groups and attempts to ally, such as through the traditional practice of marriage alliances that were so prevalent on the archipelago.

Because of all this, I have no problem believing that there was a sovereign—perhaps a female sovereign—who rallied the troops of Yamato and various other provinces and led them on a raid against the continental kingdom of Silla. This probably wasn’t the first such expedition, and it wouldn’t be the last. They may have even had practice raiding various coastal settlements in ways that just never made it into any histories, oral or otherwise. Riding across the waves in their boats, using their paddles to pull them across the straits, they skirted the coastline, possibly picking up others for their raiding party. Eventually they made their way upriver and inland, likely pillaging as they went, and eventually arriving at the Silla capital of Gyeongju. There they may have fought, or it may have been a siege or similar standoff between the various sides. Eventually, the King of Silla may have even met with them under a white flag and offered to send some sort of payment if they would leave. They were likely speaking different languages, and so any negotiations would have required interpreters, and, just as often happens today, the terms of any negotiation may have been conveyed slightly differently in each language. I can imagine a proud Tarashi Hime and Takechi no Sukune returning to their forces probably with some amount of treasure and claiming victory over Silla. I can see the King of Silla spinning the retreat of the Wa forces as a victory in their own right. Each confident that they had come out the victor—or at least that’s how they would make sure it was remembered, at least.

But what about Baekje and Goguryeo? It seems obvious that this was really just between Yamato and Silla at this point. We’ll get to Baekje, shortly, and Goguryeo some time after that, but at this point in the story, we are mostly talking about Silla and Yamato.

There is one more item from the Chronicles that I admittedly skipped over, but I think it would be relevant, here, and these are in some of those “other sources say…” kind of comments that pepper the Nihon Shoki, especially in the more mythical chapters that likely started as purely oral tradition. This has to do with the story of Prince Uro. There are two of these “other sources” stories I’m going to talk about, and then I’ll discuss the parallels we see in the Korean sources.

The first variant from the Nihon Shoki says that the person whom Okinaga Tarashi Hime met was a Prince by the name of Urusoborichiu, who submitted to the Yamato forces, whom some suspect may be a reference to the story of Uro, whose rank in modern Korean reads as “Seoburhan” or “Seopulya”. Could Uru-Soboritiu be the same as Uro Seoburhan?

The second variant doesn’t give the Prince a name, but expands on the story a lot more. In this telling, Tarashi Hime captured a Silla Prince and she had his kneecaps removed and had him crawl along the rocks until she finally slew him. She then installed a governor over Silla and headed back to Yamato. Now the wife of the prince cajoled the governor into telling her where her husband, the Prince, had been buried. Once he told her, she exhumed the body and raised up the people and killed the governor. When Tarashi Hime heard of all of this she was especially wroth and raised another army to punish Silla. The people, afraid of what that would mean, killed the late Prince’s wife to appease Tarashi Hime’s anger.

Again, I wouldn’t exactly take this story at face value for a variety of reasons, but there is some interesting correlation with the Korean records, specifically some events that are described as happening around the year 249. At this point, it’s doubtful that Silla and Baekje even existed as anything other than small parts of the larger confederacies, but we’ve already talked about how time is somewhat flexible in these retellings. So these events could have happened much later, and it could also be the case that the Japanese Chroniclers had access to these records from Silla and Baekje and were inserting the stories they thought were best to bolster the tale of Tarashi Hime.

So, here’s how the Korean records talk about this situation. It turns out there was a Prince named Uro listed in the Silla Annals. He is at one point referenced as the Crown Prince, and helped lead soldiers of the Six Districts of Silla to aid Kara. Despite being named as Crown Prince, he never actually seems to have attained the throne, but he did become a general and had other military successes and became the chief minister of military affairs in Silla by 244. A year later, however, he led troops on an unsuccessful raid against Goguryeo, where the Silla troops had to withdraw to a defense barricade at Madu.

Now it seems in this time there were at least semi-amicable relations between Silla and Yamato, because the Tonggam has an account in 249 of a Wa ambassador named “Kalyako”—possibly Katsuraki no So tsu Hiko, or someone similar. The King asked Prince Uro to entertain this ambassador, and at one point Uro mockingly told the ambassador that “sooner or later we shall make your King our salt-slave and your Queen our cook-wench.” As soon as this got back to the King of Wa, he was understandably upset and he sent an army to invade Silla. The King of Silla retreated to Yuchhon, while Prince Uro made his way to the invading Wa forces to apologize. Apparently words were not enough, and so the men of Wa seized Prince Uro and burned him on a pile of firewood and then left.

Later, another ambassador was sent to Silla. This time, the wife of the late Prince Uro asked to be allowed to entertain him. She got the ambassador away from his retinue, got him quite drunk, and when he was senseless she seized him and burnt him in the same manner that the Wa had burnt her husband. The Wa again attacked and besieged the Silla capital at Gyeongju, but they were unsuccessful.

Now, as with the other parts of this story, we can see how the Silla and Yamato accounts have some similarities, including names of the Prince and others involved, and various other details, such as the story of the wife taking revenge. In Yamato they conflate an ambassador or envoy with a governor, and they don’t mention the outcome of the retaliatory strike. I tend to put a little more faith in the Silla account, as it seems rather believable, but I suspect that the date of 249 CE is probably much earlier than any such event actually happened.

By the way, the Silla Annals in the Samguk Sagi, from which we get some of Prince Uro’s earlier life, also mentions the fateful year of 249, but without much embellishment. All it really gives us is that the Wa killed Seoburhan Uro, presumably in battle, but nothing more is given. It is an odd corroboration, if minimal.

For now, I think that gets us through the so-called Conquest of Korea, but don’t worry, there is plenty more fun to be had over the next episodes. We’ll see an alliance with Baekje and then we’ll continue to address the events on the Gwangaetto Stele. We’ll also talk about how writing first came to the archipelago. This really is an exciting, if confusing, period in Japanese history.

Next episode, however, we have more pressing concerns, and we’ll talk about Tarashi Hime’s son, Homuda Wake, and the succession crisis that she faced when she returned to the archipelago, focusing our attention briefly back on events in Yamato before again looking outward.

So, until next time, thank you for all of your support. If you like what we are doing, tell your friends and feel free to rate us on iTunes, Spotify, or wherever you listen to podcasts. If you feel the need to do more, and want to help us keep this going, we have information about how you can donate through our KoFi site, kofi.com/sengokudaimyo, or find the link over at our main website, SengokuDaimyo.com/Podcast, where we will have some more discussion on topics from this episode. Questions or comments? Feel free to Tweet at us at @SengokuPodcast, or reach out to our Sengoku Daimyo Facebook page.

That’s all for now. Thank you again, and I’ll see you next episode on Sengoku Daimyo’s Chronicles of Japan.

References

Yōko, I. (2019). Revisiting Tsuda Sōkichi in Postwar Japan: “Misunderstandings” and the Historical Facts of the Kiki. Japan Review, (34), 139-160. Retrieved April 24, 2021, from https://www.jstor.org/stable/26864868

Ō, Yasumaro, & Heldt, G. (2014). The Kojiki: An account of ancient matters. ISBN978-0-231-16389-7

Yoshie, A., Tonomura, H., & Takata, A.A. (2013). Gendered Interpretations of Female Rule: The Case of Himiko, Ruler of Yamatai. U.S.-Japan Women's Journal 44, 3-23. doi:10.1353/jwj.2013.0009.

Barnes, G. (2006). Women in the "Nihon Shoki" (4 parts). Durham East Asia Papers, No. 20.

Bentley, John. (2006). The Authenticity of Sendai Kuji Hongi: a New Examination of Texts, with a Translation and Commentary. ISBN-90-04-152253

Lee, Jaehoon (2004). The Relatedness Between the Origin of Japanese and Korean Ethnicity. Florida State Univeristy Libraries, Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations. https://fsu.digital.flvc.org/islandora/object/fsu:181538/datastream/PDF/download/citation.pdf

Allen, C. (2003). Empress Jingū: a shamaness ruler in early Japan. Japan Forum, 15(1), 81–98. https://doi.org/10.1080/0955580032000077748

Allen, C. T. (2003). Prince Misahun: Silla's Hostage to Wa from the Late Fourth Century. Korean Studies, 27(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1353/KS.2005.0002

Philippi, D. L. (1968). Kojiki. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press. ISBN4-13-087004-1

Edwards, W. (1983). Event and Process in the Founding of Japan: The Horserider Theory in Archeological Perspective. Journal of Japanese Studies, 9(2), 265-295. doi:10.2307/132294

Chamberlain, B. H. (1981). The Kojiki: Records of ancient matters. Rutland, Vt: C.E. Tuttle Co. ISBN4-8053-0794-3

Ledyard, G. (1975). Galloping along with the Horseriders: Looking for the Founders of Japan. Journal of Japanese Studies, 1(2), 217-254. doi:10.2307/132125

Aston, W. G. (1972). Nihongi, chronicles of Japan from the earliest times to A.D. 697. London: Allen & Unwin. ISBN0-80480984-4